'99 Percent Chance' 2016 Will Be Hottest Year

Global temperatures have been hovering around 1.5°C (2.7°F) above pre-industrial averages — a threshold that's being considered by international negotiators as a new goal for limiting warming.

While an exceptionally strong El Niño has provided a boost to temperatures in recent months, the primary driver has been the heat that has built up from decades of unabated greenhouse gas emissions.

Nearing 1.5°C

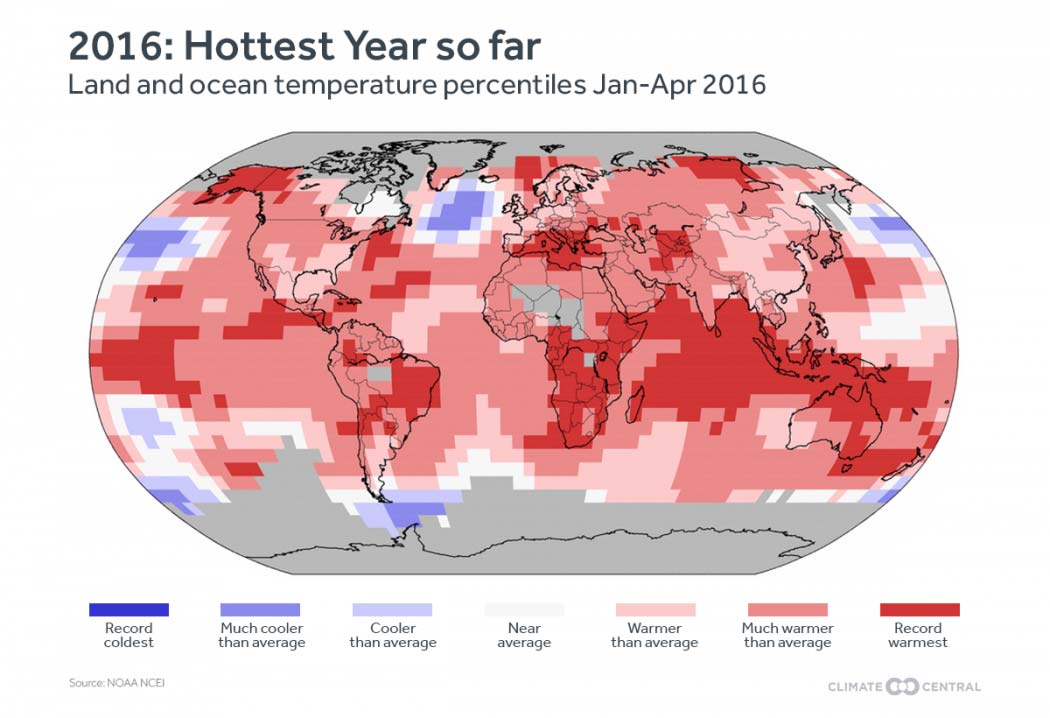

NOAA announced its temperature data for April on Wednesday, with the month measuring 1.98°F (1.1°C) above the 20th century average of 56.7°F (13.7°C). It was warmer than the previous record-hot April of 2010 by 0.5°F (0.3°C).

NASA's data showed the month was about the same amount above the average from 1951-1980. The two agencies use different baselines and process the global temperature data slightly differently, leading to potential differences in the exact temperatures anomalies for each month and year.

Both agencies' records show that global temperatures have come down slightly from the peaks they hit in February and March, which ranked as the most anomalously warm months by NASA and NOAA, respectively.

Flirting with the 1.5°C Threshold Could Baby Steps Be the Best Global Climate Strategy? See Earth's Temperature Spiral Toward 2°C

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

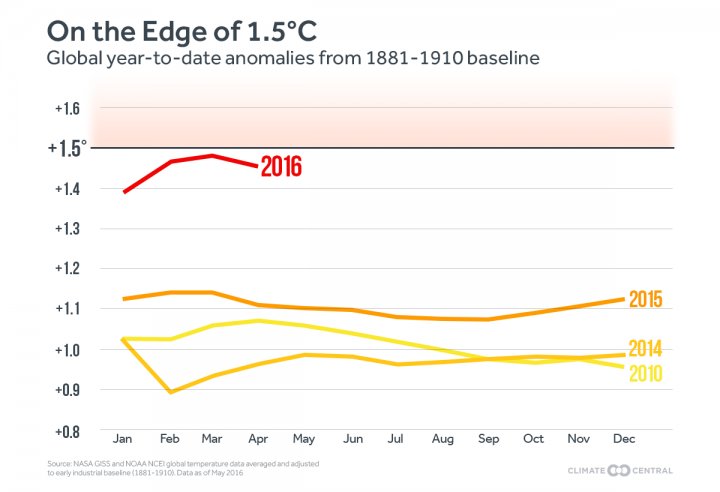

Climate Central has reanalyzed the temperature data from recent months, averaging the NASA and NOAA numbers and comparing it to the average from 1881-1910 to show how much temperatures have risen from a period closer to preindustrial times.

The analysis shows that the year-to-date temperature through April is 1.45°C above the average from that period. Governments have agreed to limit warming this century to less than 2°C from pre-industrial times and are exploring setting an even more ambitious goal of 1.5°C, which temperatures are currently close to.

"The fact that we are beginning to cross key thresholds at the monthly timescale is indeed an indication of how close we are getting to permanently exceeding those thresholds," Michael Mann, a climate scientist at Penn State, said in an email.

It will take a significant effort to further limit emissions of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases to realize those goals, experts say. Carbon dioxide levels at the Mauna Loa observatory in Hawaii are already poised to stay above 400 parts per million year-round. They have risen from a pre-industrial level of 280 ppm and from 315 ppm just since the mid-20th century.

Hottest Year?

As El Niño continues to rapidly decay, monthly temperature anomalies are slowly declining. They are still considerably higher than they were just last year, the current title-holder for the hottest year on record.

Given the head start this year has over last, there is a more than 99 percent chance that 2016 will best 2015 as the hottest year on the books, according to Gavin Schmidt, head of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, which keeps the agencies temperature data.

If 2016 does set the mark, it will be the third record-setting year in a row.

It is likely, though, that the streak would end with this year, as a La Niña event is looking increasingly likely to follow El Niño, and it tends to have a cooling effect on global temperatures.

But even La Niña years today are warmer than El Niño years of previous decades — a clear sign of how much human caused-warming has increased global temperatures. In fact, the planet hasn’t seen a record cold year since 1911.

You May Also Like: Power Plant Emissions Fall to Lowest Level in Decades Marine Parks Help Global Fish Stocks Withstand Warming Sea Level Rise Could Help Marshes Ease Flooding CO2 Nears Peak: Are We Permanently Above 400 PPM?

Originally published on Climate Central.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.