More than 100 Tiny Temblors Shake Mount St. Helens

Tiny temblors are shaking Mount St. Helens, indicating that the magma beneath the volcano is on the move, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) reports.

These mini earthquakes, along with the fact that the ground around the volcano is moving ever so slightly away from it, suggest that Mount St. Helens will one day erupt again, said Seth Moran, the scientist in charge at the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory in Vancouver, Washington.

However, this upcoming eruption is likely "years to decades down the road,"Moran told Live Science.

Mount St. Helens, located in the Cascade Mountain range in southern Washington, is known for its enormous eruption on May 18, 1980. The eruption, which was preceded by more than 10,000 earthquakes, killed 57 people, according to USGS. [In Photos: The Incredible 1980 Eruption of Mount St. Helens]

These earthquakes started small, but grew into the 4-magnitude range as the volcano neared its eruption, finally reaching a magnitude 5.1 the morning of May 18, USGS reported.

"What we're looking at [now] is way smaller," Moran said.

Mount St. Helens had a much smaller eruption lasting from 2004 to 2008, USGS said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

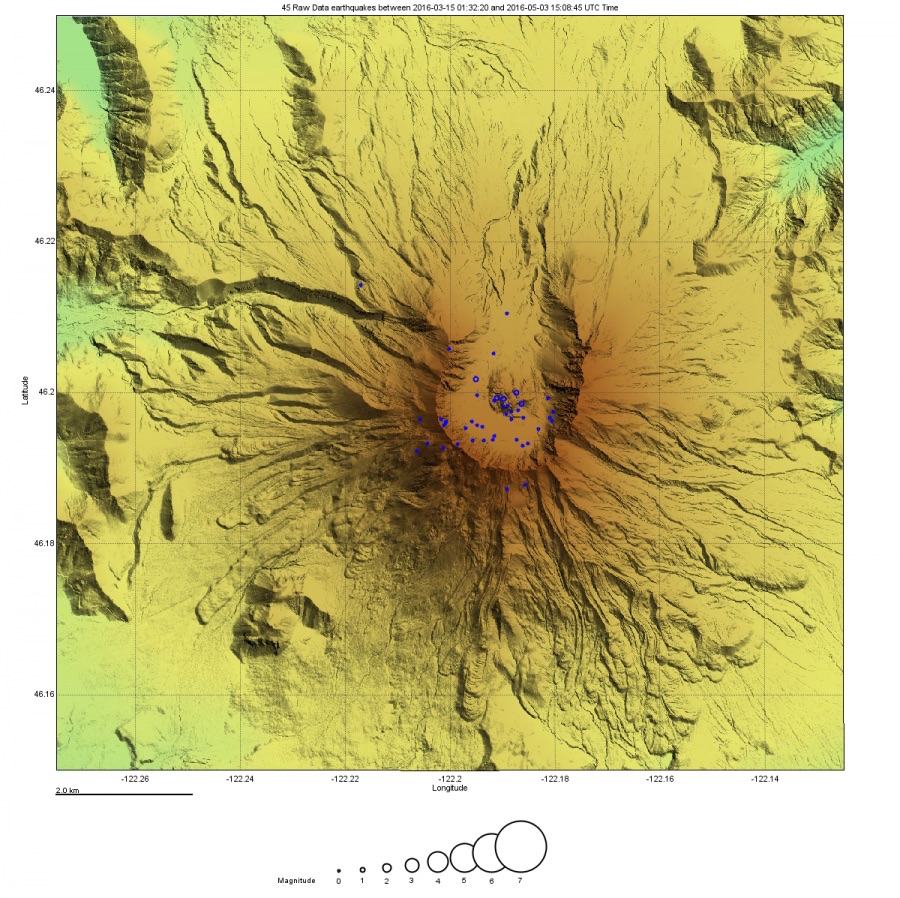

The latest earthquakes — most registering a magnitude of 0.5 or less, with the largest reaching a magnitude 1.3 — started March 14, 2016, at a depth between 1.2 miles and 4 miles (2 and 7 kilometers), USGS said.

During the past eight weeks, researchers have recorded more than 130 of these tiny earthquakes. The rate of the temblors has been increasing since March, reaching almost 40 earthquakes a week, the USGS said.

Moreover, global positioning system (GPS) instruments placed around the volcano show a slight ground movement. Over the past eight years, the ground has moved between 0.4 inches to 0.8 inches (1 to 2 centimeters) away from the volcano, Moran said.

Both of these signs — the earthquakes and the movement — are volcano-tectonic in nature, the USGS said. These signs are probably happening because of a slip on a small fault, the agency said.

"Such events are commonly seen in active hydrothermal and magmatic systems," the USGS said. "The magma chamber is likely imparting its own stresses on the crust around and above it, as the system slowly recharges. The stress drives fluids through cracks, producing the small quakes."

Similar events happened in 2013 and 2014, and in the 1990s a swarm of earthquakes were even more frequent and released more energy, USGS said.

However, the USGS hasn't detected any anomalous gases coming from the volcano, which would suggest magma is pushing up toward the surface. "As was observed at Mount St. Helens between 1987 [and] 2004, recharge can continue for many years beneath a volcano without an eruption," USGS said.

What's more, Mount St. Helens is hardly the only active volcano in the United States. For instance, the Pavlof volcano in Alaska spewed ash 20,000 feet (6,000 meters) into the air in late March, and Hawaii's Kilauea volcano has been continuously erupting since 1983, Moran said.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.