Small-Brained Titanosaur Had Super Senses

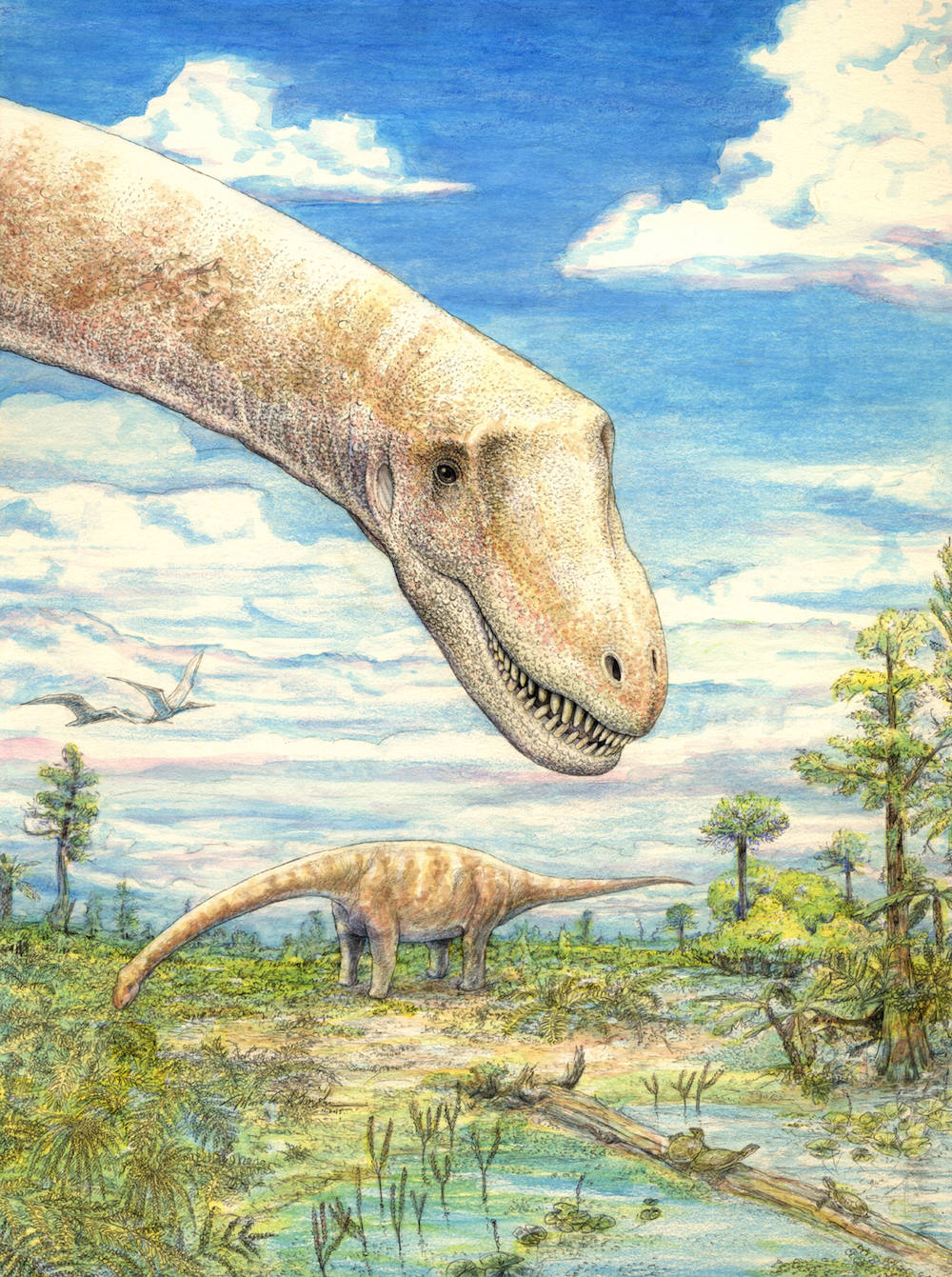

The teeny-tiny head of a ginormous, long-necked titanosaur is revealing secrets about the massive, 95-million-year-old paleo beast, a new study finds.

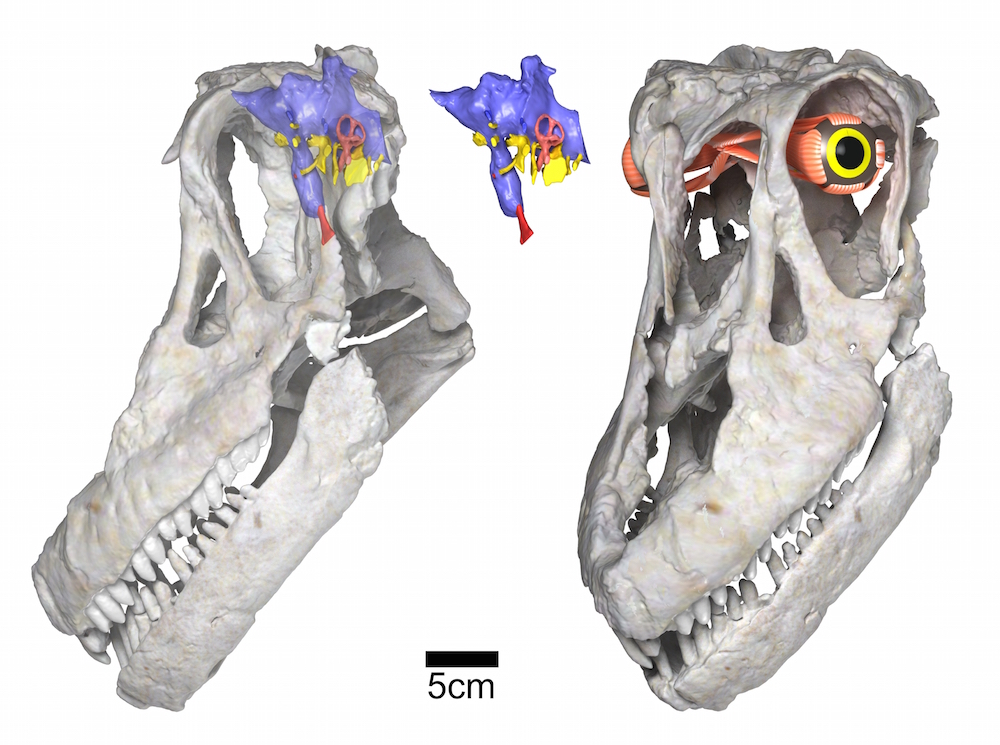

Despite its small brain, the titanosaur had well-developed senses, the researchers found. The giant dinosaur had large eye sockets, suggesting it had big eyes and good vision to help it find food and mates and to avoid predators, they said. It also had an inner ear attuned to detecting low-frequency sounds, likely those made by other titanosaurs, they said.

Moreover, the balance organ in its inner ear suggests that the dinosaur's head and snout regularly faced downward, indicating that it fed on low-growing plants, the researchers said. [See Images of the Rare Titanosaur Skull]

Titanosaurs are the most massive land animals ever to have existed on Earth, but finding their heads is extremely rare. In fact, of the 60 known groups of titanosaur that lived during the Cretaceous period, only three have skulls that have been discovered: Nemegtosaurus mongoliensis in Mongolia, Rapetosaurus krausei in Madagascar, and Tapuiasaurus macedoi in Brazil, the researchers said.

"Our understanding of the animal has been really hampered by its headlessness," said study co-author Matthew Lamanna, the assistant curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh.

It's not clear why titanosaurs lose their heads after death, but Lamanna shared one theory.

"When you've got a river system, or any kind of environment where the water is moving quickly enough to transport enough sediment to bury one of these behemoths in time for it to be relatively well preserved, oftentimes, currents of that magnitude are probably going to wash away pretty small and delicate structures, such as heads," he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

That's what makes this finding so valuable, he added.

"You don't get rarer [finds] than sauropod skulls," Lamanna told Live Science. "They're among the rarest of any kind of dinosaur fossil."

Patagonia discovery

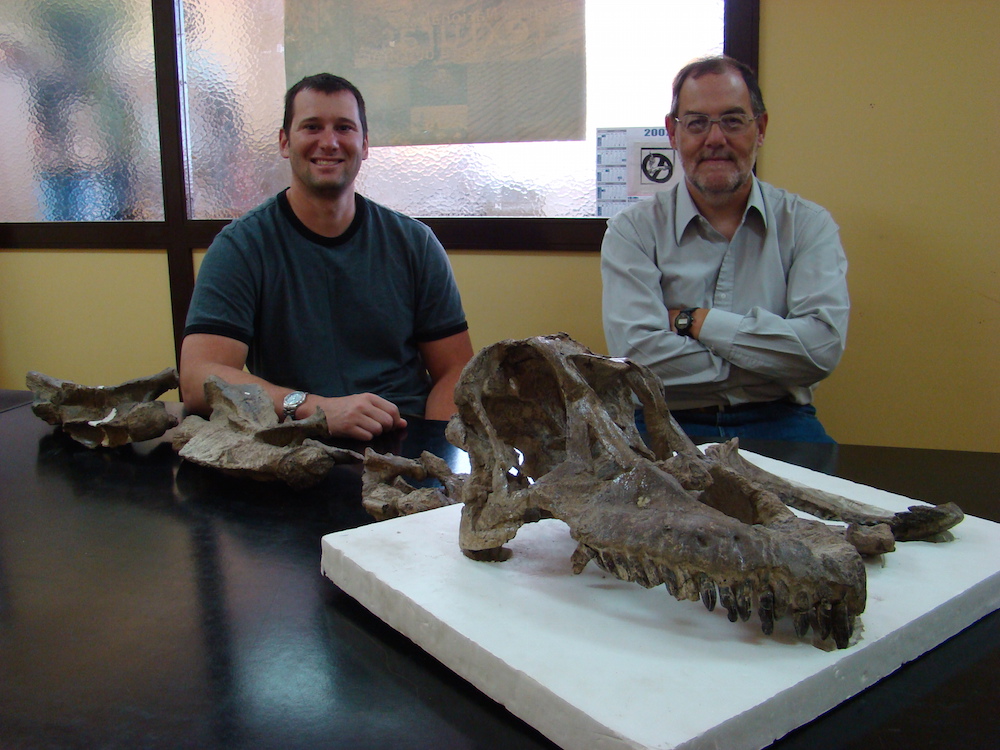

Rubén Martínez, the study's lead author and the director of the paleo-vertebrate lab at the National University of Patagonia San Juan Bosco in Argentina, discovered the newfound skull and several neck vertebrae in central Patagonia in 1997. The finding was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, but he and his colleagues didn't have time to study it until now, Martínez said.

They got down to business soon enough, naming the previously unknown species Sarmientosaurus musacchioi. The genus name honors the Patagonian town of Sarmiento, where they found the titanosaur. The species name is a tribute to the late Eduardo Musacchio, a paleontologist and educator at the National University of Patagonia San Juan Bosco.

The 17-inch-long (43 centimeters) skull is arguably one of the most complete titanosaur skulls on record, the researchers said. They analyzed the fossils and ran them through a computed tomographic (CT) scanner to get a better picture of the skull's structures, including the brain case and inner ear.

"The Sarmientosaurus skull is beautifully preserved, which meant that we could tease out a ton of information," study senior author Lawrence Witmer, an expert on cranial anatomy at Ohio University, said in a statement. [Photos: Giant Sauropods Plodded Along in Scottish Lagoon]

For instance, S. musacchioi lived much more recently than the Brazilian T. macedoi, which plodded Earth during the Aptian age (125 million to 113 million years ago). But surprisingly, S. musacchioi's skull and teeth are more primitive — that is, less developed — than those of its Brazilian cousin, the researchers said. This suggests that titanosaurs with extremely different cranial and dental structures coexisted during the Cretaceous, they said.

CT scans showed that the newly identified titanosaur had hollow neck vertebrae, just like modern birds do today, Martínez told Live Science. The researchers also found a bony tendon within the S. musacchioi specimen, making it the first nonavian dinosaur to have this bizarre structure, whose function is unknown, he said.

It's difficult to estimate the dinosaur's size based on just its skull, but by comparing it to its relative T. macedoi, the researchers calculated that S. musacchioi was about 40 feet (12 meters) long and weighed about 10 tons (9 metric tons), or about as much as two elephants, Lamanna said.

Although the fossils will remain in Argentina, people can get a glimpse of a 3D-printed replica of the titanosaur's skull and reconstructed brain at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History within the next few days, Lamanna said.

The study was published online today (April 26) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.