Fish Can Recognize and Remember Human Faces

A wee-brained tropical fish can distinguish between human faces in a lineup, researchers have found. This is the first time such an ability has been shown in fish.

Recognizing human faces is a difficult task. Because nearly all human faces have the same basic attributes, recognizing a face requires distinguishing subtle differences in facial features, said Cait Newport, a zoologist and Marie Curie research fellow at the University of Oxford.

In fact, past research has shown that a select few animals — including horses, cows, dogs and even some birds, such as pigeons — can successfully complete such a task. All of those animals, however, have a neocortex, or neocortex-like structures. The neocortex is a part of the brain that contains a visual-processing region as well as the fusiform gyrus, which is thought to be heavily involved in facial processing, the researchers noted. [Video: Watch Archerfish Squirt Water at Images of Human Faces]

"Most animals tested possess a neocortex and have been domesticated, and may, as a result, have experienced evolutionary pressure to recognize their human [caregivers]," Newport and her colleagues wrote in today's (June 7) issue of the journal Scientific Reports.

How to train a fish

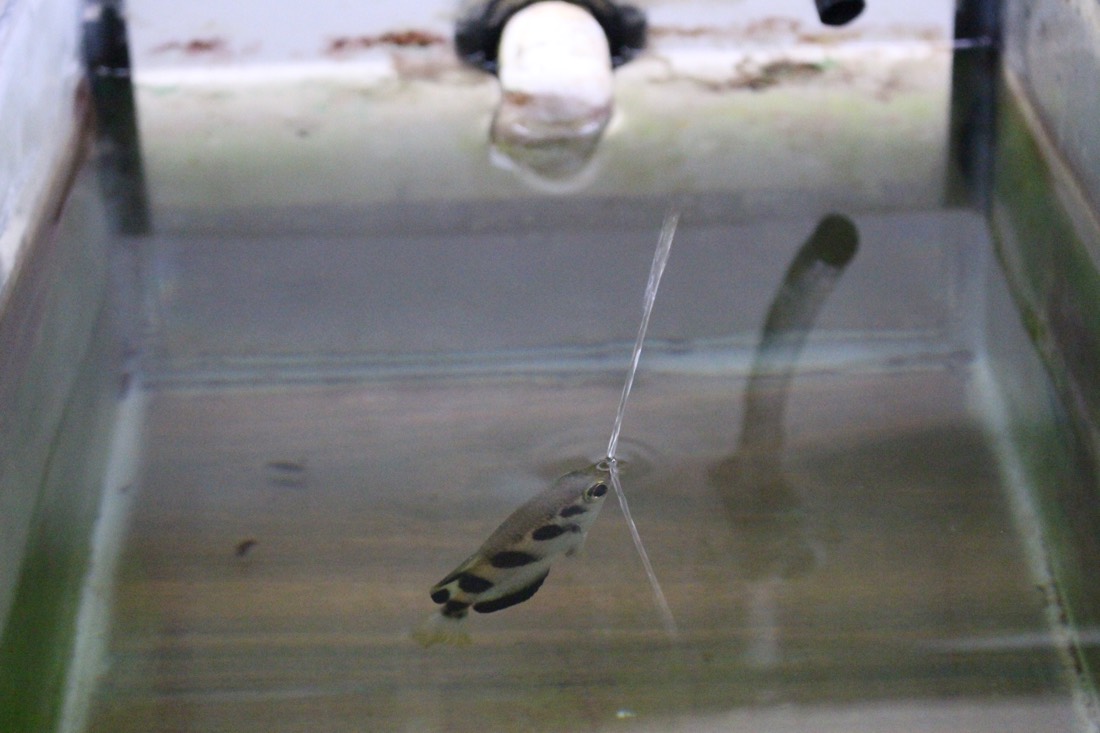

To see whether an animal with a simpler brain — one lacking a neocortex — could recognize faces, the researchers turned to archerfish (Toxotes chatareus). This species is known for relying on vision to detect flying land animals, such as insects, and proceeding to spit jets of water at the aerial prey to knock it down, the researchers wrote.

Newport and her colleagues trained archerfish to select the "correct" image of a human face on a computer screen above their aquarium; for this fish, spitting a jet of water at an image is akin to pointing at it.

"It takes time to train fish, and it can be a bit of an art; but it is not as difficult as you might think," Newport told Live Science. "It is very similar, in fact, to training a dog. You can train a dog to sit by giving it a biscuit every time it sits. Similarly, the fish naturally spit at things in their environment, and we reinforce this natural behavior by feeding them when they hit the image we want."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the learned human face was placed in a lineup of 44 unfamiliar faces, the fish spit at the correct face 81 percent of the time, on average. Even when the researchers standardized more obvious facial features, such as head shape, and used black-and-white images, the archerfish showed accurate squirting about 86 percent of the time.

Smart fish?

The finding suggests that a sophisticated brain isn't needed to recognize human faces, the researchers said.

Even so, the fish likely didn't process these human faces the same way a human would, Newport said.

"When humans recognize a human face, it provides not only information about the identity of the person but also a whole host of other information, such as a person’s gender, age, health," Newport said. "It is unlikely that the fish are gathering the same information. Instead, they are likely just learning this complex pattern-discrimination task."

The fish might not have been gathering complex facial information, but their little brains were discriminating complex patterns.

"Because they were able to distinguish one face from so many others, it means they had to use relatively complex features of the faces as cues," Newport said.

Moreover, they could remember those faces. "The fact that we are able to train the fish shows that they have an impressive memory for detailed images and that these memories last much more than 3 seconds," Newport added.

Original article on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.