Beyond Balloons: 8 Unusual Facts about Helium

Up, up and away

The things most people know about helium are that it makes balloons float up and it makes your voice squeaky if you inhale some. But helium is more than just fun and games: it is also a scarce industrial resource with important uses in technology and medicine — and scientists are still learning more about its many strange properties.

So let's get this party started, with some of the most unusual applications and facts about helium.

Lighter than air

Helium is one of lightest and least dense of all the chemical elements, thanks to the chemical stability and extremely small size of single helium atoms. Helium's low density is what causes balloons filled with the gas to float, buoyed up by the denser surrounding air.

Under the sea

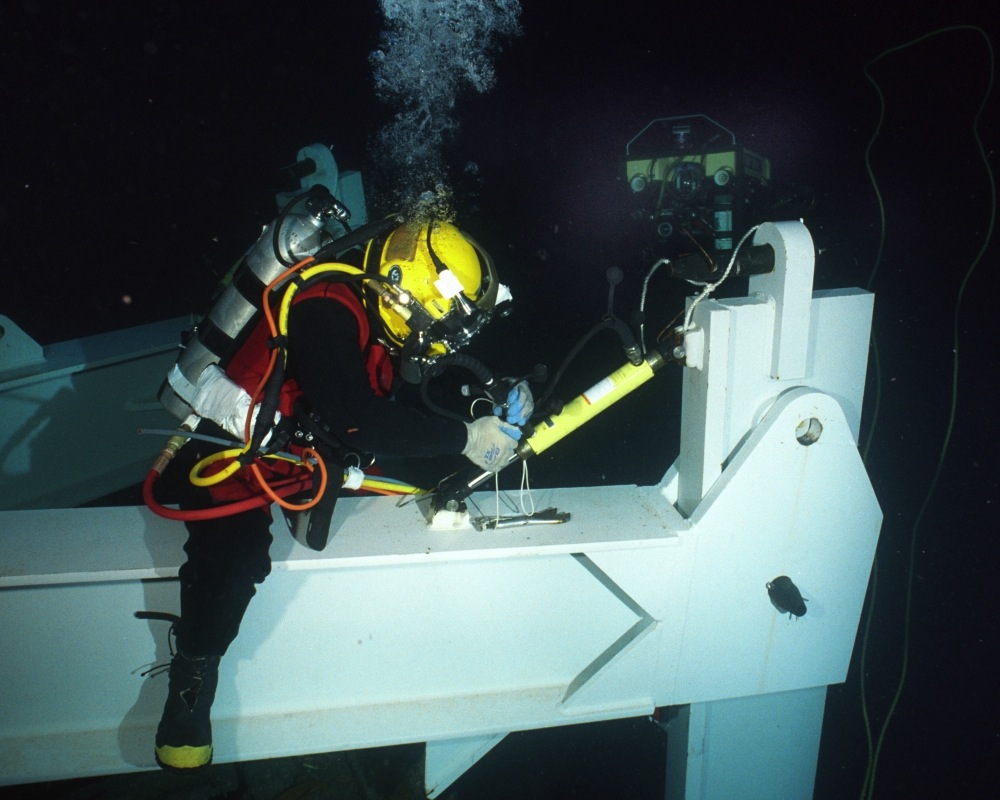

Because helium is easily compressed and non-toxic, it is used in specialized "breathing mixtures" of gases for very deep scuba diving, as a replacement for the nitrogen that makes up about 75 percent of our air.

At high pressures, such as underwater below around 100 feet (30 meters), dissolved nitrogen can quickly build up in body tissues and cause fatal decompression illness, or dangerous bouts of "nitrogen narcosis," an effect similar to sudden and extreme drunkenness.

To get around the problems of breathing nitrogen, technical and commercial divers who plunge to depths of up to 400 feet (122 m) or beyond use breathing mixtures like "heliox," in which the fraction of nitrogen in the air has been replaced with helium.

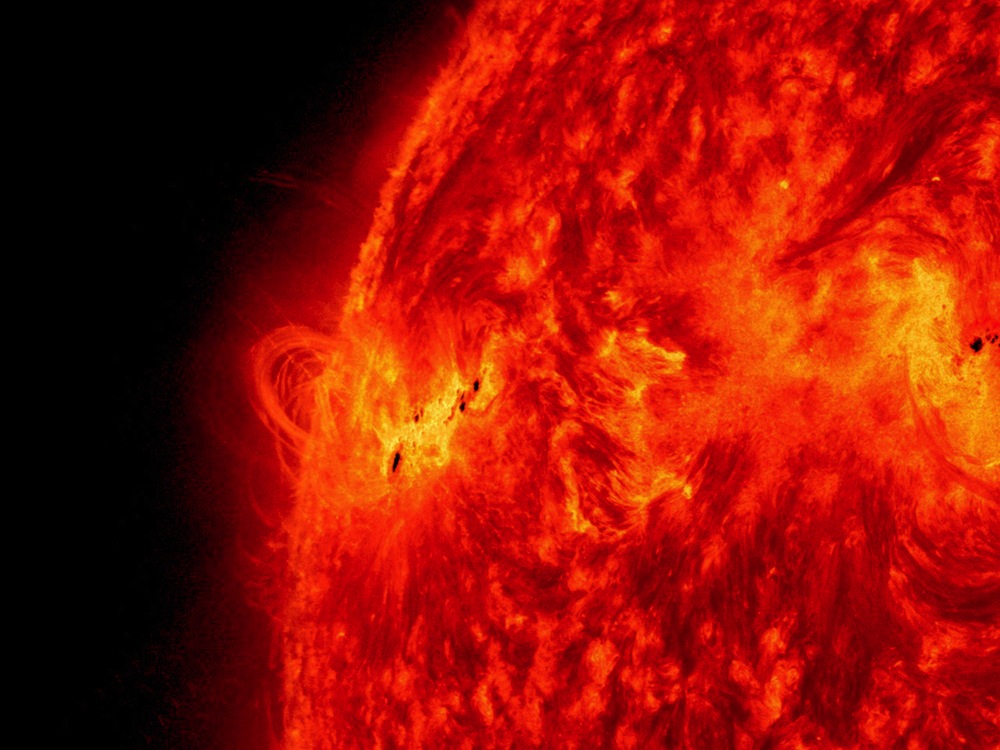

Powering the sun

Helium takes its name from "Helios," the Greek god of the sun, which was where the chemical element was discovered in the 1860s, by astronomers studying the signature "gas absorption lines" of the color spectrum of sunlight.

Helium makes up around 45 percent of the mass of the sun, where it is formed at scorching temperatures by the fusion of hydrogen — the primary process that keeps the sun and all the stars burning.

In turn, atoms of helium are fused in stars to create the heavier elements, including carbon, oxygen and silicon.

Over the moon

Most helium atoms have two proton and two neutron particles in the nucleus, an isotope called helium-4. But some form an isotope with two protons and just one neutron, called helium-3, which has been proposed as an ideal fuel for fusion power generation.

Helium-3 is almost unknown on Earth. But, it has been identified in large quantities on the moon, where helium from the solar wind has rained onto the lunar surface for billions of years. Several space agencies, including those in Russia, China and India, have suggested helium-3 could provide a potential payoff for lunar exploration.

Super cool

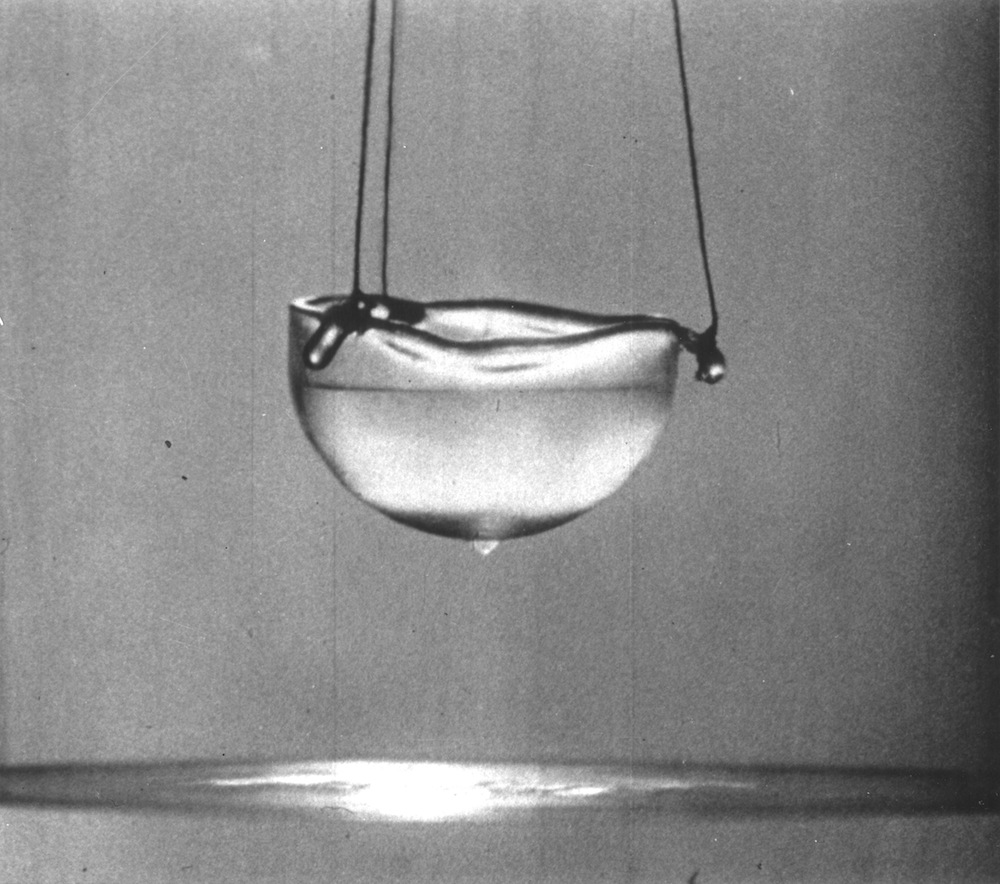

Helium gas condenses into a liquid at extremely low temperatures, around minus 450 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 268 degrees Celsius) at atmospheric pressure, and starts to exhibit very strange behavior at even lower temperatures.

Below minus 456 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 271 degrees C), just a shiver above absolute zero, helium-4 becomes a so-called superfluid, with about 1/8th of the density of water and zero friction. Among the many curious properties of superfluid helium is its ability to quickly flow through any leak, and even upwards along the walls of a container, which means it's extremely difficult to keep it from escaping.

Inner vision

Because helium easily liquefies at such low temperatures, it is used as a coolant for powerful superconducting electromagnets, such as the magnets used in the Large Hadron Collider near Geneva, Switzerland.

Liquid helium is also used to cool the ring-shaped magnetic coils in hospital MRI scanners to temperatures of about minus 441 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 263 degrees C), which allows them to generate brief but intense magnetic fields.

The magnetic fields cause atoms inside the body to resonate with their own magnetic signatures, which can be detected by the scanner and used to build a detailed image of internal organs and tissues.

In short supply

It takes billions of years for pockets of helium to form in the Earth’s crust from the radioactive decay of uranium and thorium. This makes it hard to find, and for many years, the price of helium for applications like MRI scanners has been rising.

For many years, the world’s single main supplier was the Federal Helium Reserve near Amarillo, Texas, which was established after World War I to secure American supplies of helium as a lifting gas for military airships.

In the 1950s, during the Cold War, helium found a new use: purging and pressurizing the rocket engines of nuclear missiles and space missions.

Helium horde

In recent years, some natural gas producers in the U.S., Canada and Qatar have started to tap small concentrations of helium, which has eased the rise in price.

Recently, scientist announced the discovery of a major helium gas field at Rukwa, in the East African Rift Valley region of Tanzania, which may be even larger than the entire helium reserves of the United States.

This discovery and others like it may ease global demand, but scientists have warned that helium is the “ultimate non-renewable resource” – hard to find, difficult to keep, and impossible to recycle.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.