'Grunt: The Curious Science of Humans at War': A Q&A with Mary Roach

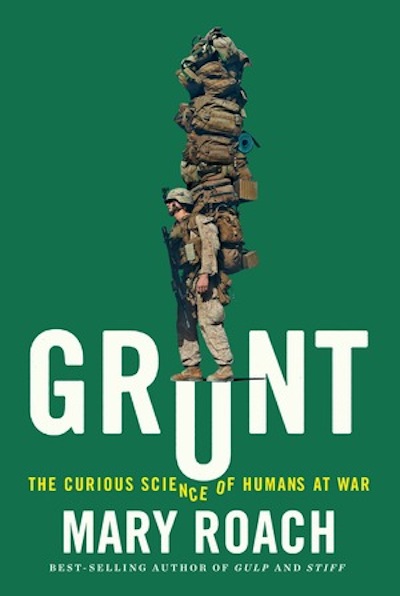

Is it possible to develop bombproof underwear? And why is it so difficult to perform a whole-body transplant? These are just some of the fascinating questions tackled by science writer Mary Roach in her new book, "Grunt: The Curious Science of Humans at War."

The book, published by W. W. Norton & Co. and scheduled for release tomorrow (June 7), dives into the science of the military — a world that encompasses research on everything from heatstroke to the medical benefits of maggots (yes, maggots). In her characteristic up-for-anything approach, Roach takes readers into the labs of the unsung heroes who are working to keep U.S. soldiers alive and safe while they're deployed. [Flying Saucers to Mind Control: 7 Declassified Military & CIA Secrets]

Roach caught up with Live Science recently to talk about her new book, why she decided to delve into military science and the weirdest chapter of World War II history that she stumbled on. (This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.)

Live Science: What got you interested in looking at the science or warfare?

Mary Roach: I was reporting a story in India on the world's hottest chili pepper. There's this particularly brutal chili pepper-eating contest, and while I was there, I learned that the Indian military had weaponized this chili. They made a nonlethal weapon — kind of a tear gas bomb. So I contacted the Indian Ministry of Defence — one of their science labs — and went over there. And while I was there, just spending time there looking around and seeing what they've been working on — leech repellent, [for example]. Another lab was looking at some swami that had claimed to had never eaten in13 years. And they were like, "What if we study his physiology? Maybe this would be helpful when troops are in remote areas and there's no food." And I was like: wow, military science is pretty esoteric and pretty interesting and [there's] kind of Mary Roach potential there. So that's where I got the notion to look into it.

Live Science: I'm going to quote you from the book here: "Surprising, occasionally game-changing things happen when flights of unorthodox thinking collide with large, abiding research budgets." Did you find that in the military there was this wealth of really interesting, sometimes verging on weird, projects that people were working on?

Roach: Yes. When I started the project, I thought I'd be spending a tremendous amount of time with DARPA. DARPA is kind of the outside-of-the-box thinkers, and I would read papers about ways you could modify the human body to make a more effective soldier, like surgically installed gills for swimming underwater or unihemispheric sleep, where one part of the brain would be awake and the other part would be asleep. And I thought that's really out there if they're doing this, but they're not. It's so futuristic. They write papers about it and, for example, with the unihemispheric sleep, there are some ducks and geese and some marine mammals that sleep with half the brain at the time, so they can be awake, because in the case of the free males, they can breed while they're sleeping. So, they fund research in basic science in that area with the hope that maybe there will be some discovery that might lead to something, but it's very futuristic, and I like to find things where it's happening now and I can go to a lab and see it, experience it and smell it. [Humanoid Robots to Flying Cars: 10 Coolest DARPA Projects]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science: You spent some time talking about transplants in the book, especially penis transplants. The first penis transplant happened recently in the U.S., but it was performed by a different team of doctors than the ones you spoke to. Did the researchers in the book get in touch with you again after that happened?

Roach: Yeah, I've been keeping in touch with Dr. Rick Redett [director of the Facial Paralysis & Pain Treatment Center at The Johns Hopkins Hospital] just because I wanted to be able to provide people with an update when the book came out and I went on tour. They have a patient selected. He is a veteran. I can't remember if it's Afghanistan or Iraq — probably Afghanistan. So, they have a recipient but they don't have a donor. They didn't have a good match for a donor. So they're still waiting. It could happen any day. I think they're ready to go, but the folks at [Massachusetts General Hospital] got there first.

Live Science: With all the people you spoke to, and all the research you did, what did you learn about why it's so challenging — or even if it's possible — to do a whole-body transplant?

Roach: Essentially you'd be taking not just one organ or one limb, but taking a whole body and giving someone a whole new body. And the reason is that, with the example of the penis transplant, it's two major nerves that they're hooking up. Or with a limb transplant, the peripheral nerves, it's just like a telephone cable, and when you cut it, and reattach it, it's a fairly straight process for the nerve to regrow in its new home. When you're talking about spinal nerves or an eye, it's not a phone cable. The analogy is more like a computer system, and the body doesn't know what to reattach where. It's way too complex.

Plus, it's just such a massive — the more different types of tissues in the transplant, the more opportunities for rejection and the immune system saying, "No, this is foreign. I don't want it." With [hand and face transplants], there are a lot more rejection issues than with a liver, say. It just amps up the level of complication. And those are just the basics. I'm sure there are a dozen other things that are problematic in trying to hook up an entire body.

Live Science: Another thing that I never thought was such an issue for the military is diarrhea. You spend a whole chapter on this topic. How did you find out it was such a big problem, and how did you end up going in that direction?

Roach: That came about because someone at the Mayo Clinic Research center, the public affairs person, she would send me little summaries of what's going on in all these different units. And there was one that talked about the work of this one Navy captain who was looking at diarrhea. Like you, I kind of went: huh? Diarrhea? But of course, since I covered extreme constipation in "Gulp" [a 2013 book by Roach about the alimentary canal], it seemed like a natural follow-up to that. I can't not write about diarrhea, that would be unthinkable. So I contacted the researchers and as it turns out, they were heading off to Djibouti to work on this project called TrEAT TD, and they were looking at a faster treatment regimen for traveler's diarrhea, which can be pretty extreme. Depending on what pathogen you have, it can really take you out of commission. And he said, "Sure you can travel all the way to Djibouti to talk about diarrhea, if you can get approval." Thus began this two-week frenzy of emails flying back and forth. No one was saying "no," but none of them had the authority to say "yes" and they didn't know who did, because they don't often get a request to have someone go into Camp Lemonnier to write about diarrhea. [Top 7 Germs in Food that Make You Sick]

Live Science: As I was going through the book, it occurred to me that there are some ties back to your previous work, like you mentioned with "Gulp" and also with some of the cadaver studies that you mentioned. How much did your previous work help or inspire what was going on in "Grunt?"

Roach: I guess I have a fairly predictable range of curiosities. "Stiff" has always been my most popular book. It's the one most people have heard of and/or read over the years. I get a lot of notes from people asking, "When are you going to do a Stiff 2?" Or if I'm going to do a follow-up. And now, I don't want to do another whole cadaver book, but I know that was a popular book, so when I came upon a cadaver study — and there were two, coincidentally, in this book, of course I jumped at the opportunity, because I'm Mary Roach and if there's a cadaver within 100 miles, I've got to be there.

Live Science: Another somewhat surprising thing that seemed very classic Mary Roach was the maggot therapy that was discussed in this book.

Roach: Again, yes! It's funny because people wonder why I'm so obsessed or interested in these things that I come back to them. It isn't so much that. It's just these were the things that seemed to be popular with my readers, and I'm writing books for my readers, so I kind of feel like I'm giving you people what you want! It's not that I'm a weird person, I'm very normal. (laughs)

But I like the things that fall through the cracks, and the things that other people turn away from and don't really cover. I like to explore those because once you start to look into them, they stop being simply gross, and they become fascinating. A maggot is an amazing little eating machine. It breathes through its butt and it eats nonstop, preparing for this very weird, sci-fi transformation into a fly. It's so weird. Maggots, when you peel away the maggoty-ness of them, are really interesting. So, I'm trying to share that kind of sense of wonder and curiosity.

Live Science: And this wasn't just one person experimenting with maggots. This is something that is actually done in some hospitals.

Roach: Oh, yeah, the maggot is an FDA-approved medical device. You have to have a prescription for maggots, and there's a proper dosage. There's a company that raises them, packages them and ships them out, along with a little maggot cage dressing that keeps them on the wound and not crawling all over our home. So, yes, there's an industry. It's mostly for foot ulcers in diabetics — they don't heal well, or at all, sometimes. And rather than heading into an amputation scenario, maggot therapy has been really effective in those folks. So those folks are big fans of maggots. [Ear Maggots and Brain Amoebas: 5 Creepy Flesh-Eating Critters]

Live Science: I also wanted to talk to you about the chapter on the stink bomb, because this seemed like a strange part of World War II history. How serious did this research get? Did it actually get to the point where these were being deployed?

Roach: They were not deployed, but it was two years [of research]. There's a big fat file in the archives of the OSS [the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency], and there were two years of coming up with some of the worst possible combinations of smelling compounds. And then they had to figure out deployment of this little nonlethal weapon. They had a lot of problems with backfire: you squeezed the tube and it would spray backwards and get all over you, the operator. It was something to be handed out to groups in occupied countries in World War II. Motivated citizens would sneak up behind a German officer, and spray his shirt of jacket with this, and he would stink, be humiliated and his morale would be weakened. It was a very subtle, bizarre approach.

It just doesn't seem like it would have merited so much time and money, but it did. And then, ironically, the final report was issued 17 days before the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, so there wasn't any call anymore for the stink paste. The same groups were involved with the stink paste and the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima, so it's a weird, very strange chapter of military history right there. [10 Epic Battles that Changed History]

Live Science: Did you get a chance to smell any of the scents that they were working with?

Roach: I did. I smelled that very item. The odors may have shifted and broken down somewhat. It was a very — to me, it wasn't a fecal smell, which was the original design plan. They wanted to make it smell like you pooped yourself. The nickname was "Who Me?" As in, "Not me, I didn't do it." It doesn't smell like that at all. It's kind of sulfur-y, onion-y, kind of prickly. It's bad smelling but not like a latrine or anything like that. It seems to have morphed quite a way from the original intent of Stanley Lovell, the guy at the OSS.

Live Science: Each of the chapters in the book felt like its own little mini book. Were there things that you wanted to include but they had to be left out?

Roach: Yeah, I had a lot of false starts. I wanted to embed. It was approved by the U.S. military but ISAF, the group that is part of the coalition body, which is higher than the U.S., they didn't support the embed, because it was during the drawdown in Afghanistan. They were just doing very few embeds because they're expensive and a pain.

And I had wanted to cover "Care in the Air." I wanted to cover medevac and planes or helicopters that are outfitted for medical procedures — to actually be on board when something like that is happening, which would have meant significant time invested because, at that point, there were thankfully very few medevacs of U.S. personnel. So, the timing was not good for it, and also the embed wasn't approved.

I also wanted to write about the Army blood program. Blood is a perishable item, so how do you make sure you have enough where you need it? And how do you get it to these sometimes remote areas? The Army has a whole network in place for doing that, and I was going to include a chapter on that. But again, I couldn't sort of get inside that world. I wouldn't necessarily have to embed, but I would have to get myself there, and this was logistically not working out, and there wasn't much call for — they call them "vampire flights," when they're getting blood where it's needed — they weren't really doing that anymore because there were so many fewer injuries.

Live Science: The last thing I wanted to ask you about is the humor in your writing, because you weave it so deftly throughout the book, and even when you're talking about some very serious topics. Is humor something you actively think about while you're writing?

Roach: I think about it more in the planning stages of a book, because it totally depends on the material. Particularly with this book, there are just things that aren't going to lend themselves to humor. It's not appropriate and it doesn't even suggest itself as an option. The "Who Me?" chapter, I wanted to include it anyway, but it was an opportunity to have a little fun, because in the correspondence back and forth, some of the problems they were having with this stink paste, it was hilarious. Historical elements are a little safer and then also I try to poke fun at myself as this clueless outsider, which I so very much was in this book. It's a culture I'm not familiar with. So I'm just bumbling around as a stupid outsider, so some of the humor comes from that.

So in choosing the content of the book, I definitely have that in the back of my head. Would this be something that would make for an entertaining, fun read? And I like to have some of that in the book. And sometimes it's footnotes. Footnotes are a little removed form the narrative, and those can be funny and, hopefully, not too jarring with the tone of the rest of it.

Original article on Live Science.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.