ISIS Plays 'Evolutionary Game' to Avoid Online Shutdown

Researchers have created a computer model to figure out the savvy ways that the terrorist group called ISIS has managed to grow its members online. The results could help to thwart future attacks.

The researchers identified three behavioral patterns of online ISIS supporters that allowed the groups to adapt and evade moderators, leading to the unchecked growth of the organization.

"We were interested in how support for particular extreme ideas or extreme organizations develops online, and then if we could understand that, what the implications would be for then what happens in the real world," study researcher and physicist Neil Johnson of the University of Miami told Live Science.

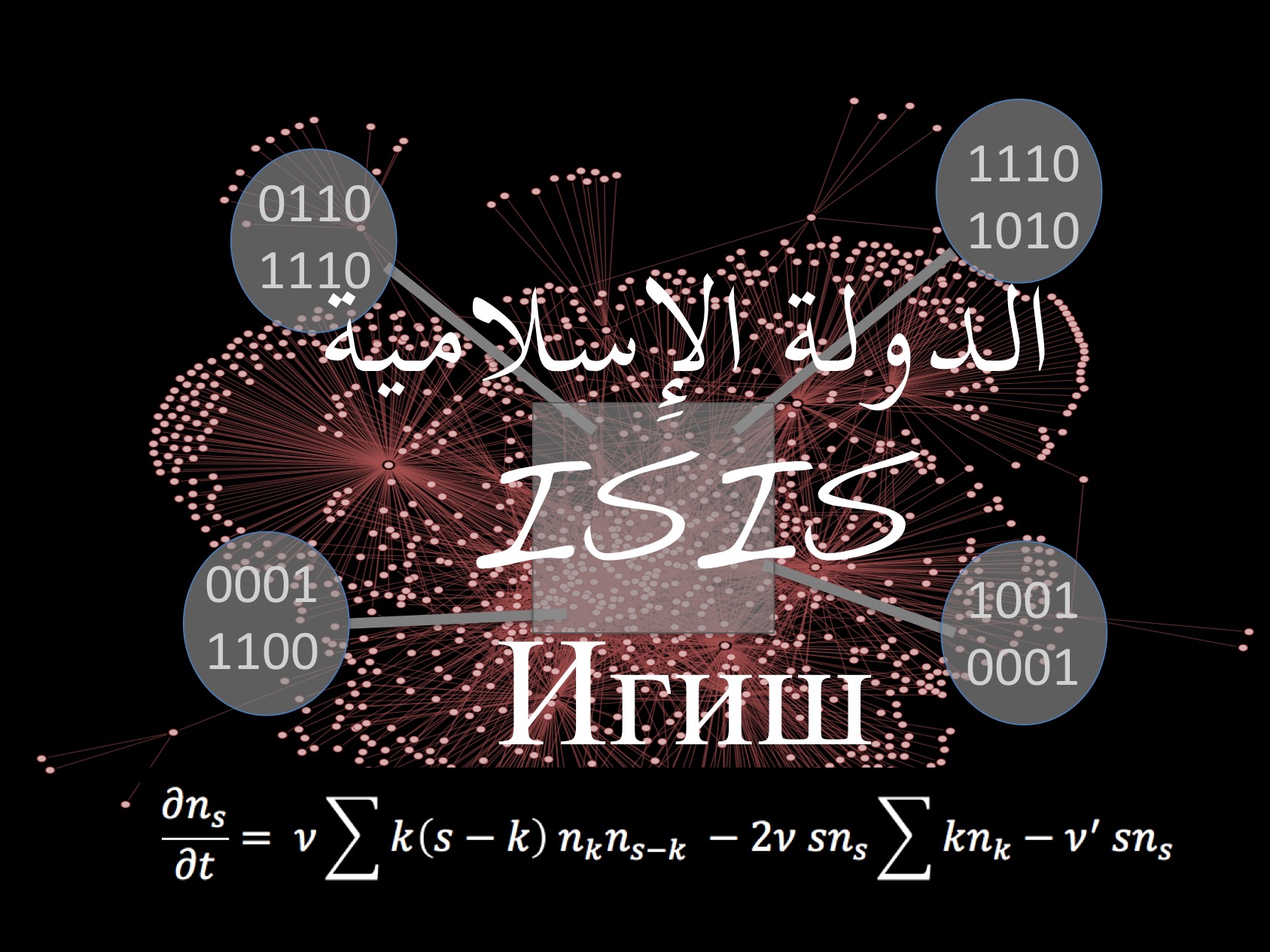

In the new research, published today (June 16) in the journal Science, Johnson and his colleagues identified and studied 196 pro-ISIS aggregates, ad hoc online groups formed via linkage to a social media page. The groups were created through VK.com (originally VKontakte), the largest social networking service in Europe. [Science of Terrorism: 10 Effects of 9/11 Attacks]

The researchers found that though the pro-ISIS groups consisted of members who have likely never met and have no direct way of contacting one another, the aggregates were able to mutate and reincarnate to avoid detection.

These aggregates are careful in their adaptations, not taking too long to reappear and not changing their identity too drastically, the researchers said. They can change enough to evade "cyberpolice" — computer and human moderators seeking to shut the groups down — but not so much that the followers are lost.

"Individual aggregates are able to adapt and mutate in, we found, three ways — I'm sure there are more by now — in which they manage to evade [moderators] or at least prolong their lifetimes and also grow bigger, quicker," Johnson said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The groups would adapt by changing their name. There was also visibility-to-invisibility kind of switching, changing the content from being open to any VK.com user to being open only to current followers of the aggregate. Reincarnation was the third adaptation tactic, where an aggregate disappears completely and then reemerges with a new identity but with most (>60%) of the same followers.

What is notable in these adaptions is that these are not coordinated changes, Johnson said. There is no post or phone call declaring the need to change, the time or place, or the new name.

"We found they play this clever kind of evolutionary game," said Johnson, who models human organization and conflict.

When the scientists looked at online groups of civil protestors, which the researchers used as sort of a control or baseline for comparisons, they didn't see this same adaptive ability. The researchers hypothesized that the pro-ISIS groups continuously changed because of pressures from moderators trying to shut them down.

Based on the research and models, mathematically, Johnson told Science magazine anti-ISIS organizations could take out large groups by targeting groups 10 percent of the larger group’s size.

Large pro-ISIS aggregates grow as the result of smaller groups coming together. If countermeasures of anti-ISIS agencies cannot stop this development, the study authors wrote in Science, "then pro-ISIS support will grow exponentially fast into one superaggregate."

Johnson said that in his group's research and modeling, the focus was not to just make predictions but to understand the pro-ISIS online world.

"In this kind of hidden inner core, people or followers attached in these aggregates are changing over time, but as they evolve, they're also sharing potentially important information, operational details," Johnson said. For instance, in one case, the followers were sharing images of drones to watch out for in case of drone strikes.

Since the study was completed last year, Johnson estimated that in the past six months many aggregates have had to adapt again, possibly away from VK.com and onto the dark net.

"It's a little bit like fish when they form shoals and the shoals merge and break up, and when a predator comes in they scatter and then they reform," Johnson said. "But they tend not to reform around where the predator was. They'll go off into different corners and gradually build up again.

"It's not too dissimilar," he added, "But, of course, now it's on the internet."

Original article on Live Science.