Images: Human Parasites Under the Microscope

Under the Microscope

Parasites. They can invade the blood, the digestive tract, even the bile duct. They enter through the mouth, through the skin, through the nose. They can cause disease, blindness and sometimes death.

Full body shudders, right? But as disgusting as parasites are, they're also elegant examples of evolution. The following images reveal these dangerous organisms in microscopic detail.

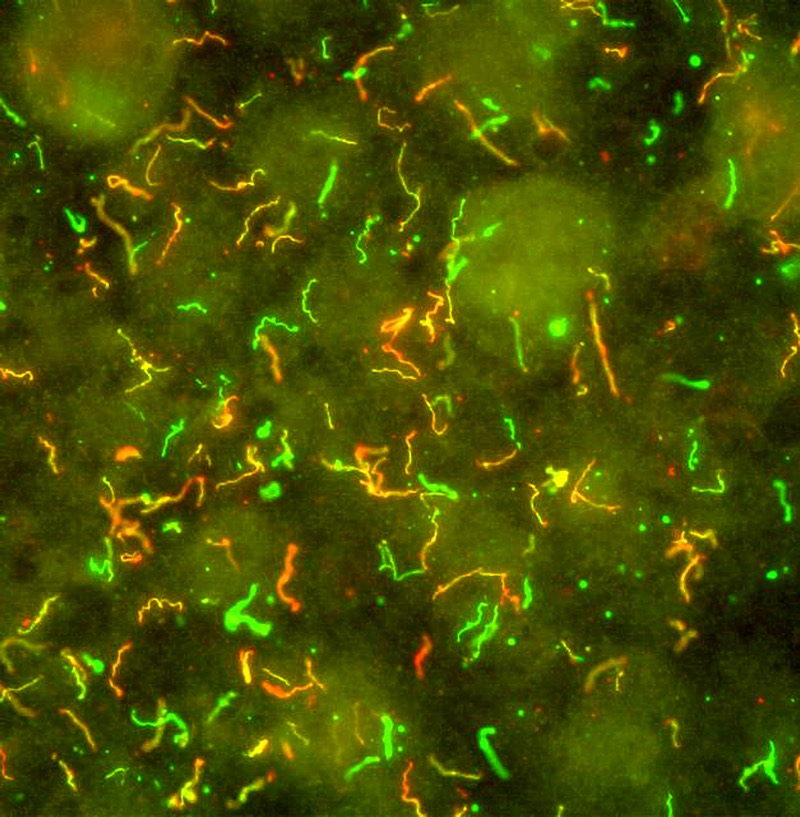

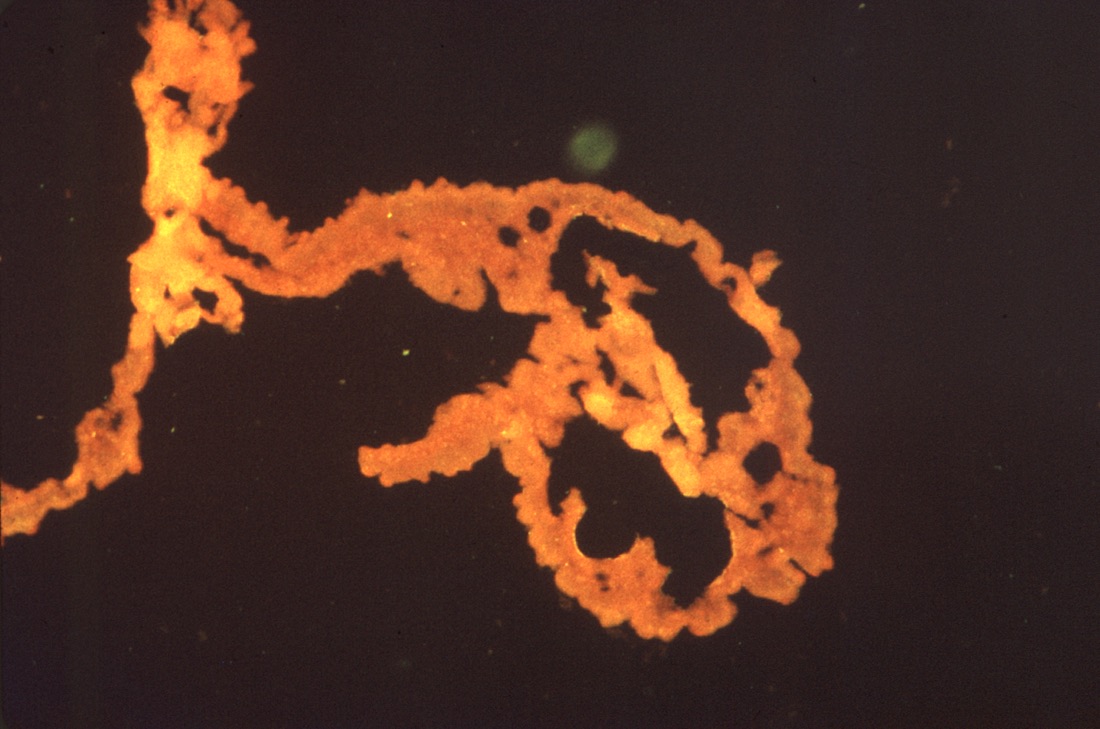

A tick-borne bacteria

This confetti-like image is Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria that causes Lyme Disease. This parasite evolved to live in the blood of small mammals, which usually don't show any ill effects of infection, according to a 2009 paper published in the journal Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. But when ticks of the Ixodes genus feed on small mammals, they can go on to transmit the parasite to larger vertebrates — including humans. Once infected, people experience fatigue, fever and often a red, circular rash that may look like a bull's-eye. Without treatment (with antibiotics), Lyme disease can progress and cause arthritis, meningitis and neurological symptoms like pain and numbness.

The dreaded tapeworm

No microscope is needed for a close look at the tapeworm Taenia saginata, which regularly reaches 33 feet (10 meters) in length. This tapeworm hatches inside the digestive tract of cattle, and larvae spread into the muscle. The worm spreads to humans who eat raw or undercooked beef from an infected cow. Once in the human host, the worm attaches to the intestinal wall, siphoning nutrients and self-fertilizing to make eggs excreted through the feces — hopefully, from the worm's point of view, into a field where a cow might be grazing.

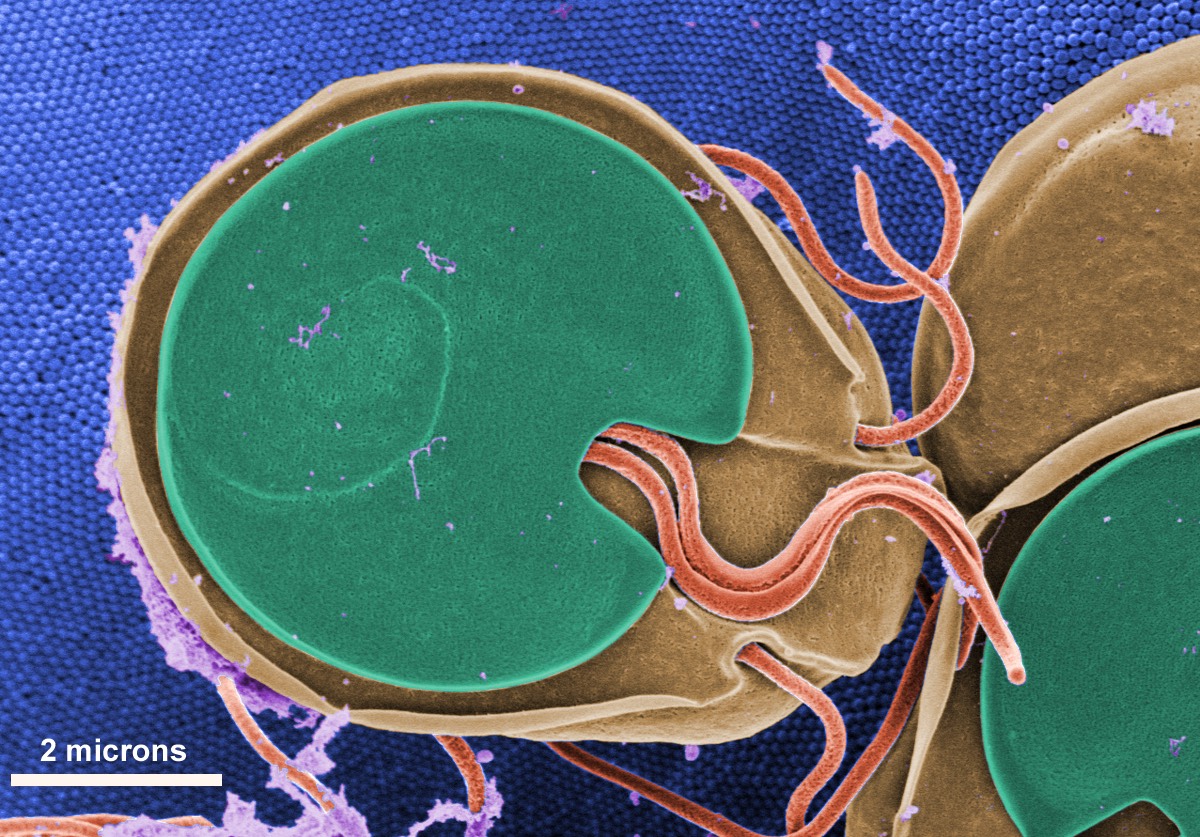

Diarrheal disease

Giardia, a parasitic protozoan transmitted by untreated drinking water, causes giardiasis, a diarrheal illness accompanied by nausea and fatigue. Under a microscope, the protozoan's adaptations for life in the digestive system are visible: A suction-cup disk for adhering to surfaces and four pairs of flagella for moving around.

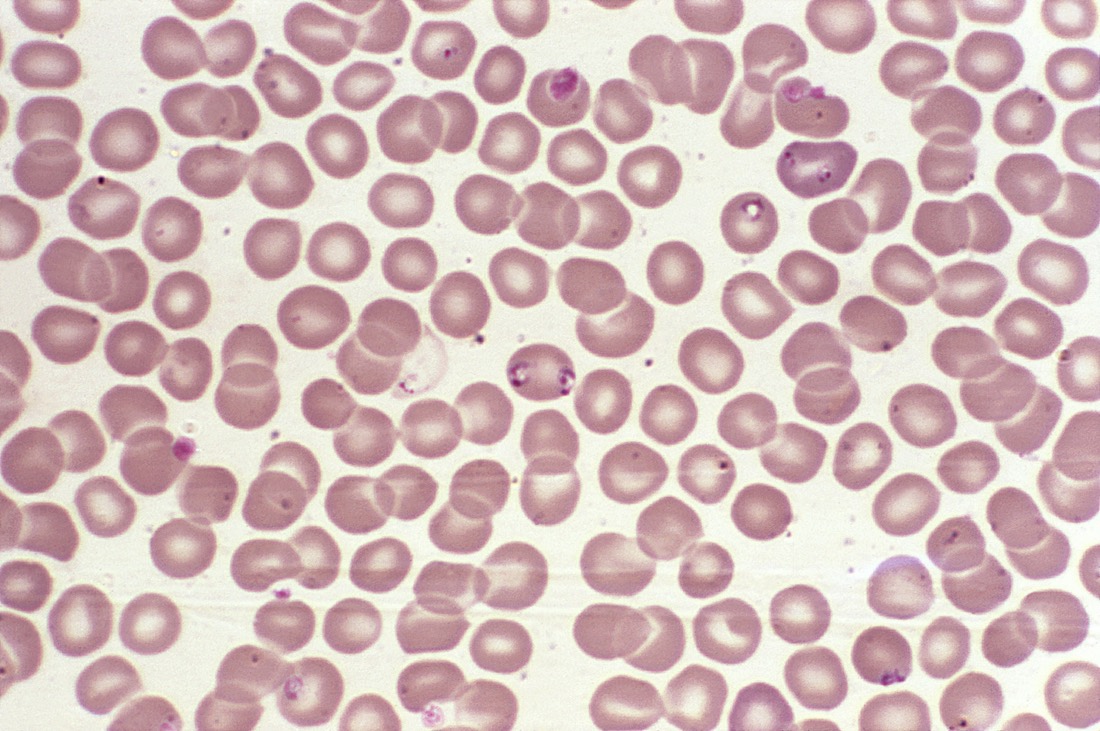

Invading the blood

The dark pink specks in this microscopic image of blood are hemoprotozoan parasites called Babesia. This is a tick-borne illness seen in the Midwest and the Northeast. The symptoms are a bit like those of malaria: Fever, anemia, fatigue and chills. Ixodes scapularis ticks – the same kind that spread Lyme disease — are also responsible for passing around Babesia parasites. The protozoa reproduce inside red blood cells, often budding to form a trademark four-pronged cross shape.

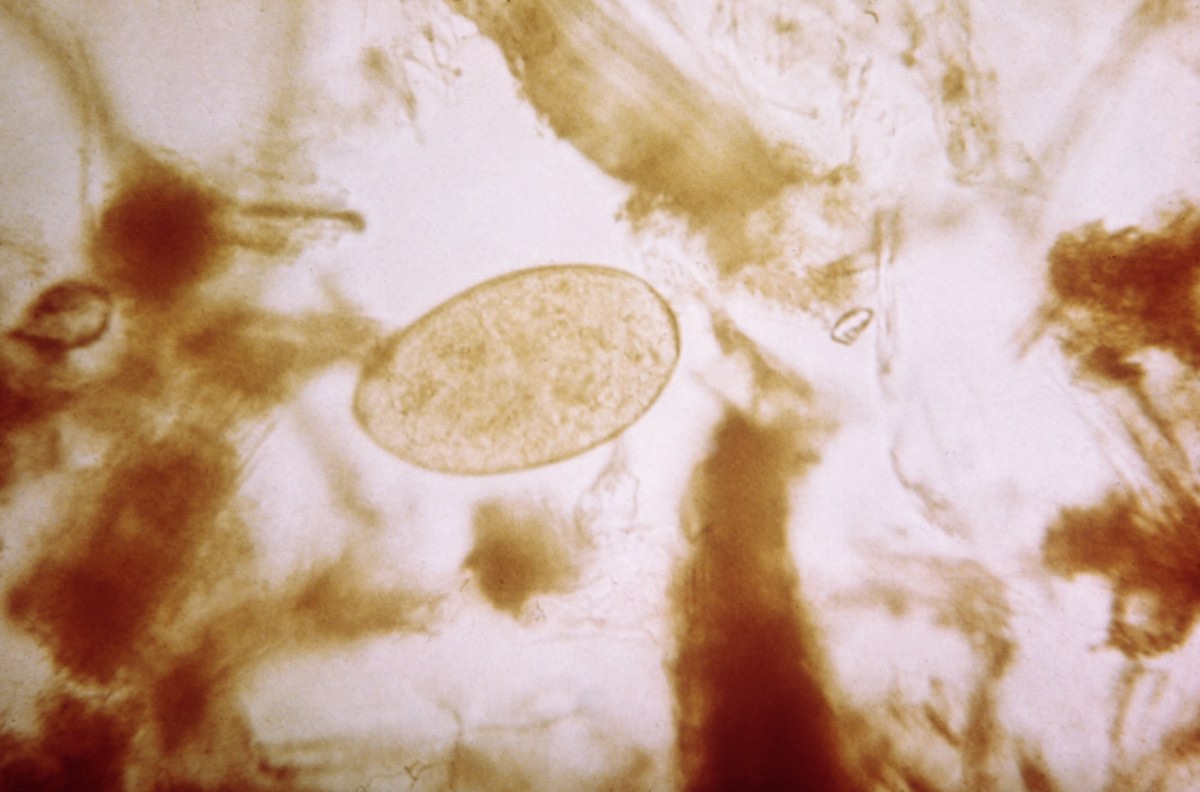

Sheep liver fluke

This unassuming oval is the egg of Fasciola hepatica, the sheep liver fluke. Despite its name, this fluke can infect humans, where it sets up shop in the liver and bile ducts. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, people usually pick up an infection by eating watercress or other aquatic plants. The parasite can cause chronic inflammation of the liver, bile ducts, gallbladder and pancreas, according to the CDC.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Spread through snails

Schistosoma mansoni, is a parasitic worm spread when human skin comes into contact with infested water. This worm lives its life cycle in two hosts: Freshwater snails (where the eggs hatch into free-swimming larvae) and vertebrates, including humans. The ensuring disease is called schistosomiasis or, sometimes, swimmer's rash after the itchy red rash people often experience after the larvae penetrates their skin. Chronic infection can lead to damage in the intestine and bladder as the worms release their eggs, according to the CDC.

Hello, hookworms

Hookworms: A good reason not to go barefoot in the summer, at least not when walking through a freshly fertilized field. These nematodes spread when an infected person defecates outside; the worm eggs hatch in the soil and then develop into larvae capable of burrowing into bare skin. According to the CDC, hookworm used to be widespread in the United States, but improved hygiene has greatly reduced infections.

Many people carry hookworms in their intestines without symptoms, but the parasites can cause gastrointestinal distress and sometimes anemia.

Guinea worms

Among the most spine-tingling parasites is the Guinea worm, a nematode that doesn't have the decency to even stay inside its host. Guinea worms spread when humans ingest untreated water. They hatch in the digestive system and migrate and reproduce inside the body. The female then journeys to the muscle and skin and makes her escape, trying to emerge through a blister over excruciating weeks.

To extract the worm more swiftly, doctors often try to wrap it around a stick, slowly winding it out of the wound over several days. Because female guinea worms can grow up to 31 inches in length (80 centimeters), this is a slow, disgusting and painful process.

Botfly larva

Here's something you don't want to see squirming under your skin. This is the larva of the Cuterebra botfly, a parasitic fly. This particular larva infects rodents and rabbits, but a closely related parasite, Dermatobia hominis, targets humans.

Adult female flies spread their eggs to humans in a surprising way: They snag a mosquito or tick and lay their eggs on the unsuspecting vector's body. When the insect goes on to bite a person, the eggs or hatched larvae drop off and enter the skin, where they develop for a couple of months before emerging to complete their life cycle as free-living organisms. During the larval stage, the maggots are often visible as small bumps and must be surgically removed from the skin.

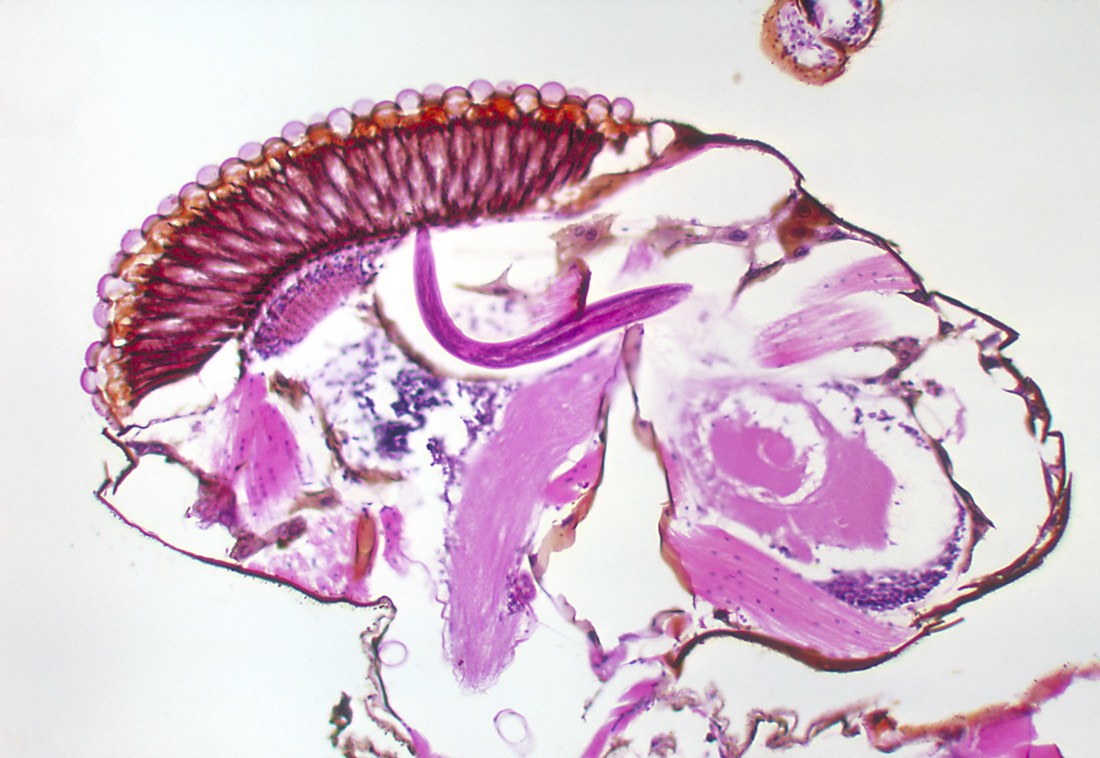

River blindness

The pink, wormy swoosh visible in the center of this image is Onchocerca volvulus, a nematode seen developing in a black fly. Black flies are blood-feeders that spread O. volvulus with their bites. In the human body, the worms roost in subcutaneous tissues, mating and reproducing. When the worms migrate to the eye tissue, they can cause the cornea to go opaque, a condition called onchocerciasis, or river blindness.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents