Jeepers, Peepers! Tully Monster's Eyes Prove It's a Vertebrate

A tiny clue hidden in the bizarre eyes of the 300-million-year-old remains of a "Tully monster" has helped scientists determine that the curious creature is a vertebrate, a new study finds.

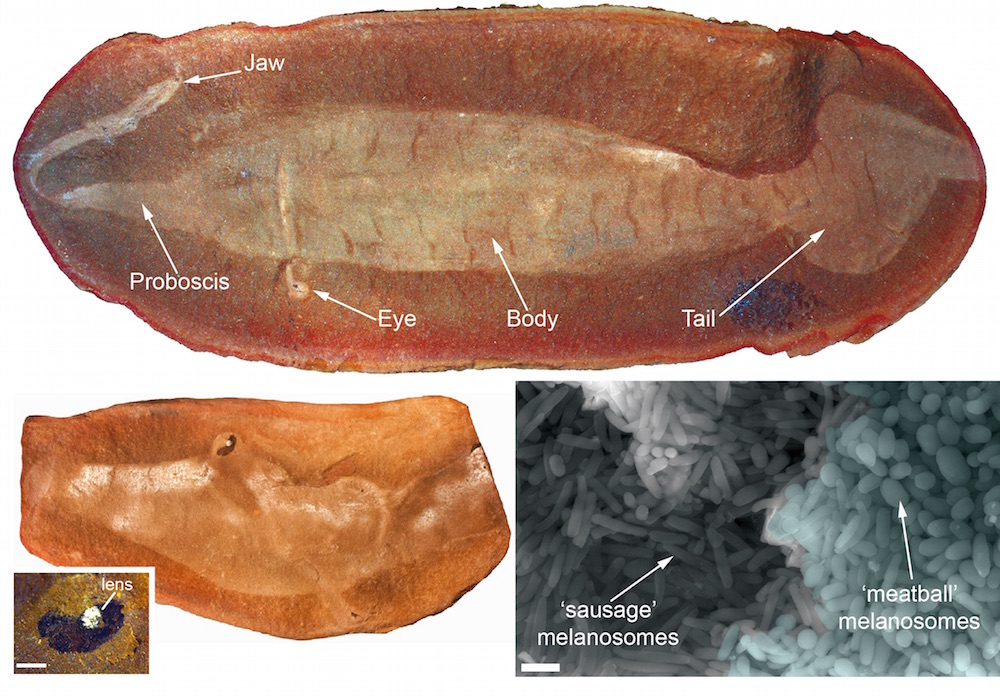

Researchers analyzed the so-called monster's eyes, and found that they held two different kinds of pigment cells. Some of these cells looked like microscopic sausages, and the others looked like tiny meatballs, the researchers said.

Only vertebrates have these pigment cells that resemble sausages and meatballs, indicating that Tully (Tullimonstrum gregarium) wasn't an invertebrate, but rather had a backbone, they said. [Photos: Ancient Tully Monster's Identity Revealed]

"This is an exciting study because not [only] have we discovered the oldest fossil pigment, but the structures seen in Tullimonstrum's eyes suggest it had good vision," the study's lead researcher Thomas Clements, a doctoral student in the Department of Geology at the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom, said in a statement. "The large tail and teeth suggest that the Tully Monster is, in fact, a type of very weird fish."

The Tully monster has a storied history. Amateur fossil collector Francis Tully discovered the first fossil of the monster in 1958. Since then, so many Tully monster fossils have been uncovered in Illinois' coal quarries, that the state made it the official state fossil.

Even so, scientists couldn't figure out what type of creature the fossils represented.

Since the Tully monster's discovery over 60 years ago, "scientists have suggested it is a whole parade of completely different creatures, ranging from mollusks to worms," said study senior researcher Sarah Gabbott, a professor in the Department of Geology at the University of Leicester. "But there was no conclusive evidence, and so speculation continued."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new study, the researchers focused on the creature's blobby eyes — round balls that sat at the ends of hammerhead-like eyestalks. These dark blobs were composed of hundreds of thousands of microscopic dark granules, they found. Each granule was tiny, about 50 times smaller than the width of a human hair, they said.

The granules' shape and chemical makeup suggested that they were organelles found within melanosomes, cells that create and store the pigment melanin, the researchers said.

"We used a new technique called Time of Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) to identify the chemical signature of the fossil granules, and compared it to known modern melanin from crows," said study co-researcher Jakob Vinther, a senior lecturer of macroevolution at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom. "This proved that we had discovered the oldest fossil pigment currently known."

Most animals produce the pigment melanin, which gives people their skin and hair color.

"Melanin is also found in the eyes of many animal groups, where it stops light from bouncing around inside the eyeball and allows the formation of a clear visual image," Clements said. "This is the first unequivocal evidence that Tullimonstrum is a member of the same group of animals as us, the vertebrates." [Photos: Ancient Fish Had Well-Developed Lung]

This is the second Tully monster study published this spring. The first study, detailed in the journal Nature by a different group of researchers, characterized the monster as an ancient jawless fish. Before reaching that conclusion, they examined more than 1,200 Tully monster fossils before describing it as a weird, Dr. Seuss-like creature.

The new study reaches many of the same conclusions.

"Perhaps even weirder fossil vertebrates remain to be dug up," Shigeru Kuratani and Tatsuya Hirasawa, researchers at the Evolutionary Morphology Laboratory at RIKEN, one of Japan's largest research institutions, wrote in a commentary, also published in the journal Nature.

The study was published online today (April 13) in the journal Nature.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.