The seabed holds some fascinating historical secrets, but unlike monuments on land, they’re largely hidden from view. Now, archaeologists in the United Kingdom are using 3D printing to bring two historical shipwrecks to life for history enthusiasts and experts alike.

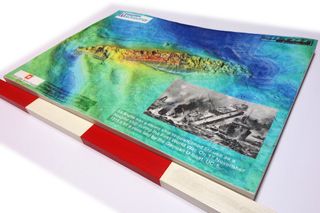

Using data from photogrammetry (measuring the distance between objects from photographs) and sonar imaging, the researchers have produced scale models of a 17th-century shipwreck near Drumbeg, in Scotland, and the remains of the HMHS Anglia, a steamship that was used as a floating hospital during World War I. The steamship was sunk by a mine off the south coast of England.

"It was a proof of concept for us, trying to establish what could be done using sound and light, but there are so many different applications you could use this for," said maritime archaeologist John McCarthy, a project manager at Wessex Archaeology who carried out dives at the Scottish site and was in charge of producing the 3D models. [Photos: Shipwrecks of the Deep Sea]

"People can engage much more easily with a physical object in front of them. You can bring it to schools and conferences, and we are hoping to donate both models to local museums, once we've finished with them," McCarthy told Live Science.

It was not particularly difficult to create 3D-printed representations of the shipwrecks, McCarthy said. The magic, he said, was in creating the virtual models that were fed into the 3D printer.

McCarthy carried out initial experimental surveys of the Drumbeg wreck in 2012 with his colleague Jonathan Benjamin, who is now a lecturer at Flinders University in Australia. McCarthy recently joined him there to begin Ph.D. studies under Benjamin's supervision.

At the Drumbeg wreck site, the pair found three heavily encrusted cannons with evidence of a preserved wooden hull underneath. The ship's identity is still unknown, but one theory holds that it is a Dutch trading vessel called the Crowned Raven, which is known to have been lost in the bay in the late 1600s.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After realizing the techniques they were using could provide enough data for a 3D model, the archaeologists went back to do a more detailed survey in 2014 and used the lessons they had learned from their first attempt.

The archaeologists used a technique called photogrammetry, which involves taking hundreds of overlapping photographs of a site and then feeding them into a computer program that can stitch them together. The application is able to establish the spatial relationships between photos, which allows it to create a so-called 3D point cloud that maps each image in 3D space.

"Once you have a point cloud, you can turn it into a solid surface," McCarthy said. "Then you have a 3D model of the site that's not subjective or an artist's impression, but entirely objective."

The benefits of photogrammetry are that it produces very high-resolution images and it can capture the true color of the site, McCarthy said. The method is easily thwarted, however, by excess marine growth or poor visibility, and it is not well-suited to covering large areas.

Sonar, on the other hand, can see through the murk and can cover much larger areas, McCarthy said. For the 329-foot-long (100 meters) HMHS Anglia, another team from Wessex Archaeology used multibeam sonar — which operates in a similar way to a laser scanner — to do a much larger survey of the shipwreck site.

While multibeam sonar can't match the subcentimeter resolution of photogrammetry, using higher-end equipment and doing many passes can boost accuracy, McCarthy said. The Anglia survey was a particularly high-resolution one, he added, which was part of the reason it was selected for the 3D printing project.

McCarthy pointed out that the Wessex Archaeology team is not the first to create 3D-printed models from underwater imaging data. He said that the field has been booming in recent years, with big advances in both sonar and photographic techniques, and even some novel laser-scanning approaches are beginning to come through.

"All maritime archaeologists are engaging heavily with these techniques now," McCarthy said. "Advances in hardware and software in the last five years has allowed us to do very rapid and cheap surveys, and it has added to the tools we use underwater."

Original article on Live Science.