'Grizzly Adams' Conservationist Tries to Save a Last Frontier (Op-Ed)

Gordon Chaplin is a research associate at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. A former journalist who has written for the Baltimore Sun, Newsweek and The Washington Post, Chaplin now writes novels and works on the conservation of nature with the nonprofit Niparaja. Chaplin contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

The spectacular Sierra de la Giganta coast along the Sea of Cortez in southern Baja California, Mexico, is one of North America's last frontiers. It's as if the Grand Canyon had been divided at the bottom and one half moved to the sea. There are no roads, and almost no sign of humanity other than a couple of tiny fishing villages — just 100 miles (160 kilometers) or so of heart-stopping variegated cliffs, abutments, mesas, canyons and spires, revealing different hues of red, green and brown, depending on the time of day. There are very likely more big-horned sheep and mountain lions in this area than there are people.

But that could change quickly.

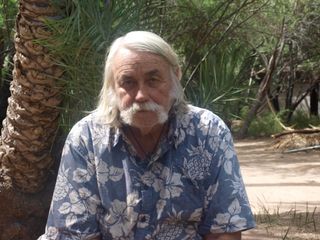

I recently sailed up this coast on a catamaran with a man who arguably knows it better than anyone alive, a 72-year-old Grizzly Adams look-alike named Tim Means. (Grizzly Adams was a famous trainer of grizzly bears and mountain man.) Means, a transplanted Arizonian who arrived in the '70s to run nature trips and never left, hopes to preserve the Sierra de la Giganta. He's been a Mexican citizen for longer than he's been an American, speaks perfect colloquial Spanish, and has raised two children there. [Nature's Arches: Photos of Stunning Sandstone in the American Southwest]

Twenty-five years ago, Means and some naturalist friends formed the conservation nonprofit Niparaja, named after the Pericu god of creation. So far, Niparaja has been instrumental in saving from developers at least two natural wonders of southern Baja: Espiritu Santo island and Balandra Bay. And they are hard at work saving the Sierra de la Giganta coast. But the developers are gaining strength as visitors from the United States and Canada flood the area in ever-increasing numbers.

In Mexico, developers usually get what they want, Means has found. In southern Baja, they've turned Los Cabos,thirty years ago just two small villages along one of the world’s most spectacular coasts into a sort of Miami Beach, with a line of high-rise hotels blocking access to the water,. Loreto, a couple hundred miles north on the Sea of Cortez, features the 6,000-unit Loreto Bay complex, billed as the largest sustainable urban development project in North America. The little farming and fishing village of Todos Santos, on the Pacific coast, 50 miles (80 kilometers) north of Cabo, has been fighting off a huge project that would double its size, take much of its water, and commandeer a beach traditionally used by the fishermen. That project, Tres Santos, has been advertised as a community for "mindful living" that focuses on the tradition of sustainability. Construction continues, in spite of vigorous local opposition, because in Mexico, from my perspective, it's who you know that counts, and the developers have powerful friends.

For the past five years, Means, backed by Niparaja, has been lobbying hard for the federal creation of a biosphere reserve in the Sierra de la Giganta, and amazingly enough, Mexico's ultraconservative pro-business and development President Enrique Peña Nieto has indicated he will issue a decree later this year to do just that. He won't be the first president to make such a promise, though. In other words, this comes under the heading of "pie in the sky." And it might give you an idea of the constraints Means faces.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the meantime, one of Niparaja's more successful approaches has been to buy up land, using funds from a wide assortment of foundations, and place conservation easements on it. They are now putting together an 80-mile-long (130 km) protected corridor along the Sierra de la Giganta coast, south of Loreto. The protections, if enacted, would make commercial development there almost impossible.

But the Sierra de la Giganta is like the Wild West: Whoever gets there first with the most money tends to win the prize. Much of the land is owned by collectives called ejidos, set up in the 1930s after the Mexican Revolution to redistribute large holdings to the peasants. However, the use of these ejidos can be controversial and heavily influenced by politics. At this moment, anti-conservation political agents have infiltrated their meetings and are doing their best to discredit Niparaja, saying the nonprofit is out to curtail ranching, fishing, development and almost any other productive activity.

Titles are vague and ambiguous, and can be disputed easily. A buyer has to be constantly vigilant; some have been known to use force to stake their claims, ripping up competitors' private property signs and posting their own, or bodily ejecting other claimants.

This has been the case with one of the few privately held lands on the coast, now claimed by an arch-enemy of Means — a man I'll refer to as Pancho Prieto. He has staked out almost 2,000 acres (8 square kilometers) of choice property with good wells, appropriating the water for his own use and forcing out many longtime residents. Prieto is extremely unpopular in his hometown on the Pacific coast of Baja because his fortune comes from shortchanging ejido members for their land and selling it at large profits to foreigners. This could be happening on his property here very soon.

But the title to his land on the Sierra de la Giganta coast is as vague as all the rest. Niparaja is hoping to acquire it, or at least to establish a conservation easement. that would prohibit subdivision and development. The fight is on.

After a two-day trip from La Paz, the capital city of Baja California, we dropped anchor off a long, red crescent beach backed by a grove of date palms that guarded a wide valley ringed by a 2,000-foot (600 m) escarpment. Means thought he had bought this 5,000-acre ranch about 20 years ago from an American; there, he had built a palapa and a strong house, and had spent good times there with his family, guests and nature tour clients.

The ranch would have made an important part of the coastal conservation corridor envisioned by Means and Niparaja, so he resigned from its board to avoid a conflict of interest and arranged to sell it the land. But the ensuing title search revealed that Means' actual property was about 10 miles (16 km) up the coast, and much smaller. He sold this to Niparaja instead and turned his attention to securing the ranch that he thought had been his all along.

He found that the ranch was actually "national land" owned by the federal government, and got an "act of possession" allowing him to use it for several years. To actually buy it, he must request an appraisal, which would be followed by an auction.

In the unlikely event that a biosphere reserve is actually created, Means could still be granted title under the biosphere regulations, but more likely, private ownership would be limited. In Mexico, a biosphere is basically a loosely regulated national park, but unlike U.S. parks, it includes support for sustainable livelihoods. Critics have called the amorphous concept "simply another line on the map." Supporters point out that, within a biosphere, it's easier to get funding for conservation projects.

Means has more pressing problems. From the deck of our catamaran, he pointed to a tiny, almost invisible structure high on the rim of the escarpment surrounding the valley. "That's where the road ends," Means said. "A developer from Constitution (the nearest large town) built that palapa so he can spy on us. He's been trying to get this place for years." A few weeks earlier, in fact, this same developer was seen on the property in the company of financiers, possibly tied to the sale of drugs, from Mexico City — "narco money," as Means put it.

The fight is indeed on, the stakes are high and I'll put my money on Means. In the past, he's outmaneuvered the best (or worst) of them. He likes to joke that his work as a repo man to put himself through college has come in very handy. I'll go so far as to propose my old friend is nothing less than the Pancho Villa of conservation in Baja Sur.

Gordon Chaplin is the author of the novel Joyride and several works of nonfiction, including "Dark Wind: A Survivor’s Tale of Love and Loss" and "Full Fathom Five: Ocean Warming and a Father’s Legacy." A former journalist for Newsweek, the Baltimore Sun, and the Washington Post, he has worked on sea conservation with the group Niparaja, and since 2003 has been a research associate at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. He lives with his wife and daughter in New York City and Hebron, New York. Gordon's latest, "Paraiso," a genre-bending novel about love, sibling relationships, and the dark side of paradise, is out this July from Skyhorse Press. He lives with his wife and daughter in New York City and Hebron, New York. Follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science .