AI Boosts Cancer Screens to Nearly 100 Percent Accuracy

Diagnosing cancer is about to get more accurate, with the help of artificial intelligence.

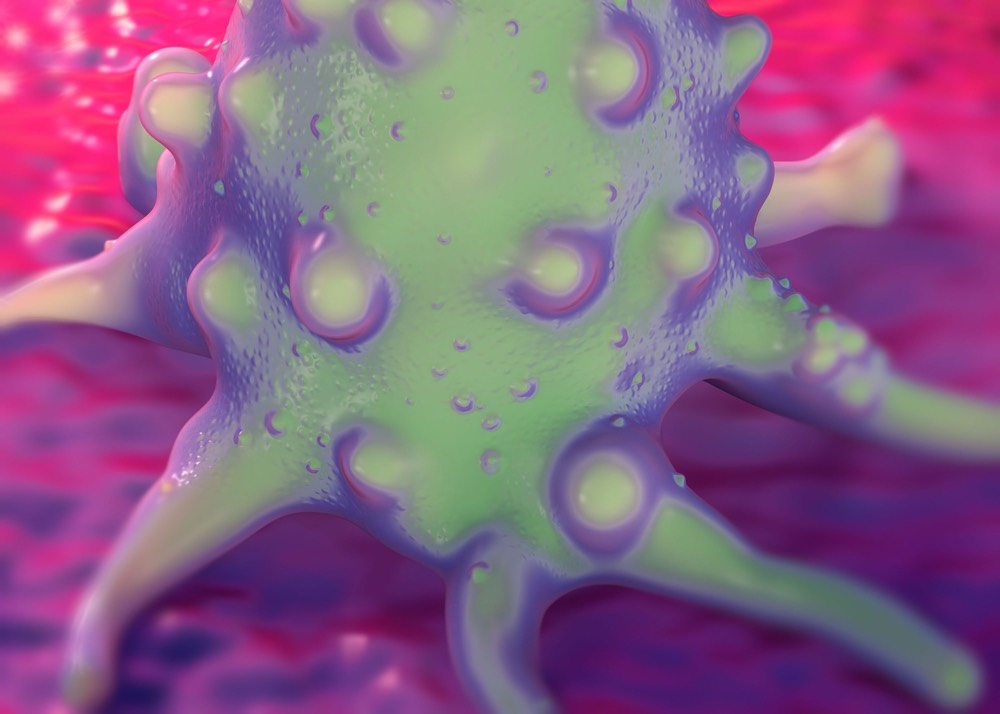

Pathologists have diagnosed diseases in more or less the same way for the past 100 years, by laboring over a microscope reviewing biopsy samples on little glass slides. Working almost robotically, they sift through millions of normal cells to identify just a few diseased ones. The task is tedious and prone to human error.

But now, scientists and engineers have created a technique that uses artificial intelligence (AI) and can differentiate cancer cells from normal cells almost as well as a top-notch pathologist. A Harvard-based team demonstrated the AI method as part of a competition at the 2016 International Symposium of Biomedical Imaging in Prague, showing how it could pinpoint, with 92 percent accuracy,cancer cells among samples of breast tissue cells. That accuracy was far better than the other AI methods in the competition, landing the team first place.

Humans + AI

Humans still have the edge: Pathologists beat the robots in this competition with their ability to identify 96 percent of the biopsy samples with cancer cells. [Super-Intelligent Machines: 7 Robotic Futures]

But the real surprise came when pathologists were teamed up with the Harvard team's AI. Together, the artificial intelligence and good, ole human intelligence identified 99.5 percent of the cancerous biopsies.

While the thought of trusting Dr. Robot with your medical analysis may seem a bit scary, some scientists see great promise in AI-assisted doctor services.

"Our guiding hypothesis is that 'AI plus pathologist' will be superior to pathologist alone," said Dr. Andrew Beck, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School in Boston, who led the creation of the winning AI design. "If we and the larger research community are able to demonstrate that the use of AI tools significantly reduces diagnostic errors, I believe patients, physicians, health care payers and health systems will be supportive of the addition of AI tools in the clinical workflow," he told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Why breast cancer cells?

The contest, held in April, invited AI designs from around the world created by private companies and academic research organizations. The goal was to spur interest in creating more accurate AI methods of disease diagnosis.

"The fact that computers [in the April competition] had almost comparable performance to humans is way beyond what I had anticipated," said Jeroen van der Laak of Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands, who organized the contest. "It is a clear indication that artificial intelligence is going to shape the way we deal with histopathological images in years to come." [Infographic: The History of Artificial Intelligence (AI)]

The contest organizers chose the topic of breast cancer detection — more specifically, metastatic cancer cells in sentinel lymph node biopsies — as a real-world test of an important public health issue. Among U.S. women, breast cancer is the second most common type of cancer (after skin cancer) and the second deadliest type of cancer (after lung cancer), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A sentinel lymph node biopsy is a surgical procedure in which a sample of tissue is removed from a sentinel node, the first in a group of lymph nodes, or glands, where cancer cells might spread after leaving the original site. A multicenter study published in 2003 in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons found that these biopsies, using traditional human analysis, were 96-percent accurate, with a false-negative rate of 8 percent.

Because cancer surgeons rely on the biopsies to decide what tissue to remove or leave in place, often at the very moment a cancer is beginning to spread, accuracy in the biopsy analysis is crucial.

Machines that learn

Beck's group used a process called "deep learning" to essentially teach a computer to better recognize what cancer cells look like. This process is a machine-learning algorithm used in applications such as speech recognition; it makes the system more and more accurate with each use. In preparation for the contest, Beck's group fed the computer thousands of images of cancer cells.

The team identified examples for which the computer was prone to make a mistake in cancer identification and retrained the computer using greater numbers of more difficult examples.

The development of such automated diagnostics has been a goal for the AI field for the past 30 years, as computers became more commonplace in labs, Beck said. But only recently has the field seen the improvements in scanning, storage, computational power and algorithms necessary to make this possible.

Don't worry, pathologists won't be fading away. Beck said the field will evolve to adopt new skill sets. For example, pitfalls to avoid with AI include a system that routinely misses a particular rare form of cancer the AI hasn't seen before or that is routinely thrown off by an artifact in the biopsy image, he said. Humans will be needed to continuously teach the robots.

Beck's team includes postdocs in his Harvard lab, Dayong Wang and Humayun Irshad, along with Harvard graduate student Rishab Gargya and MIT researcher Aditya Khosla. A technical report describing this work was posted yesterday (June 20) on the open-access e-print archive arXiv.org.

Follow Christopher Wanjek @wanjek for daily tweets on health and science with a humorous edge. Wanjek is the author of "Food at Work" and "Bad Medicine." His column, Bad Medicine, appears regularly on Live Science.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus