Evidence of Cannibalism: Did Neanderthals Eat Each Other?

Neanderthal bones uncovered in a Belgium cave show unmistakable signs of butchery, and scientists said they are the first evidence of Neanderthal cannibalism in northern Europe.

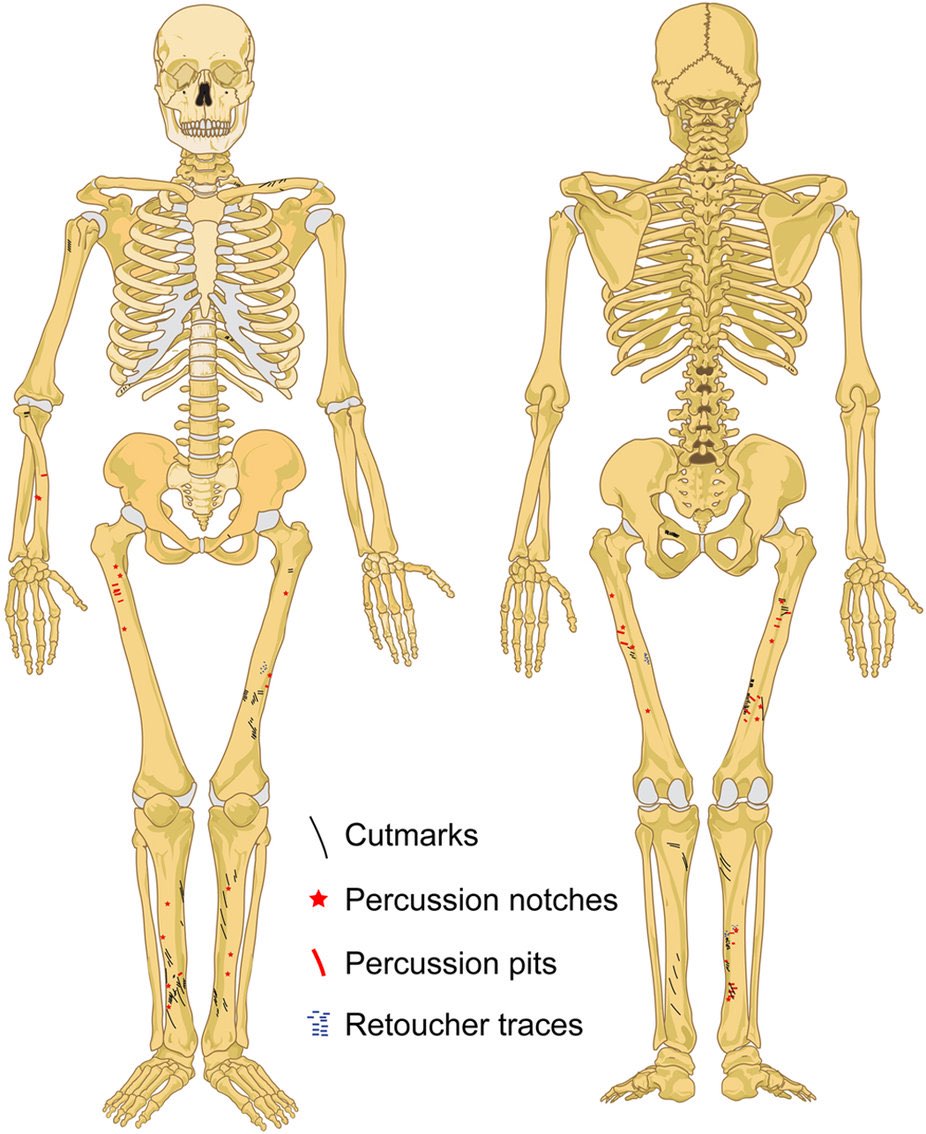

Archaeologists pieced together 99 bone fragments to identify five distinct Neanderthals, four adults and a child, who lived between 40,500 and 45,500 years ago. Markings on the bones included indentations from hammering (likely to remove bone marrow), and cut marks from carving the flesh away from the bone. Also in the cave were the remains of horses and reindeer, which had been similarly butchered.

"Similarities in anthropogenic [human-created] marks observed on the Neanderthal, horse and reindeer bones … suggest similar processing and consumption patterns for all three species," the scientists wrote in their research, published this week (July 6) in the journal Scientific Reports. [Image Gallery: Our Closest Human Ancestor]

The Neanderthal remains provide "unambiguous evidence" of cannibalism, the researchers said. Other Neanderthal bones have also shown signs of cannibalism, but the Belgian site is the farthest north to do so — showing regional variability of Neanderthal mortuary behavior. The other discoveries were in France, Portugal and Spain, where scientists found a group of Neanderthals, including an infant, who may have been cannibalized by another group of Neanderthals.

Beyond cannibalism, it appears that the Neanderthals also used their peers' remains as tools. A few of the bones bore markings that suggested they'd been used to help sharpen stone tools.

This new research adds to the overall understanding of Neanderthals' relationship with the dead, as their behavior toward the deceased varied from preparing burials to using the bodies for food or creating tools, the researchers noted.

"The big differences in the behavior of these people on the one hand, and the close genetic relationship between late European Neanderthals on the other, raise many questions about the social lives and exchange between various groups," Hervé Bocherens, one of the lead researchers, told CBS News.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

An analysis of DNA within the Neanderthal mitochondria (energy-making organelles in cells that carry their own DNA) suggested that the Belgian Neanderthals were genetically similar to other Neanderthal communities living in Germany, Spain and Croatia. This suggests the Neanderthal population in Europe at the time was small, as there was "only modest genetic variation despite large geographic distances when compared to modern humans," the scientists wrote.

The Neanderthals went extinct about 30,000 years ago, and are modern humans' closest extinct relatives.

Original article on Live Science.