Eating for exercise shouldn't be complicated: A typical diet will provide all the calories needed to power a workout. In fact, one of the biggest pitfalls for those hoping to get fit is eating to replace the calories burnt during a workout, experts said.

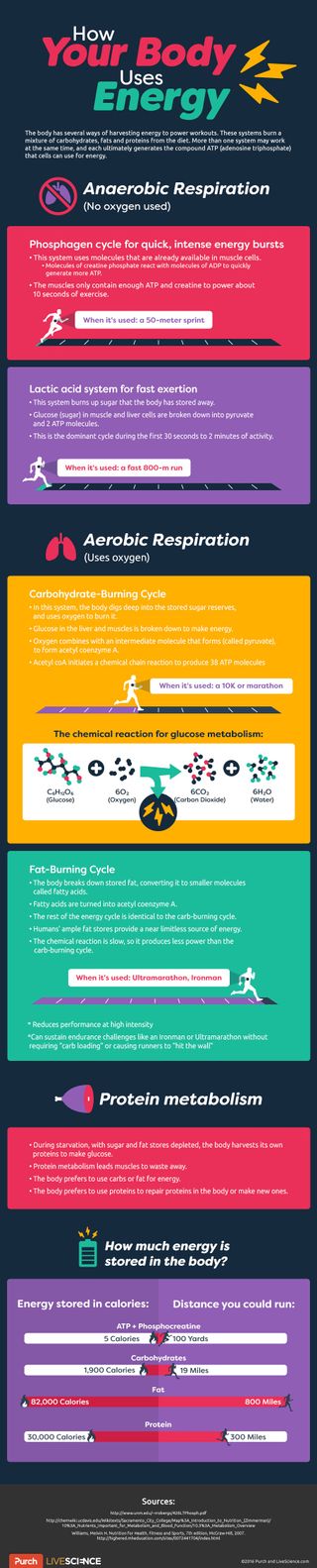

All the calories in food come from these three macronutrients: carbohydrates, protein and fat. The National Institutes of Health recommends that, for most Americans, 45 to 65 percent of daily calories should come from carbohydrates, 25 to 35 percent from fat and 10 to 35 percent from protein. The recommended total calorie intake depends on a person's weight and sex, with a 154-lb. (70 kilograms) person needing to eat about 2,000 calories daily, according to the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Those numbers also hold for the vast majority of people who are exercising, said Dr. Michael Joyner, an exercise physiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

"If people are training at 30 or 40 or 50 minutes a day, they don't need [extra] carbohydrates, they don't need sports drinks, they don't need any of that stuff. People have way overcomplicated this," Joyner said.

Typically, only people who burn more than 500 calories during their workouts need to increase their calorie intake, Joyner said. The vast majority of people who exercise will burn less than this amount. For instance, a 154-lb. person would need to jog for an hour to burn more than 500 calories, and weightlifting burns just 440 calories an hour, according to the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which is published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services.

The body can store at least 1,000 calories' worth of energy in places such as the liver (which stores sugars in the form of glycogen) and the muscles, Joyner added.

For people who exercise moderately, few supplemental calories are unnecessary, agreed Jordan Moon, program director of Sports and Health Sciences and Sports Management at American Public and American Military University and the chief science officer for the body composition and fitness tracking app FitTrace.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In fact, eating to replace calories burned during exercise may backfire, research suggests. For instance, in one study of sedentary women, those who began an aerobic exercise regimen meant to spur weight loss wound up losing just 37 percent of the weight they were predicted to lose based on the number of calories they burned during their workouts. Those findings were published in a 2015 study in the Journal of Strength Conditioning Research. Some of the women actually gained weight. The researchers hypothesized that these exercisers compensated for the energy they burned by eating much more.

A similar study, from 2013 in the journal Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, found that many people who exercise exhibit "compensatory behaviors," such as eating more or moving around less when they're not exercising.

Other research shows that this adaptation may even occur at the metabolic level. For instance, a 2012 study in the journal PLOS ONE found that members of the Hadza hunter-gatherer tribe in Africa were, on average, much more active than the average sedentary Westerner. But nevertheless, the Hazda burned about the same number of calories every day as Westerners did. That finding suggests that the body may tend to adapt to a higher activity level by making the basal metabolism more energy-efficient when people are at rest, the researchers hypothesized.

Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.