In Photos: Glow-in-the-Dark Sharks

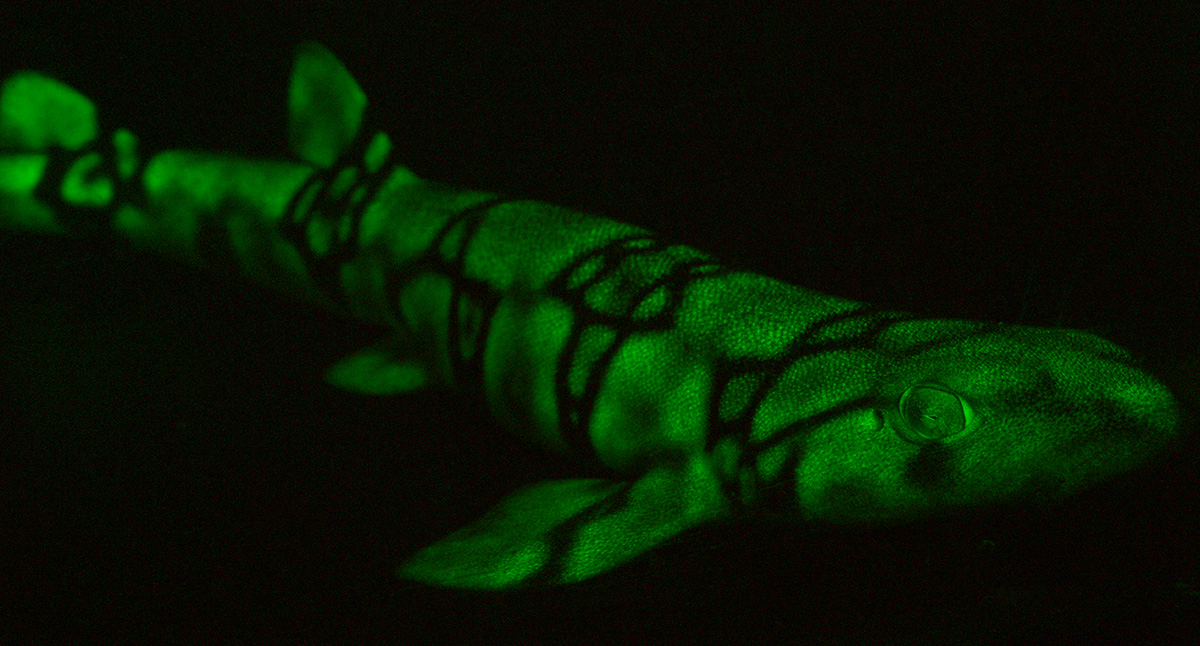

Glow-in-the-Dark Shark

A biofluorescent chain catshark (Scyliorhinus rotifer), one of two sharks known to biofluoresce. Special proteins in this shark's skin absorb blue light — the only light that penetrates to depth in the ocean — and transform it to a shorter wavelength, resulting in green coloration.

New research published in Scientific Reports finds that sharks can see this fluorescence and that the coloration makes them more visible in the dark blue light of the ocean. Researchers have yet to learn if the sharks use the color to communicate or how. Here's a look at the amazing sharks and their glowing patterns.

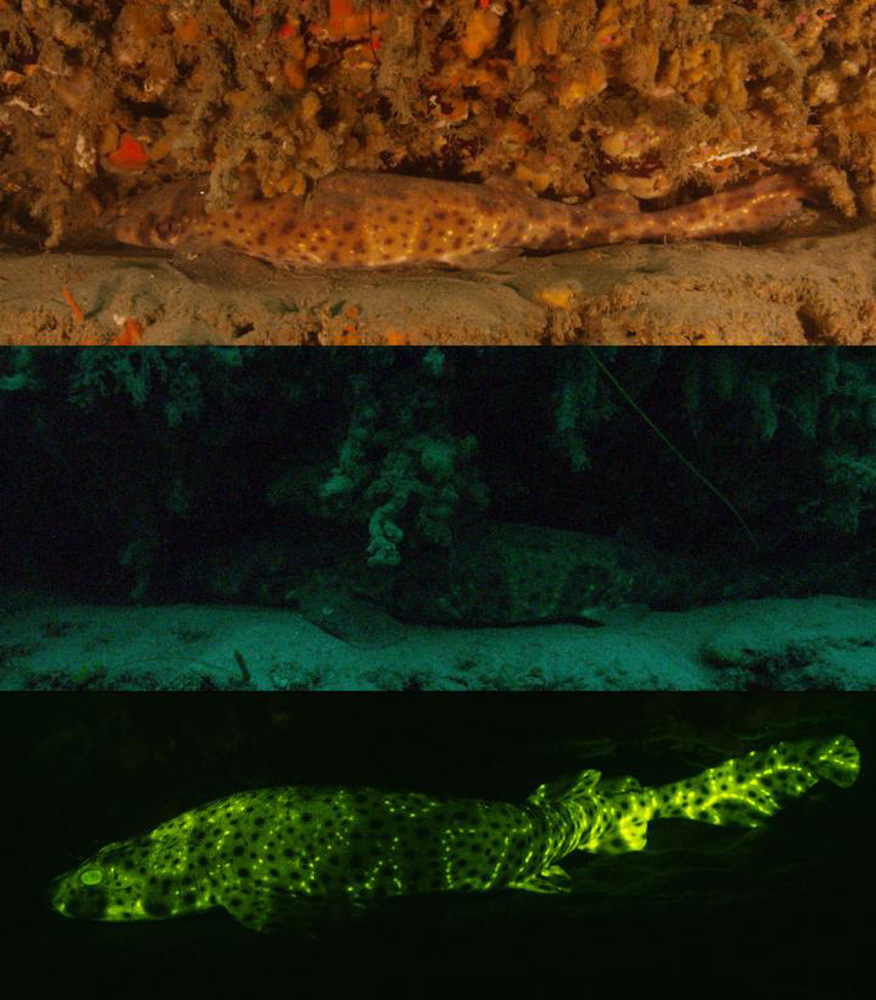

Tricolor Shark

A swellshark (Cephaloscyllium ventriosum) is about 3 feet (1 meter) long and gets its name because when threatened, it can gulp water to swell in size. Now, researchers have found that swellsharks are biofluorescent. This image shows the sharks under white light (top), natural light (middle) and blue light (bottom). The blue-light image represents the kind of light that penetrates into the shark's range, which starts at about 80 feet (24 meters) below the surface. Red light vanishes from the marine environment at only 32 feet (10 m).

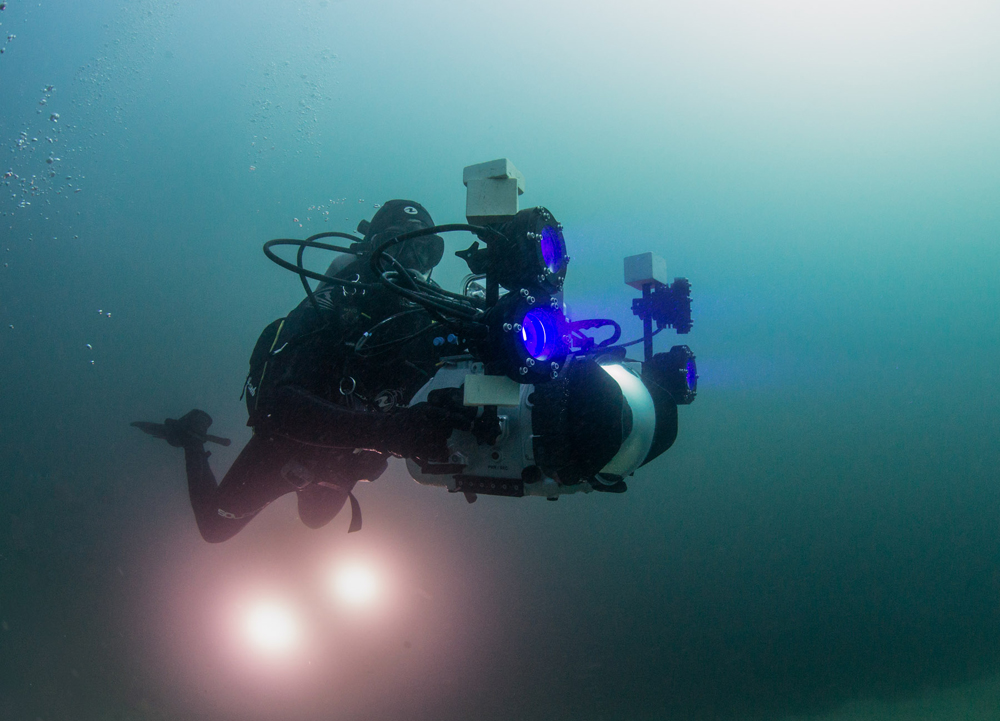

Blue Light

Gruber and his colleagues were excited to find biofluorescent sharks and fish because those animals have advanced vision that might allow them to signal and communicate with their fluorescent abilities. To find out if sharks could really see their own skin fluorescence, the researchers analyzed the sharks' eye receptors and used that information to build a shark-eye camera that sees the world much like sharks do. They then swam with this camera to determine what biofluorescence looks like in a natural environment to these animals.

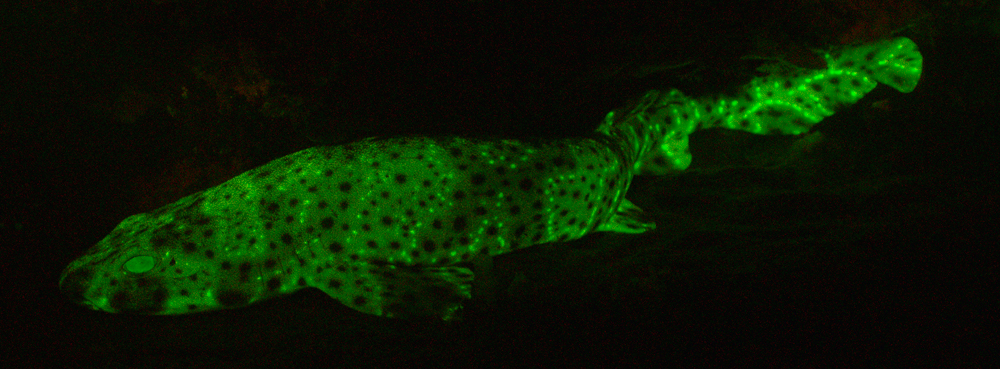

Swell Shark

A biofluorescent swellshark under blue light has a "twinkling" pattern, Gruber told Live Science. The green coloration increases the contrast of the sharks against their dark blue ocean background. A computer model suggests that the deeper the shark dives, the more pronounced this contrast becomes.

Invisible colors

A biofluorescent swellshark. Preliminary analysis suggests that male and female sharks may have different patterns of biofluorescence, opening up the possibility that these patterns are used for signaling or identification. Researchers have yet to delve into the behavioral implications of the discovery of biofluorescence in sharks and other fish. Even sea turtles have been shown to biofluoresce.

Swimming like a shark

Marine biologist David Gruber and his team dive with a "shark-eye camera" to get a sense of how catsharks see the world. Biofluorescence is widespread in fish and has even been seen in sea turtles, Gruber and his colleagues reported in 2014. The phenomenon occurs in the low-light conditions above 3,280 feet (1,000 meters) in the ocean, Gruber said in a TED Talk on the subject. Below that level, animals often create their own light using bioluminescence. [Read more about the glowing shark study]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Shark-Eye Camera

Marine biologist David Gruber diving with a shark-eye camera that filters light to see as sharks do. Gruber originally studied biofluorescence in corals until the chance discovery of a biofluorescent eel in a coral reef got him interested in fluorescent proteins in fish.

White-light Shark

A swellshark seen under white light, showing the shark's brown-and-beige mottled skin. This view is misleading from the point of view of a shark's ecology: In the blue light of the ocean, sharks see each other as patterned in biofluorescent green.

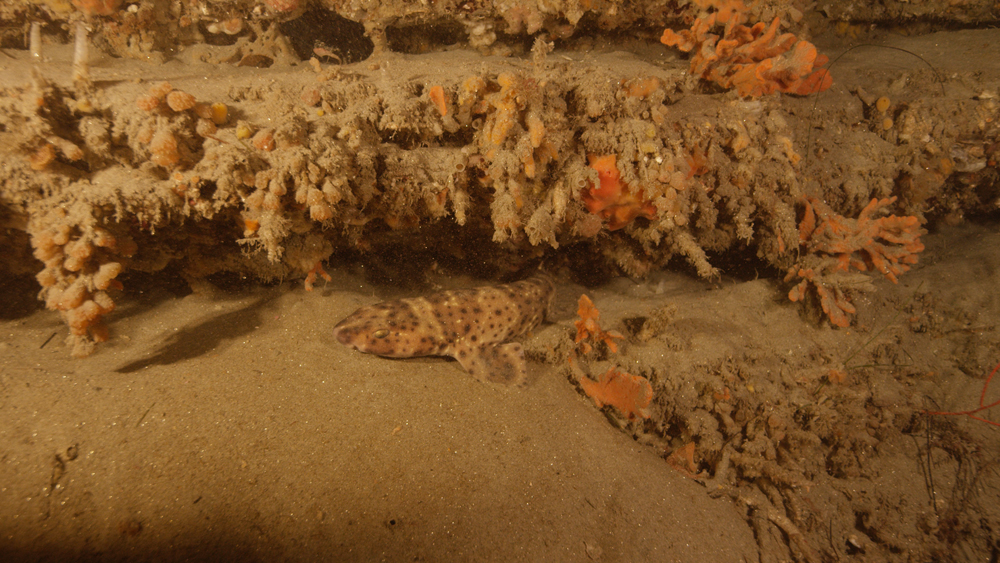

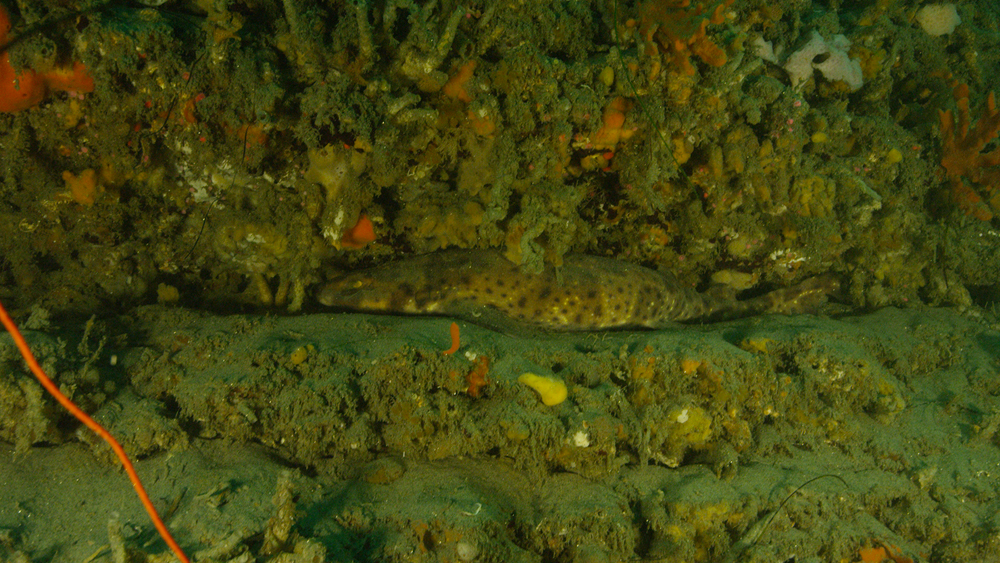

Swell Shark at Home

Swellsharks are one of two species of catshark known to biofluoresce. Called green fluorescent proteins, the proteins that make such fluorescence possible have been used in medical and brain research as markers that "light up" to signal certain biological activities or substances.

Canyon shark

A swellshark under white light in Scripps Canyon off of San Diego, where divers took their shark-eye camera to investigate how catsharks like this swellshark see in the blue light of the ocean. The sharks can see very well in low-light, but don't see in color. Their eyes detect colors on the cusp between blue and green wavelengths, which means they can see each other's green fluorescent skin.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.