The Turing test, the quintessential evaluation designed to determine if something is a computer or a human, may have a fatal flaw, new research suggests.

The test currently can't determine if a person is talking to another human being or a robot if the person being interrogated simply chooses to stay silent, new research shows.

While it's not news that the Turing test has flaws, the new study highlights just how limited the test is for answering deeper questions about artificial intelligence, said study co-author Kevin Warwick, a computer scientist at Coventry University in England. [Super-Intelligent Machines: 7 Robotic Futures]

"As machines are getting more and more intelligent, whether they're actually thinking and whether we need to give them responsibilities are starting to become very serious questions," Warwick told Live Science. "Obviously, the Turing test is not the one which can tease them out."

Imitation game

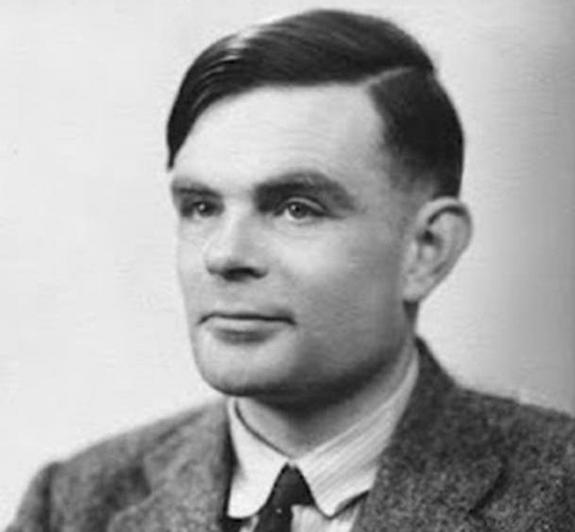

The now-famous Turing test was first described by British computer scientist Alan Turing in 1950 to address questions of when and how to determine if machines are sentient. The question of whether machines can think, he argued, is the wrong one: If they can pass off as human in what he termed the imitation game, that is good enough.

The test is simple: Put a machine in one room, a human interrogator in another, and have them talk to each other through a text-based conversation. If the interrogator can identify the machine as nonhuman, the device fails; otherwise, it passes.

The simple and intuitive test has become hugely influential in the philosophy of artificial intelligence. But from the beginning, researchers found flaws in the test. For one, the game focuses on deception and is overly focused on conversation as the metric of intelligence.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For instance, in the 1970s, an early language-processing program called ELIZA gave Turing test judges a run for their money by imitating a psychiatrist's trick of reflecting questions back to the questioner. And in 2014, researchers fooled a human interrogator using a "chatbot" named Eugene Goostman that was designed to pose as a 13-year-old Ukrainian boy.

Right to remain silent

Warwick was organizing Turing tests for the 60th anniversary of Turing's death when he and his colleague Huma Shah, also a computer scientist at Coventry University, noticed something curious: Occasionally, some of the AI chatbots broke and remained silent, confusing the interrogators.

"When they did so, the judge, on every occasion, was not able to say it was a machine," Warwick told Live Science. [The 6 Strangest Robots Ever Created]

By the rules of the test, if the judge can't definitively identify the machine, then the machine passes the test. By this measure then, a silent bot or even a rock could pass the Turing test, Warwick said.

On the flip side, many humans get unfairly tarred as AI, Warwick said.

"Very often, humans do get classified as being a machine, because some humans say silly things," Warwick said. In that scenario, if the machine competitor simply stayed silent, it would win by default, he added.

Better tests

The findings point to the need for an alternative to the Turing test, said Hector Levesque, an emeritus computer science professor at the University of Toronto in Canada, who was not involved with the new research.

"Most people recognize that, really, it's a test to see if you can fool an interrogator," Levesque told Live Science. "It's not too surprising that there are different ways of fooling interrogators that don't have much to do with AI or intelligence."

Levesque has developed an alternative test, which he dubbed the Winograd schema (named after computer science researcher Terry Winograd, who first came up with some of the questions involved in the test).

The Winograd schema asks AI a series of questions that have clearly correct answers. For example, it might ask, "The trophy would not fit in the brown suitcase because it was too big (small). What was too big (small)?"

These queries are a far cry from the rich discussions of Shakespearean sonnets that Turing envisioned taking place between AI and humans.

"They're mundane and certainly nowhere near as flashy as having a real conversation with somebody," Levesque said.

Yet, answering correctly requires an understanding of language, spatial reasoning, and context to figure out that trophies fit in suitcases.

And still other proposed alternatives to the Turing Test have focused on different aspects of human intelligence, such as creativity.

The Lovelace test to measure creativity requires a robot to create a piece of artistic work in a particular genre that meets the constraints given by a human judge. But even in this domain, robots are gaining on mere mortals: Earlier this year, researchers created a "new Rembrandt" painting in the style of the Dutch master, using artificial intelligence and robot painters.

Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.