Saturn Moon Enceladus' Plumes May Resemble Earth's 'Lost City'

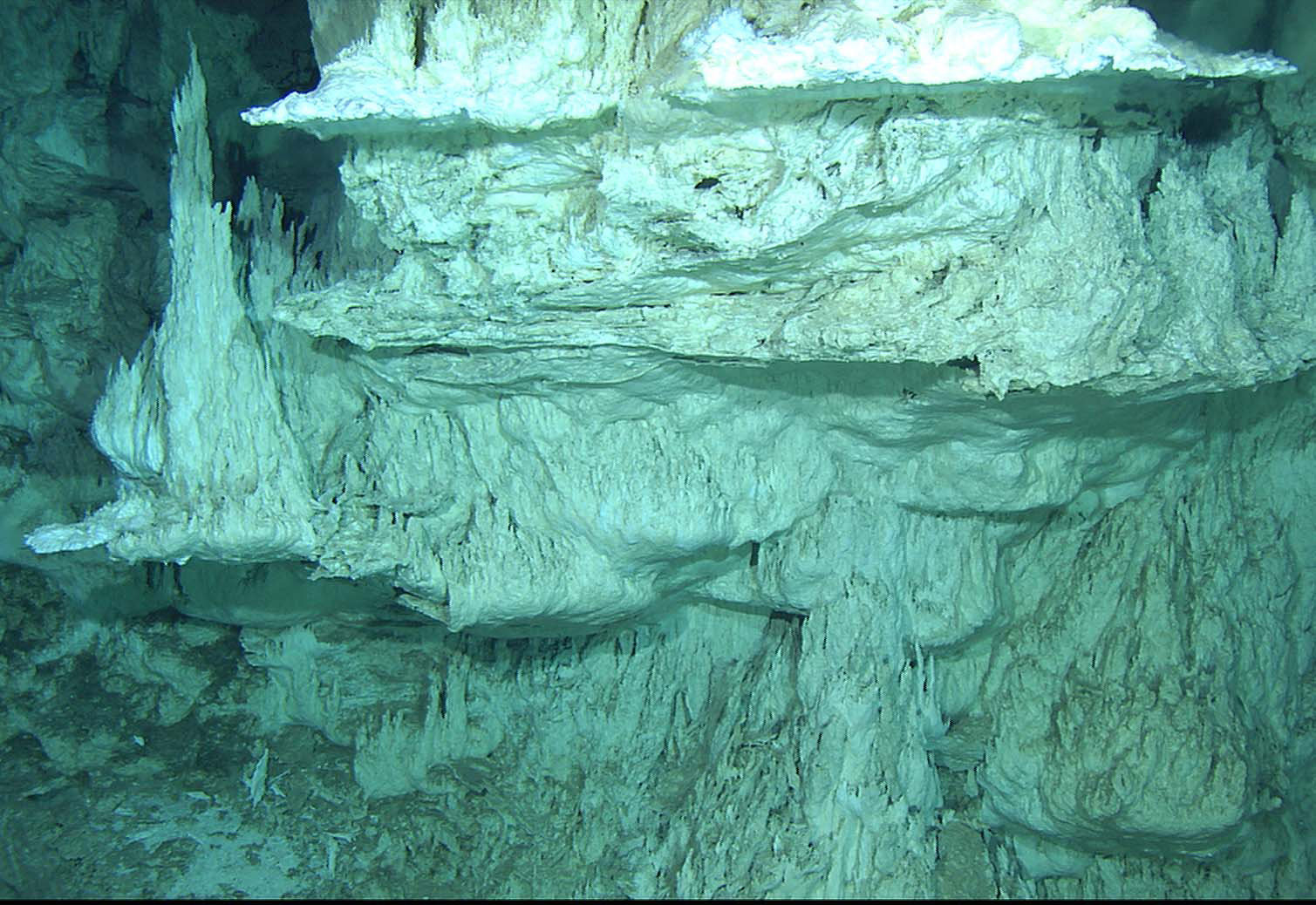

Saturn's intriguing moon Enceladus could resemble Earth's "Lost City," a network of hydrothermal vents in the Atlantic Ocean where life survives despite cold and darkness.

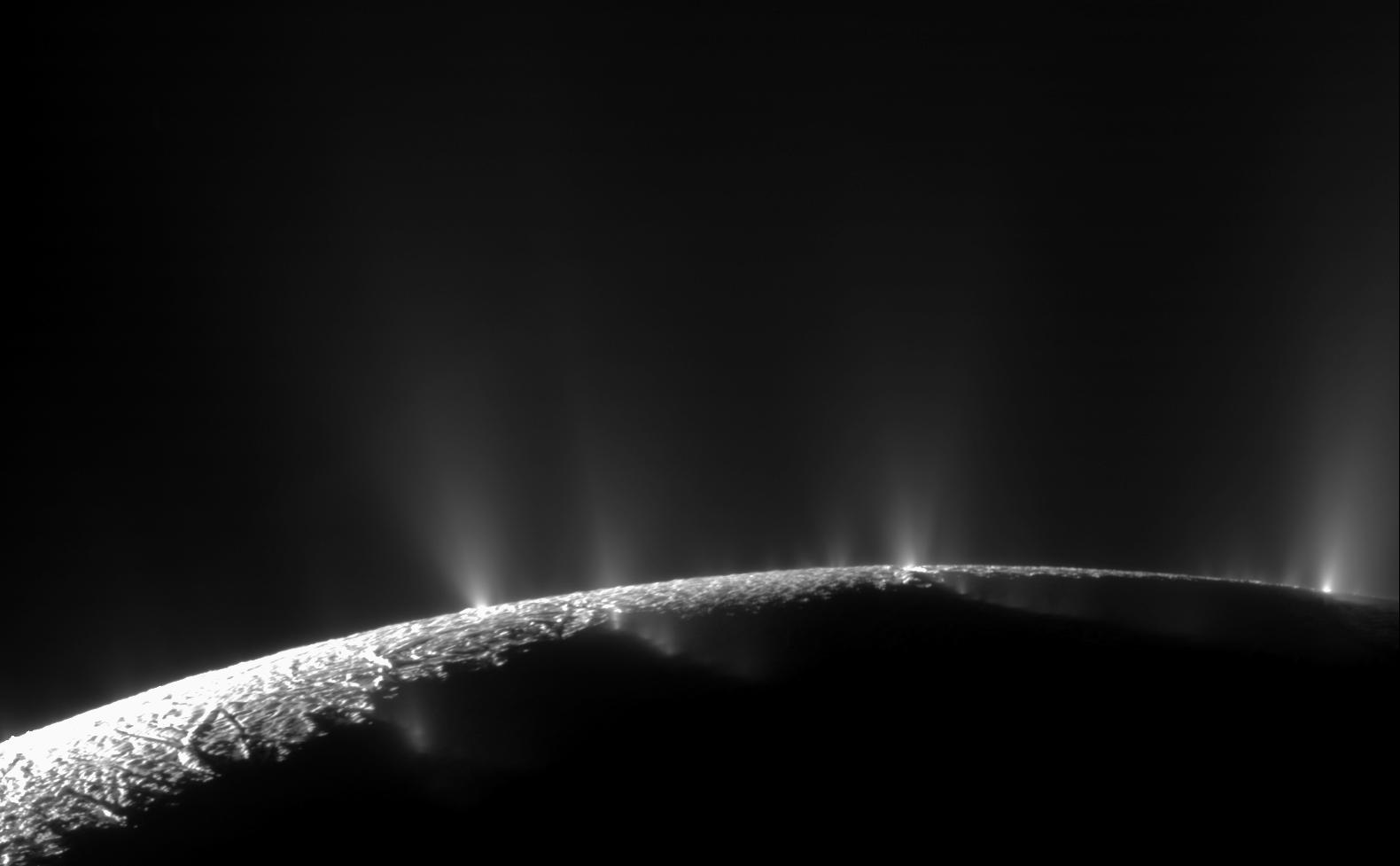

Earth is the only planet in the solar system with liquid water on its surface, but many of the solar system's moons and dwarf planets seem to hide their oceans beneath their crust. Saturn's moon Enceladus, on the other hand, isn't content to keep things underground; large gashes at the moon' south pole spurt liquid from the interior into space. The access provided by these vents makes it a tempting spot for scientists hoping to search for signs of life outside of Earth.

"We want to use chemistry as our guide to looking for signs of life," said Christopher Glein, a research scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Texas. Glein discussed the history of human understanding of Enceladus last month at the 228th American Astronomical Society meeting in San Diego, California. There, he compared that moon's undersea environment to the Lost City hydrothermal field in the Atlantic Ocean, where hot water bursts from the ocean floor and life thrives in the otherwise desolate depths. [Saturn's Geyser Moon Enceladus Amazes in Final Flyby Photos]

"Is there life beyond Earth?" Glein asked. "Our generation is now poised to begin to tackle and search for some answers."

"Candy to life"

When NASA's Voyager 2 mission flew by Enceladus in 1981, it revealed terrains far smoother than the rocky satellites seen before. The polished landscape suggested that something unusual was happening on Enceladus. But it wasn't until NASA's Cassini mission caught a glimpse of plumes spurting from the southern pole that scientists realized just how unusual the moon is. Today, scientists have identified 101 individual jets shooting out from the large "tiger stripe" fissures at the southern pole, which average 80 miles (130 kilometers) long (a significant stretch of the moon's surface).

At first, scientists thought the water feeding the tiger stripes came from a small sea beneath them. In 2015, Cassini's gravitational data revealed that the tiny moon instead housed a global ocean under its entire surface. The bright plumes carried tiny particles of water-ice mixed with water vapor from beneath the surface, Glein said. But the real mystery was what else the stripes might carry.

No one expected Enceladus to spurt samples into space, so Cassini didn't carry any instruments designed to sample the plumes. But the team found a way to use the instruments they did have to study some of the material, and so they guided the spacecraft to dive through the plumes and taste their chemistry.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"What we found was truly remarkable," Glein said.

Cassini discovered salts, which couldn't have come from a slowly melting ice source.

"A liquid ocean that rapidly flash freezes — that does the job," Glein said.

Cassini also revealed that the plumes had a pH of 11.12, making them more basic than acidic. In comparison, Earth's rainwater ranks at 5.6 and seawater around 8. Glein put the plumes' pH in the domain of cleaning agents like Windex.

"It's not quite to drain cleaner, but it's getting there," he said.

One way to raise the pH, and heat the plumes in the process, is the process of serpentinization, which occurs when liquid water reacts with magnesium- and iron-rich minerals. The changed rocks, often green, are loaded with bases, and can lead to a rise in pH, Glein said. Although such rocks are rare on the surface, they can be found tucked away in the mantle or in collections of rocks and minerals on the seafloor.

One of the most famous sites of serpentinization is Earth's Lost City, a collection of hydrothermal vents near the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. First identified in 2000, the vents are heated primarily by the changing rocks rather than by mantle beneath the surface. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, serpentinization can raise temperatures as high as 260 degrees Celsius (550 degrees Fahrenheit), and drives the hydrothermal system of the Lost City.

In addition to providing heat, the Lost City's vents spout methane- and hydrogen-rich fluids to the surface, and are thriving environments for life.

"Hydrogen is like candy to microorganisms," Glein said. And the vents are "just packed with minerals," he added —the combination of chemical, biological and geological processes makes spots like the Lost City vents prime sites for life to have evolved. If Enceladus boasts similar vents powered by a process like serpentinization, life could originate there, as well, Glein said.

The best evidence for vents on the tiny moon comes from farther away, in Saturn's E ring, which is where material ejected from Enceladus can end up. Material from the plumes easily escapes the moon's gravity, which is only 1 percent of Earth's, and falls around the ringed planet. Samples of the ring material revealed silicate particles that scientists traced back to the moon. According to Glein, vents in a subsurface ocean could produce similar silicates.

That doesn't quite cinch the case, though. "We have evidence of hydrothermal vents, but we haven't found the hydrogen yet," Glein said.

The results of Cassini's final deep dive through the plumes are still being analyzed, but Glein said he anticipates submitting the research in the next few months. [NASA Reveals Best-Ever Maps of Saturn's Icy Moons (Photos)]

"One of the great mysteries"

Before Cassini arrived at Saturn, scientists thought Enceladus was too small to maintain water in a liquid state, so the plumes came as a surprise. Exactly how the moon keeps its water liquid remains uncertain.

"There's a serious energy crisis on Enceladus," Glein said, referring to the energy required to keep that water liquid. "It's one of the great mysteries of planetary science moving forward."

Since Cassini first identified the geysers on the small moon, scientists have tried to identify how water remains liquid instead of freezing to ice. One possibility is that the interior of the moon is heated as Saturn tugs and releases it. Another option is that the ocean contains some form of antifreeze, rather than pure water. Chemical reactions between the ocean and the rock, like the serpentinization described above, could also produce the necessary heat.

Enceladus is a tiny moon. With an average radius of 156 miles (252 km), it's only about one-seventh the size of Earth's largest satellite. According to Glein, that makes the moon the smallest geologically active body in the solar system, and the only one to boast water-based cryovolcanism, where icy liquid instead of hot lava oozes from the crust. Coming from such a small world, the eruptions are enormous.

"We don't have volcanic eruptions on Earth that span over an entire Earth diameter," Glein said.

Saturn's satellite is far less dense than the moon or Earth, with roughly half its material consisting of water. Enceledus' icy exterior makes it incredibly reflective.

"If it was our moon, it would be blindingly bright in the sky," Glein said.

The southern hemisphere may not be the only place to ever house plumes, Glein said Geological mapping of the moon's northern latitudes suggests relics of gashes similar to the tiger stripes in the south, he said. As the liquid water freezes, it could close off one set of stripes and open others.

Referring to a famous geyser at Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, he said, "I think Old Faithful has finally met its match in Cold Faithful."

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.