In Photos: Exploring the Mysterious Plain of Jars Site

Excavating the site

The contents of the ceramic jars excavated from the site will also be carefully examined to confirm if, as the researchers suspect, they hold human remains.

DNA samples

Archaeologists Louise Shewan, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia (center), and Dougald O’Reilly, from Australian National University in Canberra (right), are directing a major five-year investigation of the Plain of Jars site. This photograph shows the researchers removing human teeth from the underside of one of the sandstone disks used to mark some of the ancient graves at Jar Site 1.

Genetic material from the ancient teeth with be used for DNA analysis, while traces of radioactive strontium will be used to identify the geological signature of the area where the people buried here gathered their food.

Eyes in the sky

The researchers also used aerial drones, like this one, over Jar Site 1 to map the unique landscape of the Plain of Jars to build a virtual reality simulation of the area and to aid ongoing archaeological research.

Aerial footage

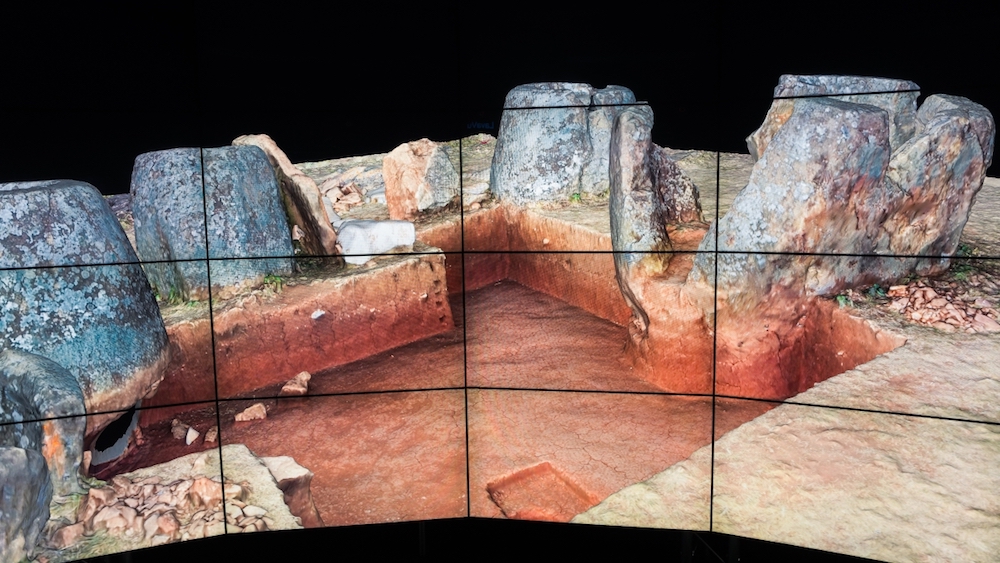

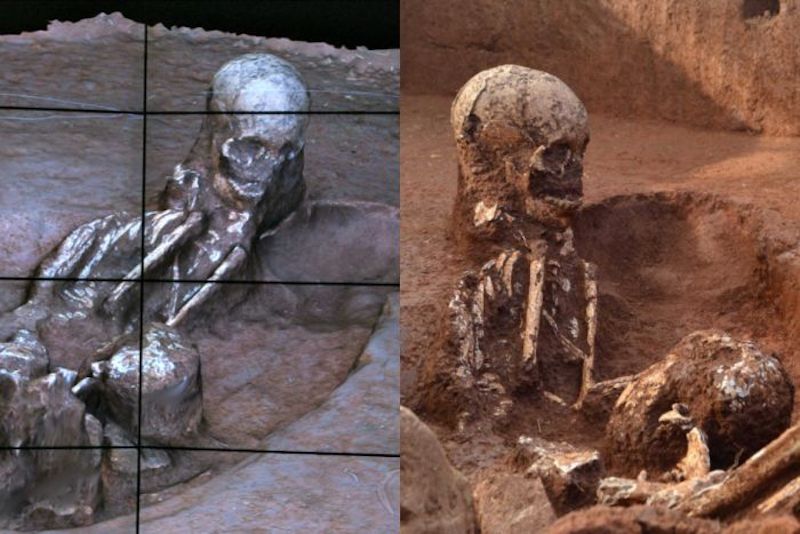

Aerial footage from the drones has been combined with data from geophysical surveys and ground-penetrating radar to create a 3D virtual replica of Site 1 at the Plain of Jars. The simulation will enable researchers to review and explore the site from the advanced Cave2 virtual reality facility at Monash University in Australia.

Immersive experience

The aerial landscape images and other data from research at the Plain of Jars have been integrated into an advanced 3D simulation at the Cave2 virtual reality facility at Monash University. The simulation lets researchers in Australia view and explore the images and other data from the different research efforts within the Plain of Jars Archeological Project.

Digital records

The Cave2 simulation also records a timeline that can be stepped forward or back to show the state of the excavations at any time, and which will be updated as the digs and discoveries at the Plain of Jars continue at Site 1 and other jar sites in the years to come.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Seeing through the trees

Aerial drones will also be used to map jar sites that are too rugged for traditional archaeological methods, such as Jar Site 52, shown here, which is in broken country covered by trees and bush.

Drones also let the researchers explore some of the many jar sites where undetonated cluster bombs left over from the bombardment of Laos during the Vietnam War make it too dangerous to dig.

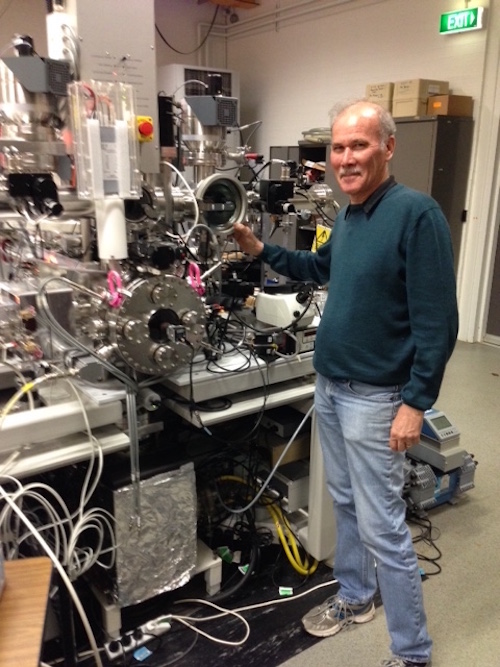

Origin of the stones

Richard Armstrong, an archaeologist and geochemist at Australian National University, is leading research to learn more about the origins of the stone jars themselves, using uranium-lead dating on traces of the mineral zircon in the rocks the jars were quarried from. This information will give accurate ages for the stone jars, and help to date the quarries where they were made.

Recording history

The researchers say the virtual simulation of the Plain of Jars will serve as a digital record of scholarship about the Plain of Jars as their investigations continue. It will also be used to support the designation of the Plain of Jars as a UNESCO World Heritage site, which the Laos government hopes will stimulate tourism and further scientific research in the region.

Scattered with jars

When Laos and Australian scientists returned to the Xiangkhouang region in 2019, they carried out excavations around some of the stone jars at what is known as Site 2. The jar site, about 10 miles (15 km) south of the town of Phonsavan, contains more than 90 ancient carved stone jars.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.