Mummified, 99-Million-Year-Old Wings Caught in Amber

About 99 million years ago, a hummingbird-size bird likely fought for its life after getting stuck in a glob of tree resin, but it couldn't tear itself away and eventually died, leaving its feathers to mummify in what became a lump of amber, a new study finds.

The soft resin even captured evidence of the bird's wriggling and writhing in an effort to free itself.

"There appear to be claw marks in the resin, which would suggest a struggle," said co-lead study researcher Ryan McKellar, a curator of invertebrate paleontology at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Canada. [See Images of the Mummified Bird Wings]

Another preserved wing found in the clump of amber "appears to be a severed limb that may have been torn off by a predator, or may have floated free from the rest of the corpse due to resin flows," McKellar told Live Science in an email. "The broken end of the bone is fully encapsulated in amber."

Both wing fragments are only a few centimeters in length, and are likely from the same species of ancient bird, the researchers said. Moreover, the findings are the first concrete examples of follicles, feather tracts and bare skin from Cretaceous period birds, they said.

Lida Xing, the study's other co-leader and a lecturer at the China University of Geosciences in Beijing, discovered the specimens at an amber market in Kachin State, Myanmar, in 2015. Delighted at the find, the researchers got right to work, studying the mummified feathers with microscopes and X-ray micro-computed tomography (CT) scanning — a technique that's similar to a medical CT scanner but with more magnification power — to see the underlying tissue and bones, McKellar said.

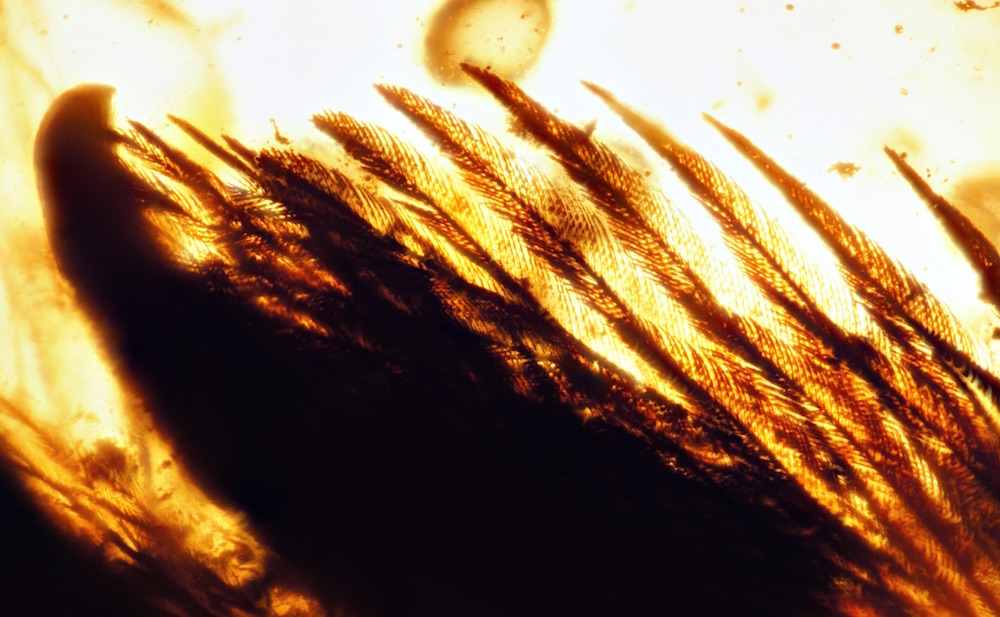

"The work with microscopes under a wide range of lighting conditions allowed us to examine the feathers, claws and skin — seeing minute details of the feathers and their pigmentation," McKellar said. Ultraviolet (UV) light also helped them see flow lines within the amber, indicating how the tree resin moved before it solidified, and figure out how the wings had become trapped, he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Their analyses indicate that the two birds belonged to the enantiornithines, a group of ancient birds that had teeth and whose skeletal anatomy differed within the pectoral girdle and ankle regions from modern birds. Furthermore, the two specimens had adult-like feathers even though they were juveniles, McKellar said.

Most fossilized feathers are compressed, 2D remains preserved in sedimentary rock, making this finding all the more extraordinary, McKellar said. [Image Gallery: Ancient Life Trapped in Amber]

"This is the first time that feathers have been found alongside skeletal material in Mesozoic [dinosaur-age] amber," McKellar said. "We also get to see traces of pigmentation that would not be visible in the more common compression fossils, he added. For example, the researchers noticed "a pale spot and band on the upper surface of the wings, and a pale or white underside of the wings," he said.

This isn't the first time McKellar has studied mummified feathers. In 2011, McKellar and his colleagues published a study in the journal Science on 80-million-year-old feathers preserved in Canadian amber, although outside experts told Live Science that it was unclear whether the specimens were from a bird or a dinosaur.

The new study was published online today (June 28) in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.