Revenge is a dish best served cold. An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind. My name is Inigo Montoya, you killed my father, prepare to die.

The culture is swimming with depictions of revenge: Sometimes it's deeply satisfying, sometimes it injures the avenger, and sometimes it's a little bit of both.

And it turns out that people's response to vengeance may be just as complicated in real life, new research shows. [Understanding the 10 Most Destructive Human Behaviors]

"We show that people express both positive and negative feelings about revenge, such that revenge isn't bitter, nor sweet, but both," Fade Eadeh, a doctoral candidate in psychological and brain sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, said in a statement. "We love revenge because we punish the offending party and dislike it because it reminds us of their original act."

Urge to punish

A 2012 study in the journal Biology Letters found that people tend to punish others not because of a desire for revenge but because of a sense of fairness. And a 2014 study found that after committing an act of revenge, people feel worse.

But Eadeh wasn't convinced that this could be the whole story. After all, if all revenge does is make people feel bad, why do they seek it out? Even babies believe wrongdoing deserves punishment, according to a 2011 study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"We wondered whether people's intuitions about revenge are actually more accurate than originally anticipated," Eadeh said. "Why is there such a common cultural expectation that revenge feels sweet and satisfying? If revenge makes us feel worse, why did we see so many people cheering in the streets of D.C. and New York after the announcement of [Osama] bin Laden's death?"

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

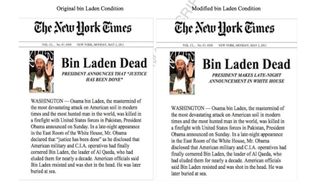

To understand how vengeance affects people, Eadeh and his colleagues conducted three different experiments with 200 participants each. The volunteers filled out a survey about their mood and emotional responses after reading either a New York Times article with the words "Justice Has Been Done" in the headline, about U.S. Special forces killing Bin Laden, or an article about the Olympics. Participants were asked to say how strongly their current state was described by 25 adjectives, including words such as sad, irritated, mad, angry and happy.

Unlike in earlier work, however, the team used a linguistic analysis to distinguish between self-reported moods and emotions. Moods may last longer than individual emotions, but while moods generally thrum at low levels in the background, emotions are strongly felt.

Reading about Bin Laden's killing put people in a worse mood, but still inspired positive emotions in them, the researchers reported April 28 in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. The team also showed participants versions of the text that were scrubbed of certain charged language, to ensure that their experience of vengeance, rather than the text, inspired their moods and emotions. For instance, participants were shown the article about Bin Laden without including text that portrayed it as retribution. The scrubbed versions still inspired the same general moods and emotions in readers, the scientists found.

"We believe the reason people might feel good about revenge is because it allows us the opportunity to right a wrong and carry out the goal of punishing a bad guy," Eadeh said. "In our study, we found that Americans often expressed a great deal of satisfaction from Bin Laden's death, presumably because we had ended the life of a person that was the mastermind behind a terror organization."

On the other hand, revenge may also inspire negative mood, because exacting revenge may remind victims of the original wrongdoing, which wounds the individuals again, the researchers speculated.

Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.