In Photos: Tracking the Devastating Impact of the Black Death

Black Death

The 14th-century plague known as the Black Death is thought to have killed up to 60 percent of the population in parts of Europe.

The Black Death was seen by many who lived through it as a punishment from God on sinful peoples, and it had a solemn effect on European art and culture. This image, from a Flemish illustrated manuscript of 1349, shows plague victims being buried in the city of Tournai, now in Belgium.

New archaeological research has mapped the devastating impact of the Black Death in parts of England. [Read full story about the Black Death's impact]

Digging for clues

Until recently there was little archaeological evidence of the 14th century plague. But now, the results of a decade-long study, aided by a volunteer army of around 10,000 amateur archaeologists, have revealed the drastic impact of the Black Death on part of rural medieval England.

The volunteers included local families, students, landowners, and members of community groups, and they dug more than 2,000 test pits in 55 villages in eastern England to assess the impact of the Black Death. In this image, two volunteers excavate a test pit in the garden of their home, in the village of Ashwell, in the county of Hertfordshire.

Pottery and population

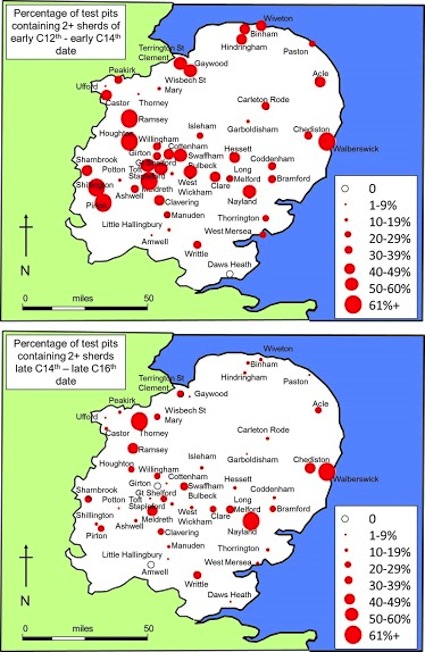

The study was directed by Carenza Lewis, an archaeologist at the University of Lincoln in the United Kingdom. She compared data about the numbers of pottery pieces dating from before the Black Death to the numbers found after the Black Death, and revealed the long term changes in population wrought by the plague.

The results showed that the surveyed villages suffered an average long-term population drop of 45 percent during the Black Death and in the years that followed.

Before and after

The study has shown for the first time how different villages were affected by the Black Death. This map shows the relative abundance of pottery finds in the 55 surveyed villages that date from in the 200 years before the Black Death (top) and in the 200 years afterwards (below).

Some villages in the surveyed area showed long-term increases in population, possibly because they were commercial communities that relied on the trade in cloth, rather than agricultural communities that needed a lot of labor to keep going, Lewis said. [Read full story about the Black Death's impact]

Helping out

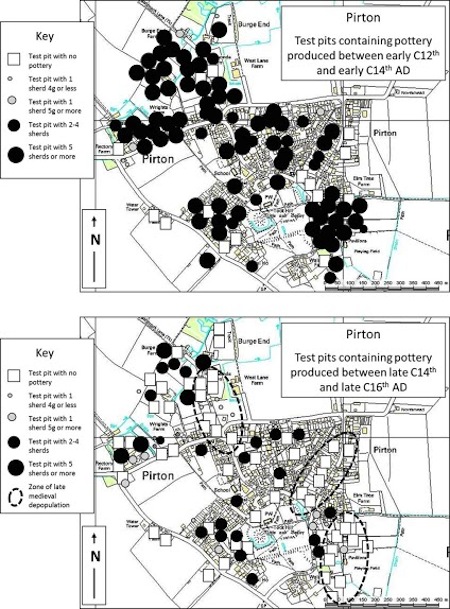

One of the worst hit villages was Pirton, in Hertfordshire, which suffered a 76 percent drop in long-term population, according to the study. This image shows volunteers digging a test pit in the garden of their home in Pirton, where 155 test pits were dug — the largest number of any of the villages in the survey.

Retired archaeologist Gil Burleigh, who organised the digs in Pirton, said the project had become a point of pride for the modern village community. "It became very big indeed. I got the local history society involved, and various residents and landowners, and it really took off," he said.

Population drop

Data from the Pirton test pits reveal how different parts of the village were affected by the Black Death. The top frame of this map of the village shows the relative numbers of pottery pieces found in the test pits that were dated to the 200 years before the Black Death. The bottom image shows the relative numbers of found pottery pieces that were dated to the 200 years after the Black Death. [Read full story about the Black Death's impact]

Key pieces

This image shows a medieval pottery sherd dated from before the Black Death.

"The pottery looks very unremarkable, the sort of bits that you wouldn’t notice if you’re just gardening," Lewis said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Community project

The community digs merged local passions for the past and modern community spirit in the surveyed villages. Andora Carver, who organised dozens of test pits in the Suffolk village of Nayland, said it took about two or three days for a team to dig, sieve and fill-in on of the pits.

Nayland was one of a few villages in Suffolk that showed an increase in population after the Black Death, possibly because it had a thriving market at that time, she said. This image shows a test-pit team at a home in the Suffolk village of Clare. [Read full story about the Black Death's impact]

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.