520-Million-Year-Old Fossil Larva Preserved in 3D

If you think finding a needle in a haystack sounds challenging, try searching for fossils the size of fingernail clippings in massive slabs of rock.

But that's just what a team of scientists is doing at a site in Chengjiang, China. And they recently struck a fossil jackpot, discovering an extremely rare arthropod larva fossil measuring a mere 0.08 inches (2 millimeters) long.

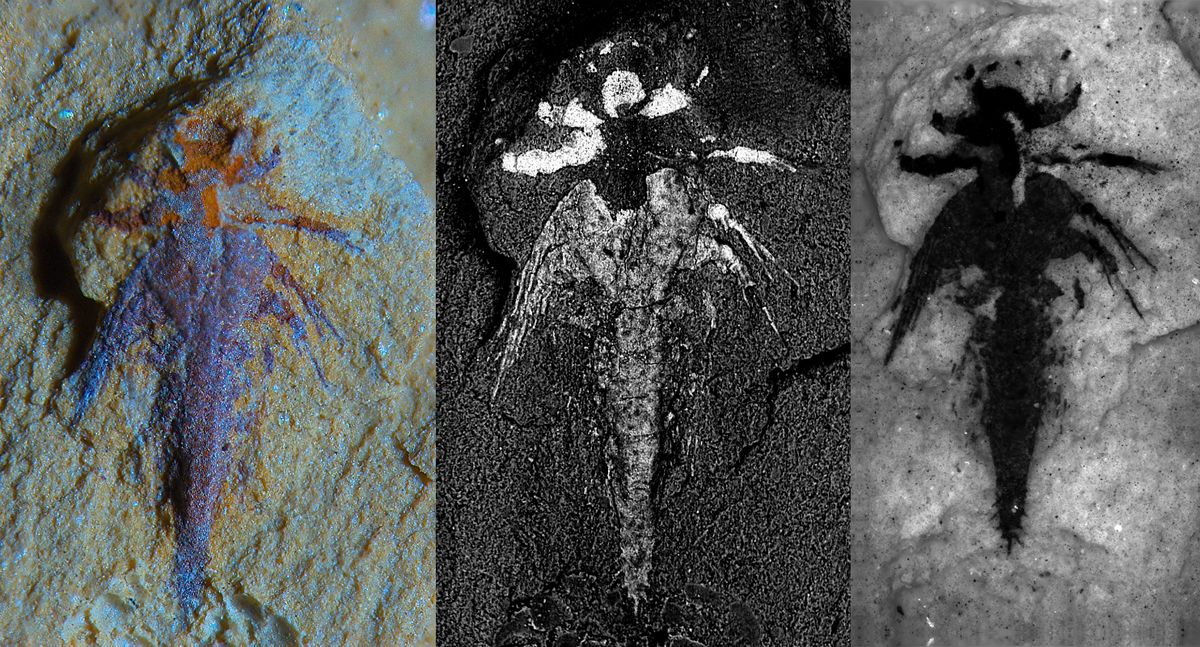

The fossil, estimated to be 520 million years old, was preserved in 3D, presenting the researchers with an exceptional level of detail for this very early stage of the creature's development. It also provided them with a first glimpse of ancestral larval forms in arthropods, the invertebrate animal group with exoskeletons and segmented bodies that includes arachnids, crustaceans and insects. [Photos: A Cambrian Larva With a 'Daggerlike' Tail]

The larva has a segmented body, with two large structures on its head, four pairs of branching legs and three additional pairs of legs that are much less developed. Its posterior is tipped with a "dagger-like" appendage, framed by two triangular forms resembling paddles, which the scientists suggest may have been used for swimming.

This is the first fossil of its kind to be found at Chengjiang since the site's discovery in 1984, according to Yu Liu, the study's lead author and a postdoctoral researcher at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich.

The researchers identified the tiny fossil as a known species — Leanchoilia illecebrosa, a member of the "short great appendage arthropods," which earned their name due to the large claw-like structures attached to their heads, likely used for feeding or for sensing their environment.

In fact, it was the shape of those appendages in the larva fossil that helped the scientists with their identification, Liu told Live Science in an email.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But compared to adult forms, other limbs in the fossil were not as well developed. This told the scientists that the new discovery represented an early larval stage, Liu said.

Hidden in rock

Finding fossils this small is no easy task. It begins with removing large slabs of rock, splitting them into somewhat smaller slabs, and then reviewing them with a magnifying lens to see if there might be "something interesting" preserved in them, according to Liu.

"As you may imagine, the chance of finding a fossil is not very high," Liu told Live Science. "In most cases, you get one fossil after separating tens of slabs. The chance of finding a GOOD fossil is even lower. You need to separate hundreds or even thousands of slabs for that."

Such tiny and delicate specimens like this one can't be isolated from the rocky material around them with the methods traditionally used for chipping out larger fossils. Paleontologists use microphotography and scanning technology rather than picks, drills, or chisels to "penetrate" the rock and show them the remains of once-living animals preserved inside.

3D surprise

And finding such a small fossil preserved in 3D was unexpected and exciting, Liu said. Micro computed tomography — micro-CT scans — of the larva offered a highly detailed picture of its body, with an interesting surprise as a result.

This particular larva's body type — one in which body segments are added as the creature grows to adulthood — was already thought to be typical for modern crustaceans, Liu said. But, finding one this far back in the fossil record hints that this was a feature in all other arthropod ancestors, as well.

This rare find represents an important puzzle piece for investigating the mysteries of the Cambrian radiation — an evolutionary boom period that began about 543 million years ago and lasted around 53 million years — the researchers wrote in their study. Understanding these ancient animals' stages of development could help to unravel the mechanisms that gave rise to the unprecedented diversity of living forms in Earth's distant past.

The findings were published online May 2 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.