Why Is Mount Everest So Deadly?

In April, climbing season for Mount Everest opened after two years of disasters shuttered the mountain earlier than usual. In that time, there have already been four confirmed deaths. Two more climbers are missing and are unlikely to be found, experts say. One worker died while fixing a route near the summit. The other three deaths were climbers, all suspected of having altitude sickness.

In 2014, Everest expeditions almost completely halted following the deaths of 16 Nepali mountain workers in an avalanche and subsequent protests for improved work conditions. Then, in April 2015, a 7.8-magnitude earthquake and avalanche caused nearly 8,500 deaths in Nepal and resulted in 19 fatalities at Mount Everest Base Camp, leading to the cancellation of the climbing season, a choice made on the Tibet side by the Chinese government and by individual teams on the Nepal side.

So what makes Mount Everest such a dangerous place? In addition to the capriciousness of Mother Nature and the treacherous terrain on the lofty peak, the altitude can take a real toll on the human body, scientists say.

Altitude sickness on Mount Everest

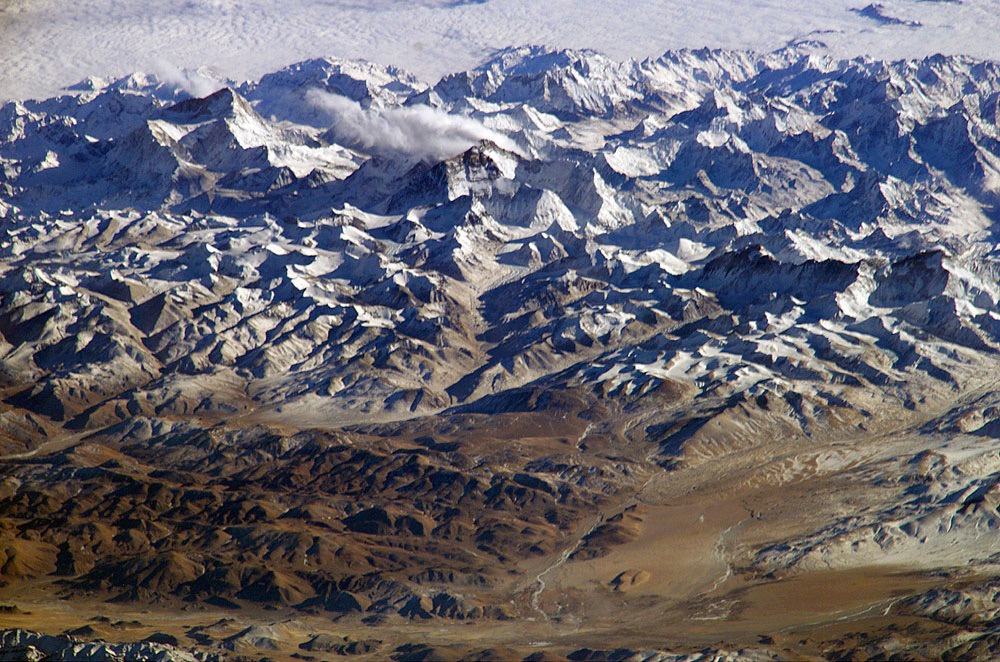

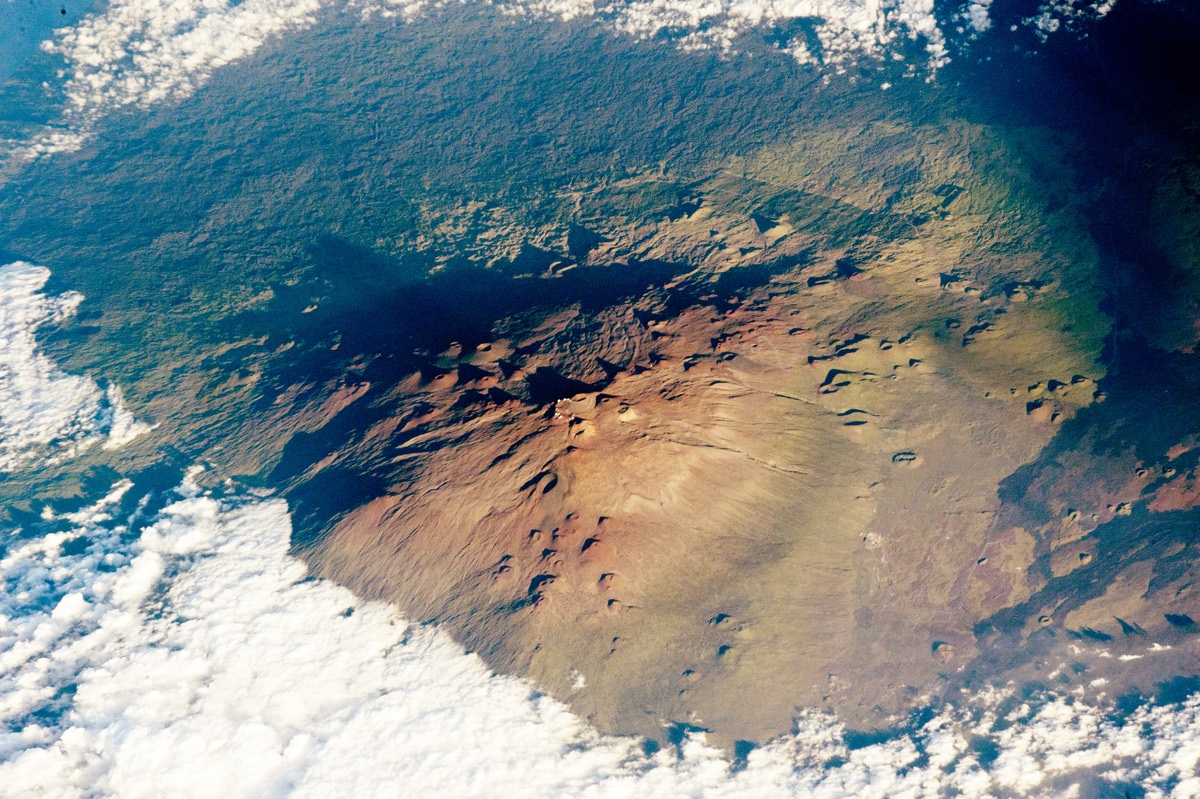

At 29,029 feet (8,848 meters), Mount Everest is the highest mountain in the world in terms of altitude. However, the tallest mountain is actually Mauna Kea in Hawaii, which measures 33,480 feet (10,205 m) from its underwater base to its peak, according to Guinness World Records. (Most of Mauna Kea is underwater.) [Photos: The World's 10 Tallest Mountains]

Altitude sickness, also called acute mountain sickness, can begin once a person reaches an altitude of about 8,000 feet (2,440 m). Symptoms include nausea, headache, dizziness and exhaustion. Many Colorado ski resorts surpass this altitude.

If climbers remain below 12,000 feet (3,600 m), they are unlikely to experience the more severe forms of altitude sickness, which may cause difficulty walking, increased breathlessness, a bubbling sound in the chest, coughed-up liquid that is pink and frothy, and confusion or loss of consciousness, according to the U.K.National Health Service (NHS).

Oxygen insufficiency is the root of altitude sickness. The barometric pressure decreases at high altitudes, which allows oxygen molecules to spread out, according to Dr. Eric Weiss, a professor of emergency medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine and founder and former director of the Stanford Wilderness Medicine Fellowship. At Everest Base Camp on the Khumbu Glacier, which lies at an altitude of 17,600 feet (5,400 m), oxygen levels are at about 50 percent of what they are at sea level. That drops to one-third at Everest's summit, which reaches about 29,000 feet (8,850 m) above sea level. [Infographic: Take a Tour Through Earth's Atmospheric Layers]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The marked reduction in barometric pressure and oxygen you get has very deleterious effects on the brain and the body," Weiss told Live Science.

If someone is experiencing mild altitude sickness, they should not go any higher for 24 to 48 hours, according to the NHS. If symptoms don't improve, or if they worsen in that time, the NHS advises descending 1,640 feet (500 m). Severe altitude sickness is a medical emergency that requires immediate descent to a low altitude and attention from a medical professional.

Altitude sickness can lead to pulmonary or cerebral edemas, which are buildups of fluid in the lungs and brain, respectively. These symptoms often occur together and are the body's attempt to get more oxygen to these vital organs in response to the decreased oxygen environment at these high elevations, said Weiss. Because blood vessels and capillaries are porous, this increased flow can cause leakage and fluid retention. Fluid buildup in the brain may result in loss of coordination and problems with thought processing, said Weiss. It can lead to coma and death. Weiss said that fluid buildup in the lungs can make it hard for someone to breathe and physically exert themselves. It can eventually cause death through a process similar to drowning.

Researchers reporting in 2008 in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) looked at deaths on Everest from 1921 to 2006 and found that "profound fatigue and late times in reaching the summit are early features associated with subsequent death," they wrote in the BMJ.

Weiss has a similar view on the safest way to climb Everest: "When people climb Everest […], the mantra is that you have to get up to the summit by a certain time so that you can get down while you still have oxygen left and while you still have daylight," he said. Too often, people refuse to turn around when they should because they can see the summit and think it's close enough to justify continuing, he added.

Why Sherpas survive

Overall, the BMJ study found that the total mortality rate for Everest mountaineers was 1.3 percent. The mortality rate for climbers is 1.6 percent, compared with 1.1 percent for Sherpas. The most common cause of death for climbers was falls, whereas the most common cause of death for Sherpas was "objective hazards," which included avalanches, falling ice, crevasses and falling rock, and were likely related to the extended time they had to spend in more treacherous areas of the mountain as part of their employment. The researchers noted that neurological dysfunction, which could be related to altitude sickness, also could have contributed to fatal falls.

There are no distinct reasons why altitude affects one person more than another. The National Institutes of Health notes that speed of ascent and physical exertion often play roles in whether someone develops altitude sickness. Acclimatization is often touted as a vital step in attempting Everest with reduced risk.

Living at high elevations, such as the elevations at which Sherpas grow up, may give certain people an advantage in climbing Everest, according to a study detailed in 2015 in the journal F1000Research. That study, which involved Sherpas and lowlanders at various elevations, including Base Camp, suggested that Sherpas may be protected from altitude sickness due to various physiological processes, including mitochondrial function and microcirculation. The mitochondria, often called the powerhouses of the cells, take in oxygen and convert it to fuel. It's possible that Sherpas' mitochondria process oxygen more efficiently, making them better suited to high-altitude environments that other people. Microcirculation is the movement of blood to the smallest blood vessels, which also includes the delivery of oxygen to bodily tissues. Research has shown that Sherpas maintain better microcirculatory blood flow in low-oxygen environments than people who are from low elevations.

The BMJ researchers noted that Sherpas may be less likely to die at the highest elevations because they spend more time up there preparing routes, further increasing the time they have to acclimate. The competitive process involved in becoming a mountain worker likely also means that only the people best suited for the job are working on Everest, the researchers added.

Tips for surviving altitude sickness

Bringing someone to a lower elevation is the best way to treat altitude sickness, but doing so can be very challenging. "Prevention is paramount, because once those changes occur at those kinds of extreme altitudes, it is very hard to assist someone to a lower altitude," Weiss said. Climbing downhill is more challenging than trekking uphill because it often requires increased coordination and technical skills, he said. Other factors — such as exhaustion, dehydration and a low supply of supplemental oxygen —can add to the difficulty. People experiencing altitude sickness also may be struggling to walk or may be unconscious, Weiss said.

There is medication that may help to prevent, and partially treat, the buildup of fluid in the brain, but it is not effective in treating the buildup of fluid in the lungs, Weiss said. Supplemental oxygen can help, but it isn't always available.

In Nepal in 1989, Weiss and his colleague Dr. Ken Zafren, also of Stanford, were the first people to field-test another potential treatment for severe altitude sickness, called the Gamow bag. The inflatable bag, which looks a little like a closed sleeping bag, can essentially create a lower-atmosphere environment for the person inside. A foot pump is used to inflate the bag, creating higher pressure inside than outside. The extent of descent this bag can simulate depends on where it's being used. At the top of Everest, it could simulate a descent of about 9,195 feet (2,800 m), according to a manual provided by the American Mountain Guides Association. Weiss said the bag is helpful but is not practical to use at Everest's summit because it weighs nearly 13 lbs. (6 kilograms) and requires a lot of physical exertion in order to inflate it and keep it inflated at extreme altitudes. A Gamow bag is almost always available at Base Camp, but the sick person must be brought to it, Weiss said.

So far this year, approximately 400 climbers have made it to the top of Mount Everest. According to National Geographic, they include Melissa Arnot, who summited for her sixth time and is the first American woman to do so without supplemental oxygen; Staff Sgt. Charlie Linville, the first combat-wounded amputee to reach the summit; and Lakhpa Sherpa, a Nepalese woman who summited for the seventh time, breaking her own record as the most accomplished female Everest climber.

Editor's Note: This article was updated to correct the description of cerebral edema.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.