How'd They Do That? The Best Illusions of 2016 Named

Tricks of the mind

When things aren't what they seem, it can be unnerving, but under the right circumstances these kinds of illusions can be utterly captivating. On July 1, the finalists and winner of the 2016 Best Illusion of the Year Contest were announced by the Neural Correlate Society.

From illusions that play tricks with motion to ones that use shadows to fool your mind, this year's finalists make up a perplexing collection.

To help you make sense of what you're seeing, Allison Sekuler, director of the Vision and Cognitive Neuroscience Lab at McMaster University and a judge of this year's contest, explained to Live Science some of the general principles behind a few of the finalist illusions.

"Illusions will often tell us something about how the brain works," Sekuler said, but "in many of the cases, we don't actually understand all of the elements underlying the illusion."

In some instances, the novelty and possible scientific value come from combining aspects of existing illusions. "Different elements may not be original, but it's the way they put things together that's completely new," Sekuler said.

Integrated motion

In this year's winning illusion, a series of banded blobs appear to form a rotating square. The patches are stationary, so it's only the movement of the stripes at various speeds that creates the illusion of a larger shape moving. "The brain is trying to reconcile the fact that there is local motion, but a shape that is grouping itself together," Sekuler said. "The brain is trying to solve puzzles. How can I come up with something that puts it all together that could be physically possible?"

The illusion uses a stimulus, the so-called curveball illusion that was named the 2009 illusion of the year.

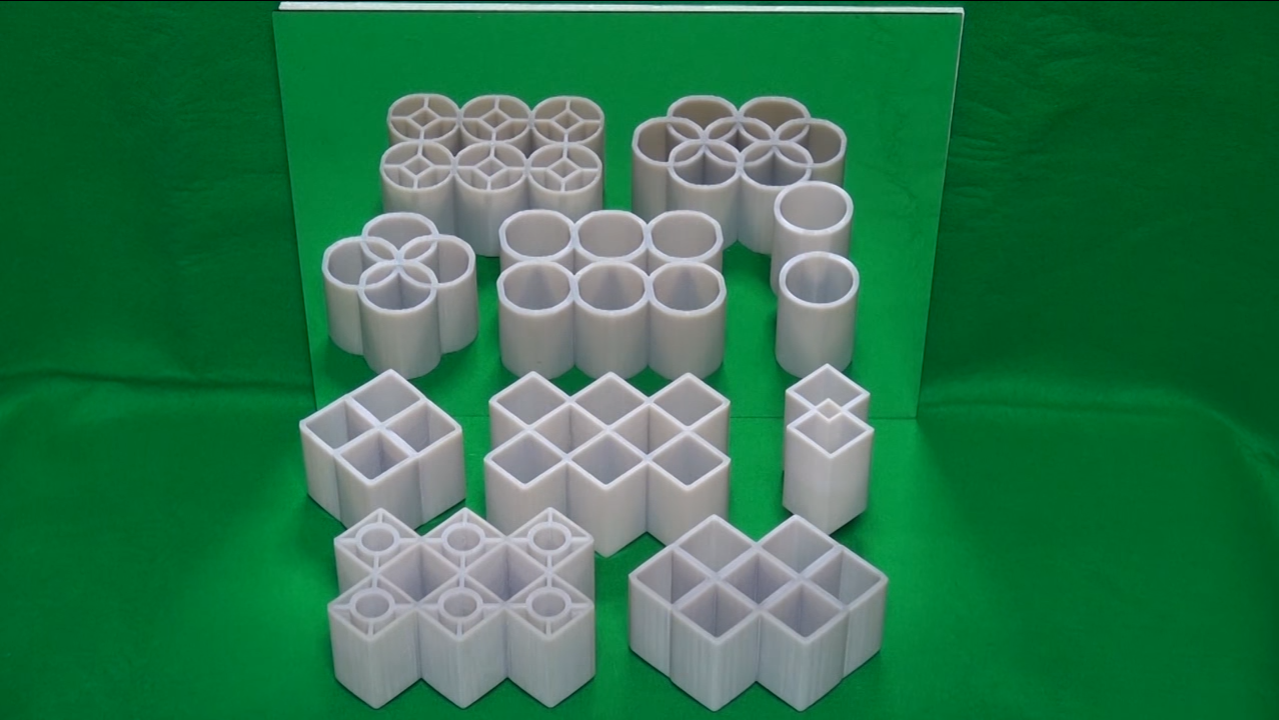

The ambiguous cylinder

As the name suggests, these remarkable 3D-printed objects seem to change shape depending on their orientation. "People see it as a circle or as kind of a diamond — in reality, that structure is neither of those things," Sekuler said. "It's a shape that was created so that from a particular perspective you'll see it as one thing or another."

And because the two shapes are so different, it's difficult for people's brains to combine them, she added.

"It makes more sense to say there are two different objects," Sekuler said. "It sounds almost counterintuitive … in this case, the simplicity that's winning out is our familiarity with those shapes."

The researcher, Kokichi Sugihara of Meiji University in Japan, used ambiguous shapes and perspective to craft an illusion that was named a 2015 finalist and one that was a 2010 winner.

Flight in silhouette

One principle at play in all zoetropes is apparent motion, in which a series of similar images presented in quick succession appear to be one object in motion, "which is exactly what happens in animation," Sekuler said.

As the viewer consolidates the many spinning birds into a single image, they have to go somewhere. "The place that makes sense in the case of the zoetrope is right in the middle of where all those objects are," Sekuler said.

And the bird in flight appears to reverse directions, which may have something to do with the ambiguity of animations in silhouette. "When it's just a silhouette, you can misinterpret the direction of motion," Sekuler said.

Technicolor Bubbles

There are probably multiple misperceptions happening at once in this illusion, similar to the 2008 Illusion of the Year. As the screen alternates between colorful concentric circles and colorless circles of different sizes, the viewer perceives an opposite color filling in the blanks.

The illusion involves afterimages, a reversed color shape that lingers on a neutral background after you've just viewed an image. They're a product of the way we process color vision, "with different groups of neurons working in opposition to each other," Sekuler said.

Sekuler compares the illusory colored circles to the watercolor illusion, in which a thin band of color on the inside of a well-defined contour can give the illusion of a colorful interior. Except in this case, "it's not really a color; it's an afterimage color," she said. "Usually when you have an afterimage, you would see an afterimage of the whole object," but in this case, the outlines define perception of the colored area, Sekuler added.

An elbow illusion

Sekuler remembers this tactile illusion, in which people with eyes closed anticipate a touch reaching their elbow, from her childhood. There are a variety of touch-based illusions that rely on the brain working with limited information from less sensitive body parts.

"There's different sensitivity levels on different parts of your skin," Sekuler said. "It's harder to convey how cool they are over the internet because it's such a visual medium," she said, adding that she recommends trying this illusion with a friend.

Sekuler said persons being touched should keep their arm straight and not touch the crook of their elbow beforehand, or it will give them a sense of what to expect.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.