A trove of shackled skeletons unearthed in a mass grave near Athens may have once belonged to the followers of a tyrant who sought to overthrow the leader of ancient Greece.

"These might be the remains of people who were part of this coup in Athens in 632 [B.C.], the Coup of Cylon," said Kristina Killgrove, a bioarchaeologist at the University of West Florida, in Pensacola, who was not involved in the current study.

Ancient burial complex

The mass grave was uncovered as archaeologists were excavating a huge cemetery in the ancient port city of Phaleron, just 4 miles (6.4 kilometers) from Athens. Over the last several years, archaeologists led by Stella Chrysoulaki, of Greece's Department of Antiquities of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, have unearthed a huge complex filled with ancient skeletons dating to between the eighth and fifth centuries B.C. [8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

Some of the graves at Phaleron, including those of shackled individuals, have been known for about a century, but in the last four years, newer excavations have uncovered a huge trove of additional bodies. All told, the burial site is about 1 acre (4,046 square meters) in area and holds at least 1,500 skeletons.

"This is just a massive number of burials, which is absolutely fantastic," Killgrove told Live Science.

Doomed to die

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Among the skeletons found were a group of about 80 people who were lined up in the mass grave, with 36 whose hands were bound with iron shackles, according to the Greek Ministry of Culture.

A few pieces of pottery found near the skeletons suggest that these ancient prisoners died between 650 B.C. and 625 B.C., the Greek Ministry of Culture said in a statement.

That date could tie the prisoners to an ancient coup. In 632 B.C., the former Olympic champion Cylon tried to take over the Acropolis in Athens. His revolt was put down, and though Cylon may have escaped, his followers were put to death, after an initial promise to let them live was broken, according to "The Date of Cylon: A Study in Early Athenian History" (Harvard University Press, 1982).

However, it's not certain these ancient prisoners are in any way connected to Cylon, Killgrove said.

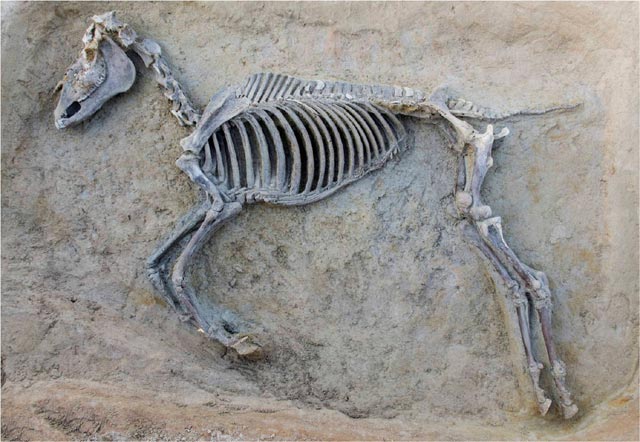

Other skeletons at the site were buried in jars, in open pits, or in funeral pyres. The site even contains a horse burial, the researchers said.

While the backstory of these doomed prisoners is fascinating, the site is also unique because of what it may reveal about the lives of the average Joe (or "Ioseph"?) in the centuries before the golden age of the Greek city-states, between the fifth and the third centuries B.C., Killgrove said.

"We don't have information about people who aren't in historical records," Killgrove said. "Learning more about the lower social classes in Athens tells us a lot about the rise of the city-state in Athens."

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.