10 Amazing Women Who Turned the Tide of History

Troublemakers and groundbreakers

Throughout history, women around the world have confronted seemingly insurmountable obstacles when pursuing education, career opportunities and accolades typically reserved for men.

But time and time again, ambitious, exceptional women from all cultures proved that they were more than capable of achieving groundbreaking accomplishments, even when unsupported or even vehemently opposed by society's established leaders.

Here are 10 extraordinary women — activists, scientists and innovators — whose remarkable deeds merit attention, recognition and acclaim.

Sybil Ludington (1761-1839)

Like the more celebrated Paul Revere, Sybil Ludington also completed a grueling nighttime ride to alert colonial militia to a British attack — and she did it when she was only 16 years old.

When British troops descended on the town of Danbury, Connecticut, on April 26, 1777, a teenage Ludington, whose family lived nearby, set out on horseback to alert scattered fighters and to urge them to gather at the Ludington house under her father's command.

Her ride began after 9 p.m. and lasted through daybreak, covering approximately 40 miles (64 kilometers), according to Historic Patterson. While the revolutionary forces failed to repel the British from Danbury that day, Ludington's courage earned her the recognition and thanks of George Washington, which he delivered in person at her family home, an event described by the National Women's History Museum.

Elizabeth Jennings (1830-1901)

Known as "the schoolteacher on the streetcar," Elizabeth Jennings stood up for her civil rights by sitting down. Much like Rosa Parks — but more than a century earlier — Jennings challenged segregation when she was 24 years old by insisting on her right to a seat on a New York City streetcar, even after a white conductor ordered her to leave.

During the July 16, 1854, incident, Jennings was forcibly removed from the vehicle and pushed into the street by the conductor and a police officer.

After her letter describing her treatment was published in the New York Tribune, she successfully sued the Third Avenue Railway Company. Jennings was represented by Chester A. Arthur — who would become president of the United States in 1881 — and she collected $225 in damages, according to the African American Registry.

Her case established an important precedent, and most of the streetcar lines in New York City were integrated by 1860.

Ida Wells (1862-1931)

Writer, suffragist and civil rights activist, Ida Wells launched what would become a lifelong public campaign against injustice at the age of 25. In 1884, the Memphis native filed a lawsuit against the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad Company, after a conductor and two other train workers forcibly removed her from a seat that she refused to vacate for a white passenger.

She won the case in local courts, but her victory was overturned by the Supreme Court of Tennessee. After the suit, Wells used the power of her words to denounce injustice, deadly violence and discrimination against black people in the South, PBS wrote. After moving to Chicago, she continued to decry the horrors of lynching, while also marching for women's suffrage and preventing the establishment of segregated schools.

She later served as one of the founding members — of which only two were women — of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. In 1930, Wells became one of the first African American women to seek public office, when she ran as an independent candidate for state senator.

Marie Stopes (1880-1958)

Marie Stopes published her first scientific study on plants in 1903, and she received a doctoral degree in botany in 1904 from the University of Munich. She was a leading expert at the time in the study of ancient plants, lecturing on paleobotany at the University of Manchester from 1904 through 1910, and her 1910 book, "Ancient Plants," popularized fossil plant life for the general public.

Stopes' work took her to Japan and Canada, where she embarked on geological field studies and searched for traces of ancient plants. While conducting coal research for the British government, she created scientific terminology and a classification scheme for coal that remains in use today.

Stopes was also a pioneer of family planning, and co-founded the first birth control clinic in Britain, which opened in 1921. She wrote extensively about contraception, reproductive health and marriage as an equal partnership between the sexes.

Clara Maass (1876-1901)

Beginning in 1898, Clara Maass served as a nurse during the Spanish-American War, tending primarily to soldiers who had become ill after contracting infectious diseases like dengue, malaria, yellow fever and typhoid.

In 1901, she volunteered to participate in a risky endeavor for the Yellow Fever Commission, which had been established by the U.S. Army to investigate how the disease spread. Maass allowed herself to be bitten by mosquitoes that had fed on yellow fever patients, to test whether the disease could be transmitted through bites of infected mosquitoes.

She contracted yellow fever and recovered, volunteering again to be bitten by mosquitoes as the commission continued to gather evidence. Once more, Maass became ill with yellow fever, but this time it proved to be fatal. Her widely publicized death ended the practice of yellow fever experiments using people, but helped scientists to confirm mosquitoes as a yellow fever vector.

Charlotte Edith Anderson Monture (1890-1996)

Born on the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve in Southern Ontario, Canada, Charlotte Edith Anderson Monture was the first native Canadian woman to train and practice as a nurse. Racial prejudice denied her entry to Canadian nursing programs, and she attended and graduated from a nursing school in New Rochelle, New York, later becoming a public school nurse in New York City.

In 1917, Monture volunteered for the U.S. Army Nurse Corps (USANC). She was sent overseas to work in a military hospital in France, and was one of 14 Native American women who served in the USANC during World War I.

After the war, Monture returned to Canada, where she lived on the Six Nations Reserve and worked as a nurse in a local hospital.

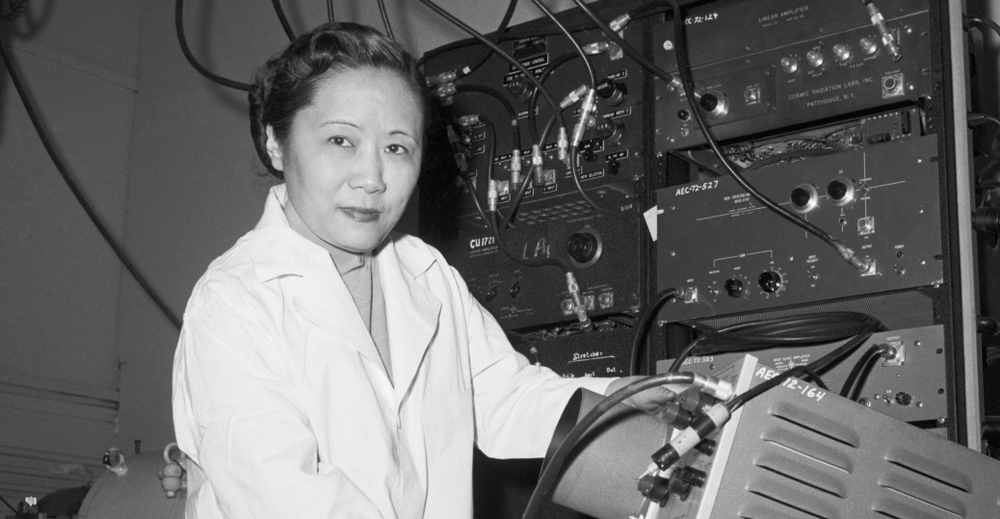

Chien-Shiung Wu (1912-1997)

Known as "The First Lady of Physics," Chien-Shiung Wu studied nuclear fission, leading to her participation in the Manhattan Project — a then-secret collaboration in the 1940s between scientists and the U.S. military to create nuclear weapons.

While working on the Manhattan Project at Columbia University, Wu contributed to the development of a process that separated uranium metal into isotopes through diffusion, increasing the amount of uranium that could serve as fuel for an atomic bomb.

In 1957, Wu and two of her colleagues at Columbia University overturned a law of symmetry in physics, but when their discovery was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics that year, her contributions were overlooked and only her colleagues were recognized.

Despite the snub, Wu continued to garner awards and accolades over the next several decades, becoming the first woman elected to the American Physical Society, the first woman to receive the Cyrus B. Comstock Award of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, and the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate from Princeton University.

Nancy Grace Roman (b. 1925)

"When I was a girl, women were not supposed to be scientists. At least, that's what I was told," astronomer Nancy Grace Roman wrote in an autobiographical essay for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

Roman faced down discouragement and disapproval to pursue a graduate degree and a career in astronomy, and was a vocal advocate for women in the sciences throughout her professional life.

Roman's discovery of irregularities in "normal" stars' orbits and how the quantities of heavy chemical elements in stars change as they age was one of the first clues to reveal to scientists how the Milky Way galaxy evolved.

In 1959 — the first year of NASA's operation — the agency tasked Roman with creating a program that coordinated satellites, sounding rockets, balloons and ground research to support space observation for half a century. Until 1979, she also served in the NASA Office of Space Science as the Chief of the Astronomy and Relativity Programs.

She is also known as the "Mother of Hubble" for her efforts in the development of the Hubble Space Telescope — the first powerful optical telescope in space — which launched in 1990 and remains active to this day.

Wangari Maathai (1940-2011)

The first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize (2004), Wangari Maathai spoke up for democracy and sustainability in her native Kenya. She founded the Green Belt Movement, an environmental initiative whose members plant trees in Africa to prevent soil erosion, provide a source for firewood and store rainwater.

Maathai's organization began as a grassroots campaign in 1977, when she mobilized women to take action by planting trees to counter the deforestation that threatened the livelihood of their rural communities. What began in Kenya soon spread to other countries in Africa, and has led to the planting of more than 51 million trees in Kenya alone, according to the Green Belt Movement website.

Maathai held a graduate degree in biology — the first doctorate awarded to a woman from East and Central Africa. She was also Kenya's first female professor, served as chair of the National Council of Women of Kenya from 1981 to 1987, and she was elected to Kenya's parliament in 2002 by an overwhelming majority — 98 percent of the vote.

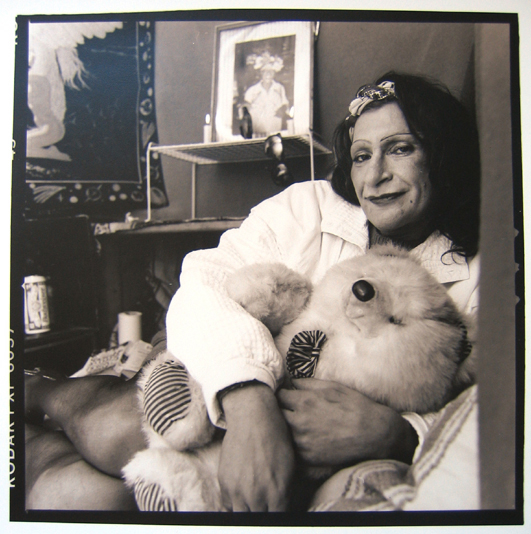

Sylvia Ray Rivera (1951-2002)

Transgender activist and civil rights pioneer Sylvia Rae Rivera was on the front lines of the Stonewall riots in New York City in 1969, which many credit with sparking the modern LGBTQ rights movement.

When police raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar, during the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, Rivera and other Stonewall regulars fought back, triggering a series of protests that extended over several days. By taking a stand against what had been systematic, institutionalized harassment and arrests, Rivera's actions at Stonewall played an important part in mobilizing and uniting the gay community in New York, according to an NBC News profile.

Rivera further participated in the struggle for gay rights with the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), though she later parted ways with the organization when they abandoned agenda items that protected transgender people. She continued to work to promote rights and visibility for gender nonconforming people, especially those in the community who were young or at risk.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.