Best Protected Great Barrier Reef Corals Are Now Dead

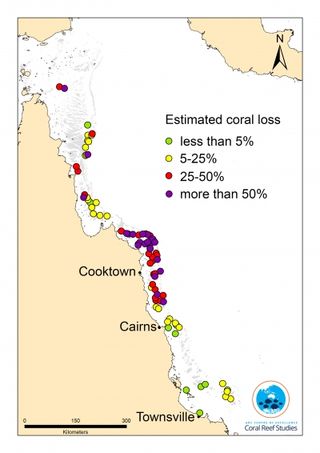

The sweeping reefs growing off 200 steamy miles of remote Australian coastline — from Cairns to Cape Melville, home to sugar farms and dive resorts — contained some of the least damaged corals growing in one of the world's best marine parks. Until now.

In stunning new findings that have laid bare the limitations of marine parks as defenses against rapid environmental change, more than half of the corals surveyed in large chunks of this pristine stretch of the Great Barrier Reef are expected to soon be dead.

"Reefs that are in better shape should fare better under climate change," said John Pandolfi, a University of Queensland professor who contributed to high-profile coral surveys, the results of which were released this week. "But, in this case, we found huge instances of coral mortality."

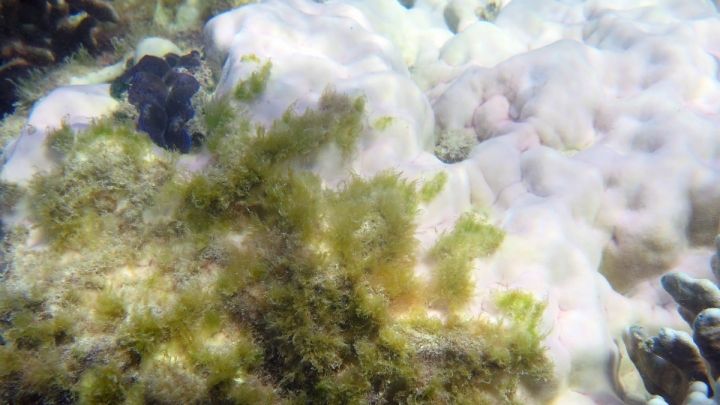

The coral deaths followed intense coral bleaching, which was caused by global warming and influenced by the whims of the weather. Hot waters have caused corals worldwide to spit out the algae that provided their color and food. Those that can't cool down and find new algae quickly enough die.

Climate Change is 'Devastating' The Great Barrier Reef Bleaching Has Hit 93 Percent of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Parks Help Global Fish Stocks Withstand Warming

The colorless coral corpses of north Queensland will soon be blanketed with mats of algae, and the hard skeletons will begin to crumble. It may take decades for the submerged wonders of what had recently been unspoiled reefs to resprout and recover from the wipeout, if they ever do.

Temperatures continue to rise worldwide. The amount of heat-trapping pollution released every year from fuel burning and deforestation has plateaued in recent years, while the amount of pollution in the atmosphere continues to pile up. Bleaching is caused primarily by warm waters, and the current worldwide bleaching is the third and worst on record, all since the late 1990s.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Things aren't going to be as good as they are now — we can look forward to some very difficult times," Pandolfi said. "The reef is going to continue to degrade."

Overall, 35 percent of the corals surveyed in the central and northern sections of the Great Barrier Reef were reported this week to be dead or dying. Scientists photographed and dove into 84 reefs and used six categories to score the condition of 200,000 corals. Dead corals could often be spotted by the algae that quickly grew over them.

The news from coral surveys south of the popular tourist city of Cairns was bleak, with about 5 percent of corals found dead or dying. But that was some 10 times better than the doom that befell reefs further north.

Corals south of Cairns appear to have been saved by the happenstance trajectory of a February cyclone, which washed them with cooler waters and churned up the sea. That protected them from the high temperatures and searing exposure to UV rays that killed so many of their cousins further north.

"We dodged a bullet in the central portion of the reef this time, but no guarantees that will occur again," Pandolfi said. "Nature is an incredibly complex place, and it's very difficult to predict how future bleaching might play out."

The discovery of the collapse of sweeping sections of corals was viewed by scientists with so much urgency that they were not put through peer review before highlights were released to the media on Monday. James Cook University, which led the surveys, declined to provide detailed information about the sampling methods or analysis, making it difficult for journalists or other scientists to evaluate or interpret the findings.

"The research is publicly funded," James Cook professor Terry Hughes said. "I released our mortality results because, as a scientist, I'm ethically obliged to inform people on an issue of national and international importance."

Hughes said details about the methodology would eventually be published. "Given the intensity of the research, there'll be many publications arising."

David Kline, a Scripps ecologist who wasn't involved with the coral surveys, said that he had "complete confidence" in the findings. "Survey methods are pretty standardized," he said. "They haven't changed much in the last 30 or 40 years."

Emotions had been running high even before Monday's news release over the future of one of the world's great natural wonders amid a two-year period of rapid global warming. Climate change made it 175 times more likely that Coral Sea temperatures would reach the high levels in March that triggered extensive bleaching, according to the results of a recent scientific analysis.

Climate research and Great Barrier Reef management are both hot political issues in Australia, where a federal election will be held next month.

The Australian government has been criticized for failing to protect the reef from agricultural pollution and other threats, including coal mining. Following a request from Australia, the United Nations recently removed information about threats to the Great Barrier Reef from a report dealing with climate change and world heritage.

The north Queensland coral wipeout occurred around the same time that global temperature rise was reaching the halfway point toward the 3.6°F of warming that a new United Nations treaty aims to prevent. Countries haven't yet committed under the Paris Agreement to take the steps needed to prevent that level of warming. Years of further negotiations are planned.

The extent of the coral wipeout was particularly remarkable because it occurred inside one of the world's best protected natural areas. Fishing restrictions and other rules are in place to protect reefs that serve as nurseries for large fisheries and as drawing cards for a tourism-heavy economy.

"The coral animal is the keystone species on a coral reef — like the trees in a forest," Kline said. "When the corals die you lose the three-dimensional structure that's really important. A lot of these fish, their larval stages depend on hiding in among the corals to hide from predators."

Kline said the Great Barrier Reef is inside what's considered to be "one of the best managed and most successful" marine parks in the world.

Large marine parks have been created around the world in rapid succession during the last decade, quadrupling the amount of protected ocean to nearly 4 percent. The U.N. aims to see 10 percent protected by 2020.

"In other parts of the world, we've had mortality events this severe," Kline said. "But everyone thought with the Great Barrier Reef marine protected area that, hopefully, we wouldn't see mortality events as high."

Kline said that means the future of coral reef environments will depend on local strategies for protecting them — in addition to a global curbing of greenhouse gas pollution. Such strategies may include farming and transplanting corals and creating artificial reefs from concrete and other material.

"Clearly, marine reserves on their own aren't enough," Kline said.

You May Also Like: The Temperature Spiral Has an Update. It's Not Pretty. America's Sickest Wetlands Are in the West, EPA Finds Global Warming Threatens the World's Special Places

Originally published on Climate Central.