19th-Century White House Garden Aligns with Solstice Sun

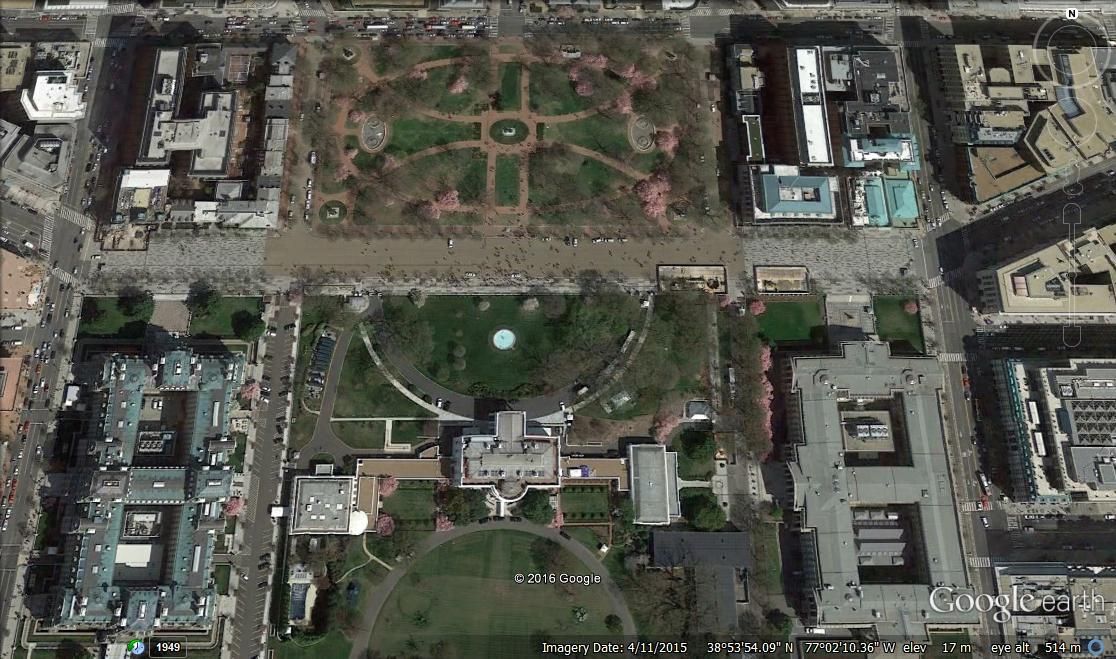

A 19th-century garden just north of the White House on Pennsylvania Avenue, in Washington, D.C., was designed so that its statues align with the rising and setting sun on the summer and winter solstices, a physics professor has found.

Using satellite imagery and astronomical software, Amelia Sparavigna, of Politecnico di Torino in Italy, discovered the phenomenon. The solstice sun aligns with the center of the garden, which contains a statue of President Andrew Jackson, and the endings of four walkways that now contain four statues of generals from the American Revolutionary War, the physicist found.

Sparavigna said she is not sure why Andrew Jackson Downing —who designed the garden and its walkways in 1851 — would have created such solstice alignments in his layout. The statue of Andrew Jackson was erected in 1853 while the statues of the four other generals were erected at the end of the walkways between 1890 and 1910. [In Photos: Peru Pyramid Shows Solstice Alignment]

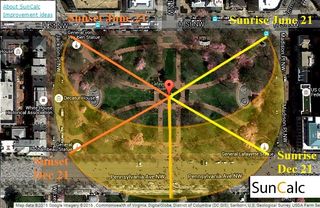

The sun's path at Lafayette Square

To see the summer solstice alignment, Sparavigna found, you'd need to stand next to the statue of Jackson, who is shown leading American forces during the Battle of New Orleans, which was fought against the British during the War of 1812.

From that spot, during the summer solstice, the longest day of the year, the sun will rise at the northeast end of the walkway, where a statue of General Thaddeus Kosciuszko is located. Kosciuszko was a general from Poland who helped win the Battle of Saratoga in 1777; that conflict stopped a British invasion of the United States from Canada.

Also, if you stay in that spot, the sun will set over the northwest end of the walkway, where a statue of General von Steuben stands. Von Steuben was a Prussian whom George Washington appointed inspector general of the Continental Army.

In the same study, detailed in the journal Philica, Sparavigna outlined a discovery about the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year. On this day, from the perspective of the Jackson statue, the sun will rise at the southeast end of the walkway where a statue of Marquis de Lafayette is located. Lafayette played an important role in several Revolutionary War battles.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Later on, the winter solstice sun will set on the southwest end of the walkway where a statue of General Rochambeau is located. Rochambeau was a French military commander who led French troops on a series of military campaigns that culminated in the British surrender at Yorktown in 1781, an event that forced the British to recognize the independence of the United States.

Why solstice alignments?

It's still unclear why Downing aligned the end of the walkways of Lafayette Square to the solstice sun, Sparavigna said. "No references to a specific planning of alignments along the solar azimuths (the angle of the sun) for the Lafayette Square are available," Sparavigna wrote in the journal article.

Sparavigna noted that aligning features to the solstice sun can be done to make planning a garden or monument easier. "Architects have six main directions: Two are joining cardinal points (north-south, east-west), and four are those given by sunrise and sunset on summer and winter solstices," she wrote in a different paper, published in 2015 in Philica.

This isn't the first garden designed with the sun in mind, and Sparavigna notes there are parallels between the design of Downing's square and gardens created in South Asia by the Mughal Empire, which flourished between 1526 and 1857. Several Mughal gardens had alignments to the solstice sun, including those at the Taj Mahal.

Like the gardens constructed by the Mughal Empire the design of Lafayette Square has "a rectangular layout, with the axis coincident to the cardinal direction north-south," Sparavigna wrote in the new paper. "Moreover, they have the solar alignments."

Historical records show that Downing never traveled to South Asia, although he did travel to Europe shortly before he started designing Lafayette Square.

Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.