Nefertiti Still Missing: King Tut's Tomb Shows No Hidden Chambers

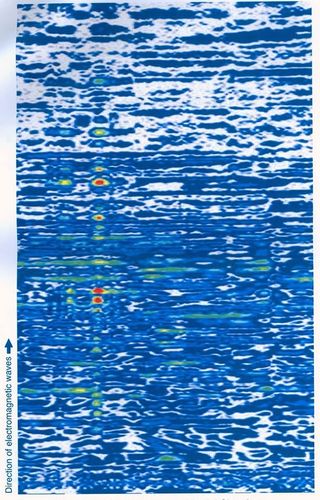

Radar scans conducted by a National Geographic team have found that there are no hidden chambers in Tutankhamun's tomb, disproving a claim that the secret grave of Queen Nefertiti lurks behind the walls.

"If we had a void, we should have a strong reflection," Dean Goodman, a geophysicist at GPR-Slice software told National Geographic News, which published a feature on the research. "But it just doesn't exist."

Live Science contacted Goodman about the research. Goodman said that though he prepared a response, a nondisclosure agreement with the National Geographic Society meant that he needed the society's permission to release that statement. [See Photos of King Tut's Burial and Radar Scans]

The society refused this permission, sending a statement to Live Science this morning (May 10), explaining that the society's agreement with Egypt's antiquities ministry prevents it from granting media access.

Sources contacted by Live Science, however, have confirmed that the scans did not find evidence for a hidden chamber or any sign of Queen Nefertiti's tomb. (Those sources asked to remain anonymous.)

Hyped-up claim

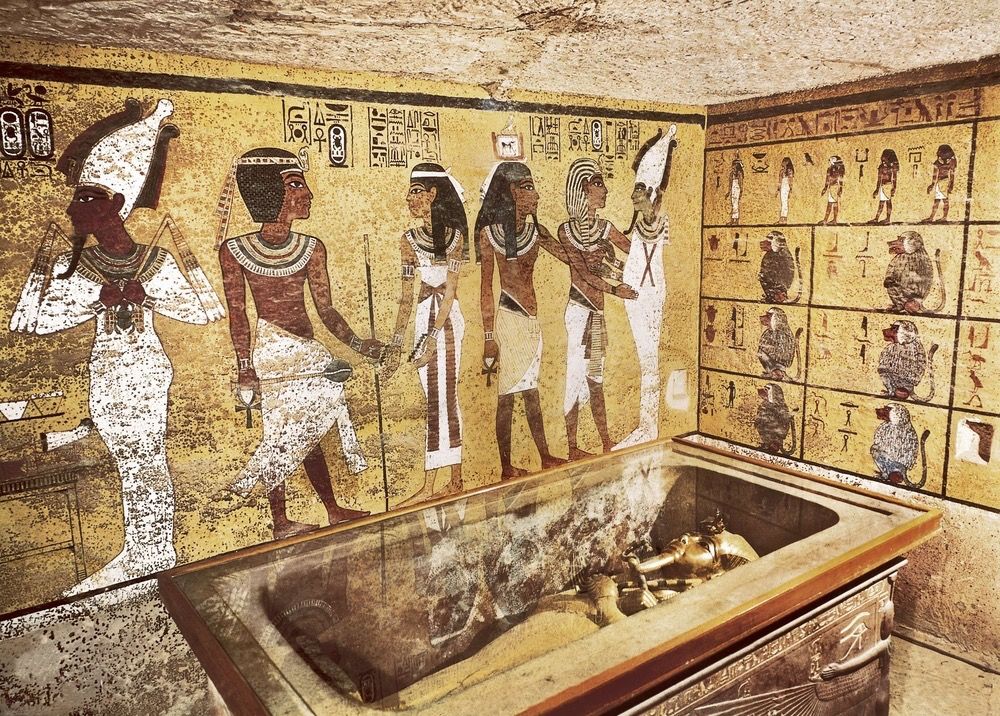

Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves, director of the Amarna Royal Tombs Project, claimed last year that the tomb of King Tutankhamun holds a hidden doorway that leads to the tomb of Queen Nefertiti, the stepmother of Tutankhamun.

Scans carried out last year by radar technologist Hirokatsu Watanabe supposedly showed evidence of two hidden chambers, along with metal and organic artifacts. The findings spurred Egypt's antiquities ministry to issue a statement saying that it was nearly certain that hidden chambers exist in Tutankhamun's tomb.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, when radar images from Watanabe's scans were released, experts voiced doubts to Live Science that the chambers existed. A new team of researchers supported by the National Geographic Society then conducted a second series of scans.

Ministry refuses to accept results

Egypt's antiquities ministry has refused to accept the new results, telling Live Science that it plans more tests to search for a tomb. "Other types of radar and remote-sensing techniques will be applied in the next stage. Once they are determined, we shall publish the updates," the ministry told Live Science in a statement.

Additionally, at a conference on Tutankhamun held this past weekend at the Grand Egyptian Museum, the researchers who conducted the radar survey were not allowed to present their research. Watanabe and Reeves, in contrast, were able to present their full papers.

Egyptologist Zahi Hawass, a former minister of antiquities for Egypt, criticized the situation at the conference, urging those in charge to accept that Tutankhamun's tomb simply does not contain a secret chamber. "If there is any masonry or partition wall, the radar signal should show an image," he said, according to National Geographic News. "We don't have this, which means there is nothing there."

Lawrence Conyers, a professor at the University of Denver who literally wrote the book on the use of ground-penetrating radar (GPR) in archaeology, said that he would like to read Goodman's scientific report. He added that he is disappointed that it is not being released.

"All I know is that I am happy I didn't fly half the way around the world to get mixed up in this mess," he said in an email.

Conyers said that if ground-penetrating radar shows no hidden chamber, then there likely isn't one. "So, I guess they are going to try other geophysical methods? I am not at all sure what those might be. They used the most obvious one, which is GPR. The others are much less definitive than GPR, so I suspect this is just blowing smoke," Conyers said in an email.

Where is Queen Nefertiti?

The whereabouts of Queen Nefertiti remain unknown. She was married to Akhenaten, a pharaoh who spurred a religious revolution. He tried to focus Egypt's polytheistic religion around the worship of the sun-disc, Aten. In doing so, he unleashed an iconoclasm that saw the names of Amun, a preeminent Egyptian god, and his consort, Mut, erased from monuments and documents throughout Egypt's empire.

Akhenaten also built an entirely new capital city at an uninhabited site, now called Amarna. Akhenaten's religious revolution ultimately died with him, and his son, Tutankhamun, disowned it a few years after his father's passing.

Many archaeologists have said that Nefertiti was buried in one of Amarna's tombs. These tombs were plundered after Akhenaten's death, the city becoming abandoned within a few decades of the pharaoh's passing.

Archaeologists have speculated that if Nefertiti's body survived the plunder, it could have been re-buried in the Valley of the Kings, and her remains could be one of a number of mummies whose identities have yet to be confirmed.

Reeves, who made the original claim about the hidden rooms, did not return requests for comment.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.