How to Start an Exercise Routine and Stick to It

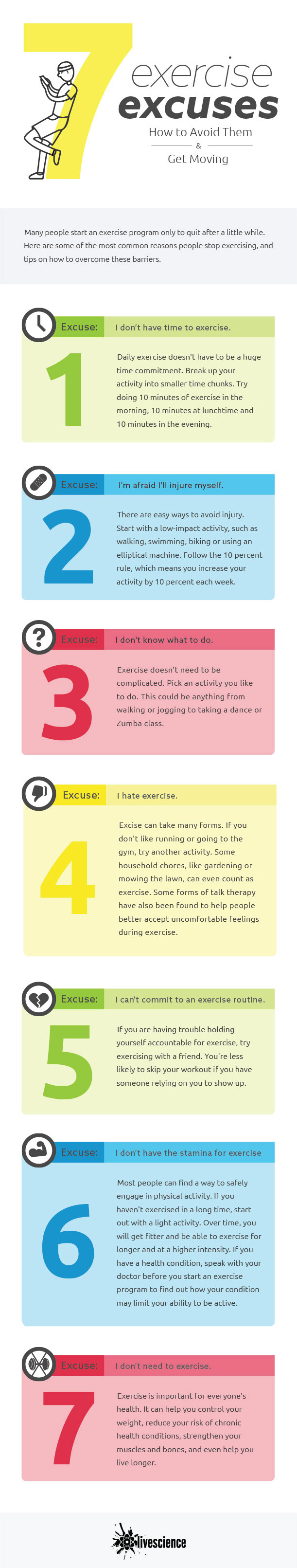

If you're like a lot of people, you made a resolution to start exercising this year, but you didn't see it through. Maybe you were too busy, afraid of hurting yourself or just hate going to the gym.

If you fall into this camp, don't give up yet. Science has found a number of ways to boost your chances of keeping up an exercise routine. To find out the best way to start exercising, Live Science consulted the latest exercise guidelines and interviewed experts in sports medicine and exercise physiology. We wanted to know how much exercise people need to do to be healthy, what exercises they should do and how they can avoid injuries when starting out.

Experts said that exercise doesn't need to be complicated or expensive; you don't have to join a gym or buy new workout clothes to become more active. And there's no single workout routine or type of exercise that's considered "the best." The most important thing is that you like the activity you choose to do. This could be anything from walking or swimming to taking a dance class.

"You should pick an exercise program that fits you," said Dr. Michael Jonesco, a sports medicine physician at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. To start exercising, you have to be willing to make a lifestyle change, he stressed. "You have to enjoy it. It has to be affordable [and] reasonable within time constraints. That's the best exercise program for anybody, because it's sustainable," Jonesco said.

Below, we'll review the basics of starting an exercise program. It's important to note that although moderate physical activity, such as brisk walking, is safe for most people, if you have a chronic health condition, or if you're worried about whether you're healthy enough for exercise, you should speak with your doctor before beginning any exercise program.

How much exercise do you need?

According to the most recent physical activity guidelines from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), adults should get 150 minutes (2.5 hours) of moderate-intensity physical activity per week. There are many ways to divide up those 150 minutes over the course of a week, but most experts recommend breaking up that time into 30 minutes of physical activity, five days per week.

But you don't necessarily have to block out a continuous half-hour to do your exercise for the day. As long as you're active for at least 10 minutes at a time, your activity will count toward your overall exercise for the day, said Dr. Edward Laskowski, co-director of Mayo Clinic Sports Medicine in Rochester, Minnesota. For example, you could walk for 10 minutes before work, another 10 minutes during your lunch hour and another 10 minutes after dinner, Laskowski said. [How Short Bursts of Activity Can Get You Fit]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It doesn't have to be one single session" of exercise, Laskowski said. "The more we do move [during the day], the better the health benefits," he said.

Indeed, a number of studies suggest that doing three separate 10-minute bouts of exercise daily is just as good as getting 30 continuous minutes of exercise. For example, a 2001 study of overweight women found that those who exercised in 10-minute bouts at a moderate intensity, three times a day, saw just as much improvement in their aerobic fitness (as measured by VO2 max, or the maximum amount of oxygen used by the body per minute) as those who exercised for 30 minutes all at once. Both groups also saw similar reductions in their weight over 12 weeks.

It's not yet clear if bouts of exercise that are even shorter than 10 minutes, but that still add up to 30 minutes a day (for example, six 5-minute workouts) can be recommended to benefit health. However, some recent studies suggest that such shorter bouts do, indeed, have health benefits. In a 2013 study of more than 6,000 U.S. adults, researchers compared people who met the physical activity guidelines (30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise daily) by exercising in bouts of 10 minutes or less to people who exercised for longer periods. They found that both groups fared similarly in terms of key markers of health, such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels and waist circumference.

If you do more vigorous activity, like running, you can spend less total time exercising each week. The HHS guidelines say that 75 minutes (1 hour and 15 minutes) of vigorous activity per week is equivalent to 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week. A recent study also found that as little as 1 minute of all-out sprinting, along with 9 minutes of light exercise, leads to similar improvements in health and fitness as a 50-minute workout at a moderate pace, when done three times a week for 12 weeks. [Just How Short Can Your Workout Be?]

The HHS exercise guidelines also recommend that people do muscle strengthening activities at least two days per week. Strength training is important for building muscle mass, which increases the number of calories the body burns overall. In addition, if you don't do strength training, the body will naturally lose muscle mass with age, and your body fat percentage will increase, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Strength training also helps to strengthen bones, which reduces the risk of osteoporosis, the Mayo Clinic says.

Strength training includes any exercises that challenge the muscles with resistance, Laskowski said. For example, push-ups (either on the floor, or the easier version, done against a wall), sit-ups, weight lifting or even intense gardening, like digging and shoveling, work to strengthen muscles, according to HHS.

How do you get started?

Although the goal is to do 30 minutes of exercise in a single day, you might need to work up to this amount if you've previously been sedentary.

A general rule is to "start out low, and progress slow," Laskowski said. This means starting with a level of activity that's fairly light, and gradually increasing the duration and intensity of your exercise.

Kelly Drew, an exercise physiologist with the American College of Sports Medicine, said she usually recommends starting with 20 minutes of exercise a day, three days a week. From there, people can increase the duration of their exercise so that they reach 30 minutes a day, three days a week. Once they can accomplish this, they can start adding more days of exercise, until they get to five days a week, Drew said.

"If people go from zero to 100, they're not going to stick with the program," Drew said. Rather, it's better to "start with small chunks [of exercise], and add it in, to where it's part of your lifestyle," she said.

How do you avoid injury?

Although it's important to pick exercise activities that you enjoy, the experts also emphasized that if you're just starting out, low-impact types of exercise are best. Good ones to try include walking, swimming, biking or using an elliptical machine.

Low-impact exercises are best for exercise beginners because they're easy on the joints and muscles, Laskowski said. By contrast, high-impact exercises, which involve lots of jumping or ballistic movements (think CrossFit or an exercise boot camp), put more stress on the muscles and joints, and can cause injuries such as strains or sprains when you're just starting out, Laskowski said.

People should also start with an honest evaluation of their current fitness level and capabilities, Drew said. For example, a person who used to do football drills in high school but hasn't done those drills in 20 years could injure himself or become sore if he tried to do those drills again right away, Drew said.

Following the "10 percent rule" also may help people avoid injuries. This means you increase your activity by 10 percent per week. For example, if you jog for 100 minutes during one week, you should aim for 110 minutes the next week, Drew said. [Aerobic Exercise: Everything You Need to Know]

As you become fitter, you should be able to do longer and more intense exercise. "The body is amazing in its ability to adapt, and the more established you become in a workout program, the more your body is going to be able to withstand the stresses that's put on it," Jonesco said.

How do you keep up a routine?

There are many barriers to exercising regularly. The biggest issue for most people is time, Drew said. "No one has time to exercise — it's about finding the time, making the time," she said.

As little as 10 minutes of exercise can be beneficial, so people can look at their schedules to see where they might fit in 10 minutes of exercise, Drew said. This can be as simple as parking a little farther from your workplace, and walking 10 minutes to and from your car, Drew said.

Setting a specific exercise goal, such as running a 5K or improving your time, can also help you stay motivated to keep up your routine, Drew said. [Need Motivation? 4 Scientific Reasons to Exercise]

It may also be a good idea to exercise with a friend, or to get a personal trainer, which holds you accountable. "You're a lot less likely to miss [a workout], because you have someone waiting for you," Drew said.

And if you think you just hate to exercise, you might benefit from a type of talk therapy that helps people accept negative feelings and uncomfortable sensations. Several recent studies suggest that this therapy, called acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), can boost people's physical activity levels and improve fitness in those who previously didn't exercise at all. [Hate Exercise? How Talk Therapy May Help]

What if you have a chronic health condition?

People with chronic health conditions should speak with their doctor before they begin an exercise program, to find out how their condition may limit their activity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. You can work with your doctor to come up with a routine that fits your abilities, the CDC says.

If you haven't previously been active, or if you have risk factors or symptoms of heart disease, you may need an exercise stress test to determine if your heart is healthy enough for physical activity, said Dr. Andrew Freeman, a cardiologist and assistant professor at National Jewish Health hospital in Denver. This is important because strenuous exercise may precipitate a heart attack in people who are out of shape and have risk factors for a heart condition, Freeman said.

An exercise stress test, which is often done on a treadmill, involves gradually increasing your exercise effort while having your heart and blood pressure monitored. The heart is monitored with electrodes on the chest, which doctors use for an electrocardiogram (ECG), and blood pressure is monitored with a blood pressure cuff on the arm.

This test can help check for coronary artery disease, a narrowing of the arteries that supply blood to the heart. The test can also identify abnormal heart rhythms during exercise, according to the National Institutes of Health.

If you've had a recent heart attack or heart surgery, a type of program known as cardiac rehabilitation can help you exercise safely, and improve outcomes. This can involve a supervised exercise program that lasts several months and gets harder as the weeks go on, Freeman said.

Another common chronic disease that may require people to take precautions while exercising is diabetes. Exercise is good for the management of diabetes, but it can cause your blood sugar to drop, Drew said. Therefore, people with diabetes should not exercise on an empty stomach, and should check their blood sugar level before and after exercise, to make sure it's not dropping too low, Drew recommended.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.