Abri Faravel: Photos of Prehistoric Rock Paintings

Abri Faravel

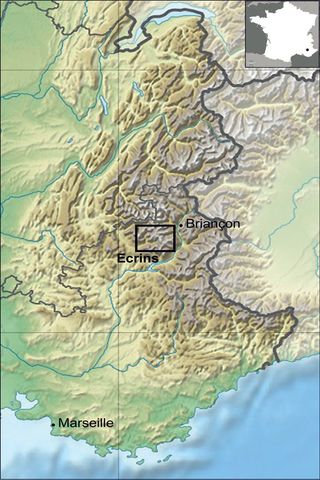

The highest known rock art is on a plateau in the French Southern Alps, located in the box on this map. Abri Faravel is a small rock shelter with several red rock paintings inside, including a series of parallel lines and what appears to be two deer or other animals facing each other. The site is at nearly 7,000 feet (2,133 meters) above sea level. [Read the full story on Abri Faravel]

Prehistoric Art

The rock paintings at Abri Faravel, shown on the left in normal light and on the right with digital enhancement. The paintings are simple and depict a series of parallel lines along with two animal figures. [Read the full story on Abri Faravel]

The Faravel plateau

The Faravel plateau, viewed from the north, with an arrow showing the location of Abri Faravel. The rock shelter shows archaeological evidence of use starting in the middle Stone Age (between about 10,000 and 5,000 B.C.) extending all the way into the Middle Ages. [Read the full story on Abri Faravel]

Above Treeline

A view of the Faravel plateau and Abri Faravel from the southeast, with an arrow pinpointing the rock shelter. The shelter isn't the only sign of human habitation on the plateau. Archaeologists have also found flint tools, pottery shards and even Medieval metalwork. Stone buildings were erected in the Bronze Age, perhaps for use as animal pens or by cheese-makers. [Read the full story on Abri Faravel]

Rock Shelter Collage

This collage shows views from in and around the Abri Faravel rock shelter. Though the overhang is now above treeline, it likely would have been at the edge of a forest during the Stone Age, making it a good spot for hunters to watch for game. The rock paintings are visible in middle-right photograph, which shows the view from inside the shelter. [Read the full story on Abri Faravel]

Enhanced Rock Art

A view of the rock paintings from the interior of the Abri Faravel rock shelter. The colors have been enhanced for contrast. These paintings were first discovered in 2010 and are the highest-elevation rock art ever known. [Read the full story on Abri Faravel]

Scanning the Rock

Researchers had to use car batteries to power their lights in order to capture 3D digital images of the rock shelter and the paintings. They published their results in the journal Internet Archaeology on May 25, 2016, including a 3D digital model that users can navigate through to understand the landscape. [Read the full story on Abri Faravel]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Laser scan at Abri Faravel

Researchers conduct a laser scan near the Abri Faravel rock shelter to capture the area's topography. In the Neolithic (5500 B.C. to 2800 B.C.), people farmed the valleys below the plateau and apparently used the higher elevations as hunting grounds, based on finds like arrowheads and a stone ax. [Read the full story on Abri Faravel]

High-Altitude Archeaology

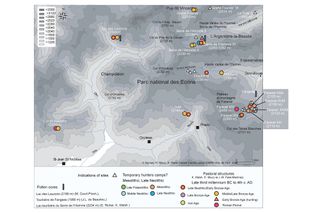

This map shows the distribution of high-altitude archaeological sites near Faravel (which can be seen in the center-right of the map). Researchers study these sites to understand how prehistoric peoples used these relatively unwelcoming environments. [Read the full story on Abri Faravel]

Mesolithic Treeline

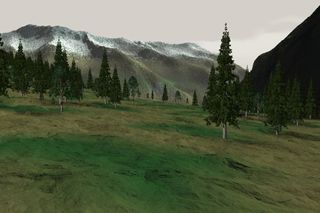

A virtual reconstruction of the treeline in the Mesolithic, which would have been slightly higher than the Abri Faravel rock shelter. Mesolithic hunters might have used the shelter as a place to wait for game coming out of the forests and headed toward nearby streams. [Read the full story on Abri Faravel]

Stone Axe

A Neolithic (5500 B.C. to 2800 B.C.) stone axe found not far from Abri Faravel. Finds like this suggest that people hunted for game in the mountains even as they farmed the valleys below. [Read the full story on Abri Faravel]

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular