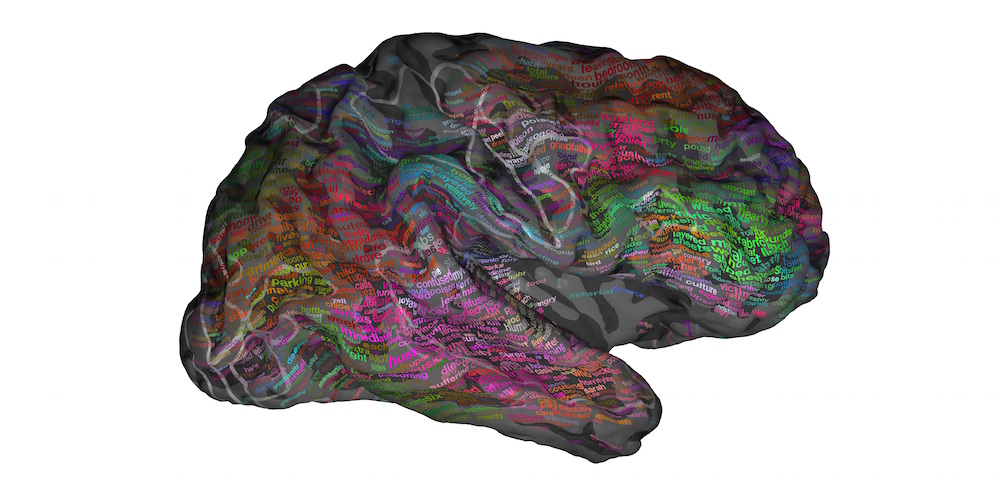

A new brain atlas shows where our noggins store many ideas and words.

Words and concepts are clustered in very specific regions of the cortex, the outer layer of the brain responsible for most higher-order thinking. For instance, some parts of this brain region light up when people are thinking about violence versus social relationships versus conceptions of time.

"Our semantic models are good at predicting responses to language in several big swaths of cortex," study lead author Alex Huth, a postdoctoral researcher in neuroscience at the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement. "But we also get the fine-grained information that tells us what kind of information is represented in each brain area. That's why these maps are so exciting and hold so much potential." [Inside the Brain: A Photo Journey Through Time]

What's more, these mental word maps are fairly consistent across different people, the scientists found.

Mental models

One of the key differences between the human brain and the brains of other animals is its amazing capacity for language. For centuries, scientists have tried to uncover the root of language in the brain, often by looking at what happens when something goes wrong with language processing.

For instance, in the 1800s, the physician Paul Broca analyzed the brain of the mysterious, wordless patient Tan and determined that one particular region, now called Broca's area, was responsible for speaking language. Other studies pinpointed Wernicke's area as another key region for understanding and processing language, and researchers eventually discovered a kind of linguistic highway of nerve cells between the two regions.

But all of those insights didn't come close to explaining how the brain translated abstract thoughts and concepts, feelings, emotions and sensory experience into strings of words and sentences.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Map of language

To get a more detailed understanding of exactly how the brain processes language, Huth and his colleagues studied the brains of six volunteers as they sat utterly still, inside a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine, with their eyes closed, wearing headphones and listening to hours of the public radio show "The Moth Radio Hour." (Huth was also one of the volunteers.)

While the volunteers listened, the MRI machine measured the blood flow in different regions of the brain. This showed which parts of the brain were active during certain parts of the show. Then, the team tied the patterns of blood-flow activity with each sound made in the show at that time.

The researchers combined that information with an algorithm that generated a kind of linguistic map showing how closely connected words are in meaning. (For instance, "hot" and "warm" are more closely related than "hot" and "kittens.")

Using this data, the team was able to recreate a language map of where certain words and concepts were processed in the brain. It turned out that language was represented widely throughout the cortex. The researchers described the map Thursday (April 28) in the journal Nature.

"To be able to map out semantic representations at this level of detail is a stunning accomplishment," Kenneth Whang, a program director in the National Science Foundation's Information and Intelligent Systems division, said in the statement. "In addition, they are showing how data-driven computational methods can help us understand the brain at the level of richness and complexity that we associate with human cognitive processes."

The new findings could one day be used as a kind of mind reading, which could help give voice to the thoughts of people with language impairments, such as people with locked-in syndrome, who cannot move their bodies, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or those who have suffered a stroke.

Still, much more research needs to be done before scientists can use these brain maps to navigate and decode a person's inner monologue.

"Although the maps are broadly consistent across individuals, there are also substantial individual differences," said Jack Gallant, a neuroscientist at the University of California, Berkeley. "We will need to conduct further studies across a larger, more diverse sample of people before we will be able to map these individual differences in detail."

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.