The Psychology of 'Pokémon Go': What's Fueling the Obsession?

Perhaps you've seen them: roving bands of (mostly) young people, gathering together with smartphones aloft, talking about something called Rattata or Squirtle.

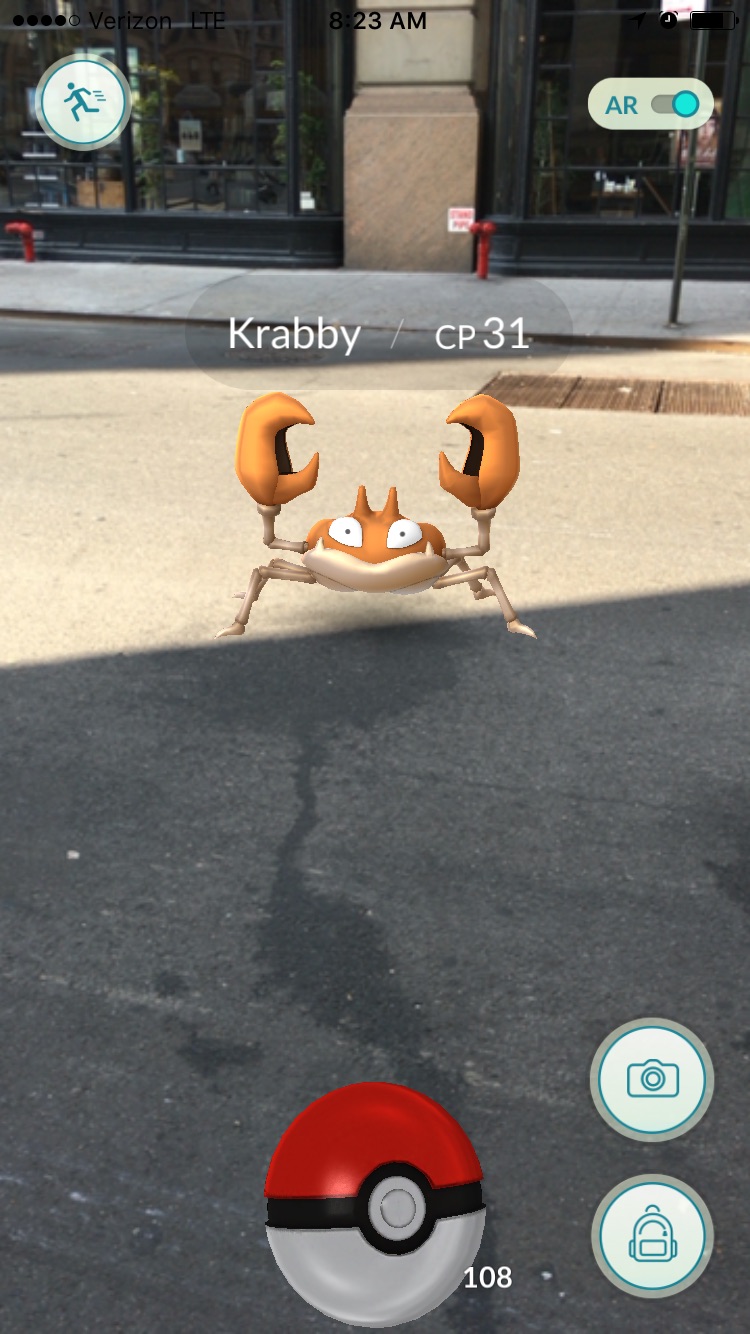

If not, you've probably at least seen the headlines about these folks — players of the massively popular new game "Pokémon Go." The game, which uses geolocation to place virtual Pokémon characters in the real world, has breathed sudden new life into the 20-year-old Pokémon franchise, with some estimates suggesting that the game has been downloaded more than 7 million times in the U.S. since its release on July 6.

Part of its success owes to its deft mixing of the real world and the virtual world. "Pokémon Go" blends a game experience with real physical activity and real, in-person socialization, said Pamela Rutledge, director of the Media Psychology Research Center in Newport Beach, California. [Check out this Pokémon Go Guide from our sister site Tom's Guide.]

Ultimately, the features that come together in Pokémon Go appeal to real human desires, such as a need for social connection. "It's really ticking the boxes of the major drivers of human behavior," Rutledge said.

Catch 'em all

Though virtual reality has been getting a lot of buzz lately as companies like Facebook try to get into the gaming market, augmented reality (including "Pokémon Go"), which brings virtual enhancements to your own environment, has some major advantages over gaming from inside a headset, Rutledge told Live Science.

"With virtual reality, the tech hasn't been developed enough so that people can uniformly use it and not feel motion sickness," she said.

That problem doesn't exist with "Pokémon Go," which doesn't aim for hyper-realistic panoramic views as virtual reality experiences do. Instead, the game is played on tiny smartphone and tablet screens. The screens have to be portable, because the game requires players to be at certain spots to "catch" Pokémon and to battle them against one another. The algorithms are sophisticated enough to put Pokémon in areas suited to the real-world environment — water-dwelling characters near the beach, for example, and nocturnal characters for players out at dusk.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Other games have tried to capitalize on augmented reality. One is Ingress, a game with a complicated backstory that requires players to physically go to geolocated "portals" in order to win them from the opposing team. But no game has made the splash that "Pokémon Go" has.

The pre-existing social awareness of Pokémon has probably helped the game's rapid adoption, Rutledge said. Even people who don't play the game have heard of or seen the cartoonish creatures that players try to capture.

Augmenting reality

The game itself scratches some basic psychological itches, Rutledge said: the need to socialize with other people; the desire to go out and act on the world in a measurable way; and the need for competence and mastery, which is met by the game's goal to "catch 'em all!"

There are dangers to moving around the real world with one's nose stuck in a phone, but the game does urge players to pay attention to their surroundings, Rutledge noted. In many ways, the game could be psychologically beneficial, she said. Players are up and moving around, and "zillions" of studies have found a mood-boosting effect of physical activity, she said. Social ties are important for mental health, too, and some research suggests that even shallow conversation with strangers boosts well-being.

"One of the features of this game is allowing you to actually challenge one of the major complaints about gaming": that it's sedentary and isolating, Rutledge said.

Augmented reality, including "Pokémon Go," she said, "allows you to bring fantasy into your own life but within your own control."

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.