10 Ways the Beach Can Kill You

Dangers in Paradise

The beach may conjure up gorgeous images of crashing waves, tan lines and afternoon siestas. But this primo vacation hotspot isn't only about fun and serenity — it's also filled with dangers that, if you're unaware of them, can wreak havoc … or at least cause bad sunburns. Live Science assesses these hazards, from deadly riptides and destructive tsunamis to venomous jellies and harmful algae blooms.

Heatstroke

Usually, the body cools itself off by sweating. But if the body's temperature control system is overloaded, beachgoers can get heatstroke, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports.

During heatstroke, the body's temperature rises quickly — up to 106 degrees Fahrenheit (about 59 Celsius) or higher within 10 to 15 minutes. This can damage the brain and other vital organs, according to the CDC.

Heatstroke often happens when humidity is high (sweat doesn't evaporate as rapidly in muggy weather, making it harder to cool off), the CDC said. Other risk factors include old age (65 years or older), youth (children ages 4 or younger), obesity, fever, dehydration, heart disease, sunburn and alcohol use, the CDC said.

Symptoms include high body temperature; red, hot and dry skin (that is, no sweating); rapid pulse; throbbing headache; dizziness; nausea; confusion; and unconsciousness, the CDC said. To help, get the person to a shady area, cool him or her down with cool water, and call emergency services, the CDC said.

Tsunamis

Beaches are prime real estate for tsunamis, so it's good to be aware of an escape route in case you're sunning on the sand when disaster hits. In fact, if you hear a tsunami warning, get out of the water, stay away from beaches and evacuate to higher ground, according to the National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program, a U.S. government program.

Tsunamis are a series of waves that are formed by sudden displacements in the seafloor, landslides, volcanic activity or earthquakes, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The name itself is pretty literal. In Japanese, "tsu" translates to "harbor" and "nami" means "wave," NOAA said.

Since 1850, tsunamis have killed more than 420,000 people. The Sumatra tsunami was one of the deadliest in recent years, killing about 230,000 people on Dec. 26, 2004, NOAA reported.

Many coastal areas now have tsunami-warning systems that monitor for earthquake activity and the passage of tsunami waves — but these instruments still can't give exact predictions of the timing and size of tsunamis, NOAA said.

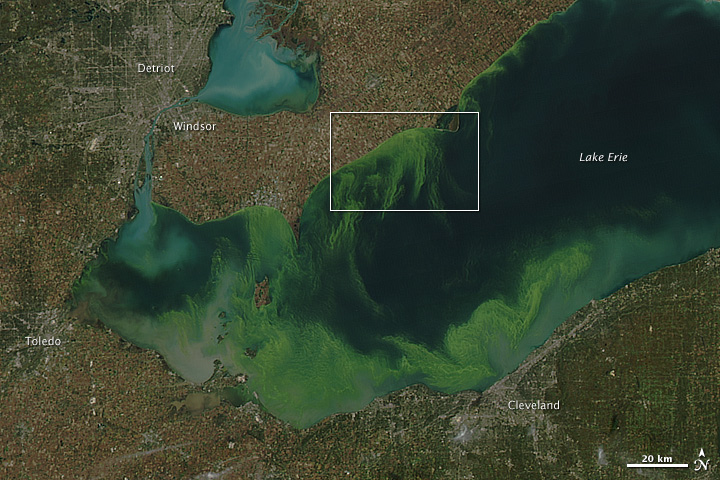

Algal blooms

Who knew something so small could be so dangerous: Harmful algal blooms, also known as red tides, happen when a colony of algae grows out of control, according to NOAA. These blooms can release toxins that harm people, fish, shellfish, other marine animals and birds, NOAA said.

One of the most famous algal blooms happens almost every summer along Florida's Gulf Coast, and it usually ends up killing fish and making shellfish unsafe to eat, NOAA said. Even nontoxic algal blooms can have disastrous effects on the ecosystem. For instance, when masses of algae die and decompose, they can deplete oxygen from the water, leaving marine creatures breathless, NOAA said.

People shouldn't eat shellfish from areas affected by toxic algal blooms. In 1990, six fishermen almost died after eating steamed mussels that they had collected from an area near Cape Cod, Massachusetts, according to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

The water may not be as tempting for swimmers, but there aren't always real health concerns linked to taking a dip in waters affected by these blooms. "Although some people can experience skin irritation and burning eyes, swimming during a red tide is safe for most people," NOAA reported. "However, never swim among dead fish, because they can be associated with harmful bacteria."

NOAA added that "If you experience adverse symptoms, get out of the water and thoroughly wash off with fresh water.”

Shark attacks

Shark attacks get a lot of attention, but they're relatively rare. For instance, 2015 had a record number of 98 unprovoked shark attacks, resulting in six deaths, the International Shark Attack File reported.

Shark biologist George Burgess, curator of the world shark-attack data at the Florida Museum of Natural History, gave Live Science some tips to prevent these rare, but terrifying, attacks:

- The most important tip is to use your common sense, Burgess said. Avoid swimming near fish. "Where there are fish, there are predators," he told Live Science. Stay away from fishing boats and areas with diving seabirds; both indicate fish are in the water.

- Avoid deep channels, troughs between sandbars and underwater drop-offs. Fish also congregate in these areas, attracting sharks.

- Stay out of murky water that makes it hard for you to see sharks, and for sharks to see that you're a human, not a fish or a seal.

- Don't swim alone. Sharks are less likely to go after groups of swimmers or divers.

- Don't swim at dawn or dusk, when sharks are more likely to be actively feeding close to shore. "A nighttime swim may be very romantic, but it's certainly not the smartest thing to do," Burgess said.

- Avoid wearing shiny jewelry or watches in the water. They gleam like fish scales.

Rip currents

Toothy sharks devouring beachgoers may get the most splash in headlines, but a more likely killer may be lurking at your favorite beach spot. Much like the name implies, rip currents are fast-moving currents of water that can pull even the strongest swimmers away from shore, according to Texas A&M University.

These tides are dangerous, killing at least 100 people a year at surf beaches within the United States, the U.S. Lifesaving Association (USLA) reported.

Rip currents, also called riptides, can happen at both the seaside and large lakes, and frequently form at low areas or breaks in sandbars or structures such as piers, according to Texas A&M. People can spot them by looking for a break in the pattern of an incoming waves, a channel with churning, choppy water, a place with noticeably different water color, or a line or foam, seaweed or debris moving seaward, the university said.

If caught in a rip current, don't fight it directly. Instead, swim in a direction that follows the shoreline, and swim back to shore once you're out of the current, Texas A&M said. If that doesn't work, float or tread water until the current stops, or call for help, the university said.

Jellyfish

Jellyfish may look squishy and pretty, but some are deadly and others can leave a stinging sore on swimmers.

Of the estimated 2,000 species of jellyfish, about 70 can cause serious harm, or even death, NOAA reports. So exercise proper jellyfish safety when chilling at the beach this summer: Look for jellyfish warning signs or announcements, and don't touch jellies that wash up on the shore, as their wet tentacles can still sting.

What's more, it's a myth that urinating on a jellyfish sting will reduce the pain, Live Science reported. Instead, find a lifeguard, who can give first aid for stings, and see a doctor if you have an allergic reaction, NOAA said.

If you're on your own, get the wound out of the water, and remove the tentacles with something other than your bare hand, Jennifer Ping, an emergency medicine physician at Straub Clinic and Hospital in Honolulu, told Live Science. Then, splash vinegar or another acidic solution on the wound, she said.

Sunburns

Slather up with sunscreen and take cover under shade to protect your skin from painful sunburns while at the beach, the CDC says.

It takes as little as 15 minutes for the sun's ultraviolet (UV) rays to damage your skin, the CDC reported. These sunburns can increase the risk of skin cancer, which 1 in 5 Americans will develop, Live Science reported.

At the expense of getting a ticket from the fashion police while relaxing on the balmy beach, to keep your skin sunburn-free, try wearing long-sleeve shirts, long skirts or pants. But make sure your clothing is dry, as wet clothes offer less UV protection than dry ones, the CDC said. If you only have a swimsuit, just remember to apply sunscreen amply and often.

Gross water

The beach can be a pristine place, so long as it's not contaminated. Avoid these bad beach days (or simply, unsafe beaches) by checking for beach closures or advisories, NOAA said.

Advisories are usually posted because of water that's contaminated, from such sources as untreated sewage from boats, pets, failing septic systems, fertilizers and hazardous spills, NOAA said.

In addition, bacteria such as E. coli and harmful chemicals in the water can cause gastrointestinal illness, NOAA reported.

Beach trash

Keep your distance from rusty metal, broken glass and other debris that is left on the beach or that washes ashore. These may even include derelict fishing gear and broken boats, NOAA reported.

"Often this debris, or litter, ends up on our beaches, damaging habitats, harming wildlife and making it unsafe for beachgoers to walk along the shoreline and swim in the water," NOAA said in a statement.

Beachgoers can help clean up by getting involved with NOAA's Marine Debris Program or the nonprofit program, Ocean Conservancy.

Collapsing Sand Holes

Beachgoers, especially kids, often enjoy digging deep into the sand. But these holes can collapse and bury people within them, physicians report.

A 2007 report, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, documented 52 fatal and nonfatal cases of these sandy collapses over a 10-year period. The victims ranged in age from 3 to 21, and 45 (87 percent) of them were male, the report found.

Most cases happened near the shoreline, with holes both small and big, ranging from 2 feet to 15 feet (0.6 to 4.6 meters) in diameter, and 2 feet to 12 feet (0.6 to 3.7 m) deep.

"Typically, victims became completely submerged in the sand when the walls of the hole unexpectedly collapsed, leaving virtually no evidence of the hole or the location of the victim," the researchers said.

These collapses are often triggered by digging, tunneling, jumping or even falling, and led to the deaths of 31 people. The other 21 people survived because of swift rescue and medical care, the report said.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.