Ancient Greek Naval Base Held Hundreds of Warships

Thousands of years ago in a bustling port near Athens, Greece, a massive structure housed hundreds of warships that likely took part in a pivotal Greek victory against the Persian Empire.

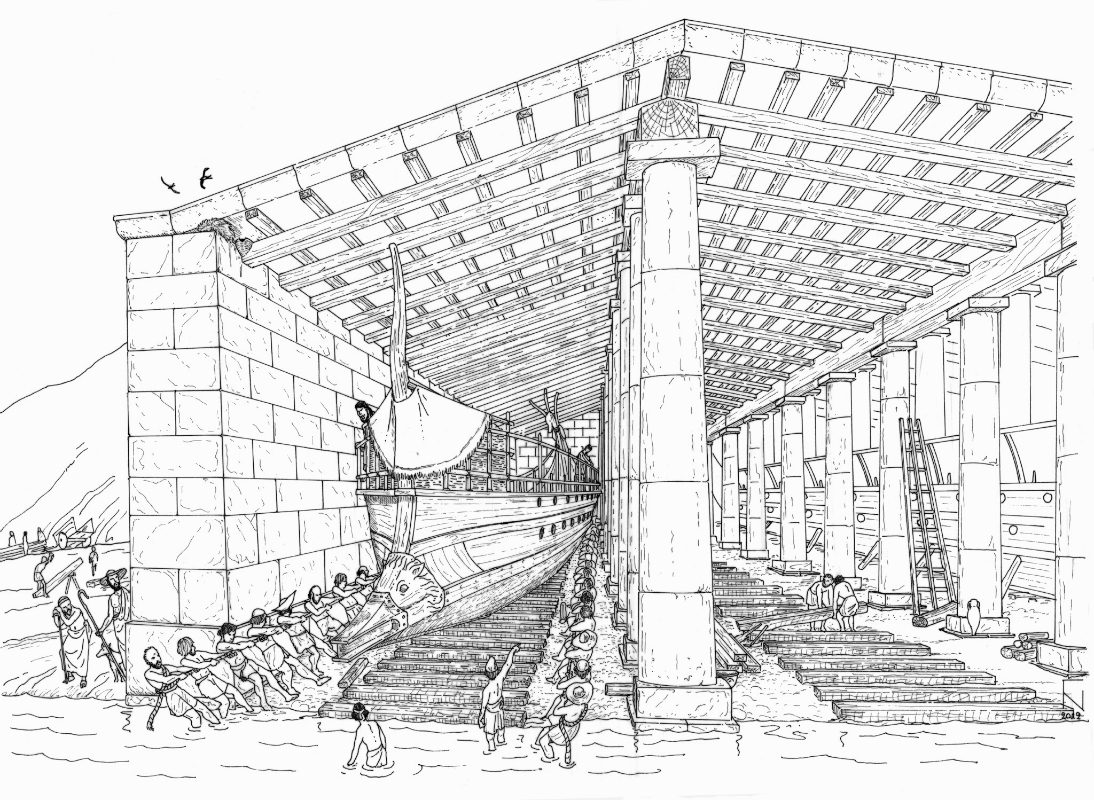

The ships, named "triremes" for their three rows of oars, are long gone. But underwater archaeologists who spent more than a decade excavating the site where they once rested found remnants of the so-called "ship sheds" that protected the boats, part of an enormous and fortified naval stronghold beneath what is now the Mounichia fishing and yachting harbor.

This shipyard complex is one of the largest known structures in the ancient world, according to a statement by the Carlsburg Foundation, which contributed funding toward the archaeological excavation. [In Photos: Amazing Ruins of the Ancient World]

Protecting the fleet

Divers uncovered six sheds, which lead archaeologist Bjørn Lovén described in a statement as "monumental." According to Lovén, an associate professor in maritime and classical archaeology at the University of Copenhagen, each of the sheds measure 23 to 25 feet (7 to 8 meters) high, and 164 feet (50 m) long. The structures protected the war vessels against shipworm, a marine mollusk pest that burrows into wood, and kept the ships from drying out and warping.

Lovén's work was part of the Zea Harbour Project, a series of excavation efforts on land and sea that began in 2001 and ended in 2012. It investigated two ancient Greek harbor areas — Zea and Mounichia — in the Piraeus port city, uncovering and documenting the area's ancient naval bases. At Mounichia, researchers focused on regions inside and outside the harbor basin, according to the project website.

Contaminated waters

Modern harbor waters are typically highly polluted, and Mounichia was no exception. According to the project website, divers required specialized procedures and equipment designed for working in tainted water, and wore multiple layers to minimize exposure to pollutants. All equipment had to be washed and decontaminated after each dive day — as did the divers.

And visibility was very poor — most of the time, the archaeologists working underwater couldn't see more than 8 inches (20 centimeters) in front of them, Lovén said in the statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Despite the challenging conditions, divers not only excavated and mapped the long-lost shipyard, but also recovered pottery shards and fragments of wood from a colonnade's foundation that dates from between 520 and 480 B.C. According to Lovén, this suggests that at least some of the ships sheltering there were part of the Athenian fleet that defeated the Persian army during the Battle of Salamis in 480 B.C. — a pivotal moment in Greek history.

"A Persian victory would have had immense consequences for subsequent cultural and social developments in Europe," Lovén said in the statement. "The victory at Salamis rightly echoes through history and awakens awe and inspiration around the world today."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.