10 Historical Treasures That the World Lost in the Past 100 Years

Lost Treasures

From the Ténéré Tree, hit by a driver in 1973; to the priceless artifacts destroyed by ISIS; to a bulldozed Mayan pyramid, here are 10 treasures the world has recently lost.

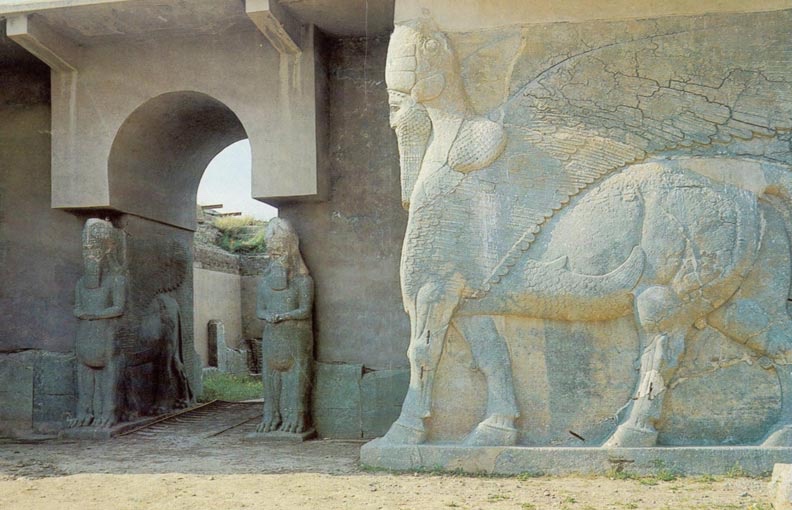

Nimrud

An ancient city in Iraq, Nimrud became the capital of the Assyrian Empire during the reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (reign 883 B.C. to 859 B.C.). The Assyrian Empire stretched from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea; Ashurnasirpal II's palace was adorned with ivory and stone reliefs, which showed the king hunting, fighting and taking part in religious rituals.

In 2015, the terrorist group ISIS destroyed the city using a combination of explosives and bulldozers. Only a small part of the city— mainly the area containing palaces — had been excavated by archaeologists. One of the explorers who excavated at Nimrud in the 19th century was the British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard. Artifacts found during his expedition can be seen in the British Museum in London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. But any other artifacts and historical objects with stories to tell will remain unknown.

Temples in Palmyra

In May 2015, the terrorist group ISIS captured Palmyra, an ancient city in Syria that holds many archaeological ruins. Over the next eight months, ISIS plundered and destroyed a number of archaeological sites, including ancient temples dedicated to the gods Baalshamin and Bel.

The temples date back around 2,000 years and featured several massive, finely decorated columns. At the time the temples were in use, Palmyra was under Roman control. The city was becoming a hub for trade, bringing the city great wealth.

Peking Man

A series of fossils from a hominid species named Homo erectus pekinensis (more popularly known as Peking Man) were excavated in the 1920s and 1930s at Zhoukoudian cave in China. They dated back about half a million years. In 1937, Japanese troops invaded China; in 1941, the fossils were packed into crates in an attempt to ship them to safety in the United States. What happened afterward is unclear, but many scholars believe that the fossils were lost en route to America.

Despite the loss of the fossils, research into Peking Man is ongoing. A new series of excavations was conducted recently at Zhoukoudian cave, revealing that Peking Man was able to use fire, haft spears, work wood and design clothesthat provided protection during cold weather. The clothing and fire skills would have been particularly important, as research also indicates that Peking Man may have arrived in China as early as 780,000 years ago, when China's climate was colder.

Tenere Tree

Before it was destroyed, the Tree of Ténéré was an isolated acacia tree located in the Ténéré region of the Sahara Desert in modern-day Niger. The tree was supposedly the only tree growing for hundreds of miles and was arguably the most isolated tree on Earth. The uniqueness of the tree made it a landmark for people navigating the barren landscape.

The tree's roots ran down to the water table, and although the tree's age is not known, researchers presume that it started growing at a time when the Ténéré region was wetter. [What's the World's Oldest Tree?]

The tree met its end in 1973 when a vehicle collided into it. Reports suggest that the driver was drunk, although this claim is unconfirmed. Today, a metal sculpture of the tree stands where the tree once grew.

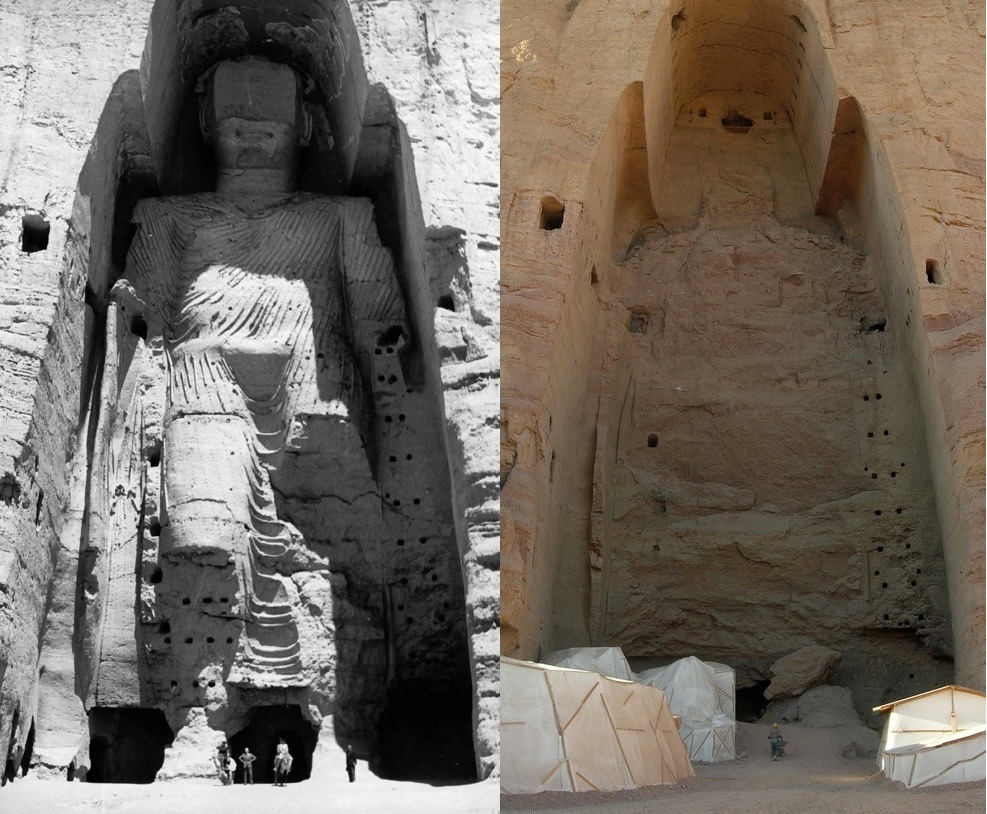

Buddhas of Bamiyan

Two giant Buddha statues stood in niches that were 180 feet (55 meters) and 125 feet (38 m) high at the Bamiyan Valley in Afghanistan. Dating back more than 1,500 years, they were part of "a large ensemble of Buddhist monasteries, chapels and sanctuaries along the foothills of the valley dating from the 3rd to the 5th century," the UNESCO World Heritage Site listingsays. [Photos of UNESCO World Heritage Sites]

In March 2001, the Buddhas were dynamited and destroyed by the Taliban, which, at the time, controlled most of Afghanistan. The Taliban were pushed out of the region at the end of 2001, and archaeological teams were able to excavate parts of the site that had not been destroyed. A light projection system has been used to recreate the image of the statues in the niches.

The image shows the taller Buddha of Bamiyan before (left) and after destruction (right).

Mar Behnam Monastery

The Mar Behnam Monasteryis located in Iraq near the city of Mosul and dates back to the sixth century A.D. Destroyed by ISIS in 2014, the Christian monastery contained architecture and inscriptions that stretched back over 1,500 years of history.

In the years before ISIS destroyed the monastery, Amir Harrak documented Mar Behnam's inscriptions and architecture. Harrak, a professor of Near and Middle Eastern civilizations at the University of Toronto, is now working with the Canadian Centre for Epigraphic Documentsto digitize the photographs and records of his research.

Pyramid at Nohmul complex

In 2013, a 100-foot-tall (30 meters) pyramid mound was bulldozed at the Nohmul complex, a ceremonial Maya site in Belize that dates back more than 2,000 years. The Associated Pressreported that it was bulldozed to extract crushed rock for a road-building project. The pyramid stood on private land and was protected by Belize laws that prohibit the destruction of ancient sites.

"They were using this for road fill," Jaime Awe, the head of the Belize Institute of Archaeology, told the Associated Press. "These guys knew that this was an ancient structure. It's just bloody laziness."

The Mantle Site

In both Canada and the United States, pressure to build housing and commercial space have led to the destruction of Native American archaeological sites that date back centuries. The Mantle Site— a 500-year-old Native American site in Whitchurch-Stouffville, Ontario, that held almost 100 longhouses — was excavated between 2003 and 2005. Then, the site was paved over to make way for a subdivision.

While the wooden structures of the longhouses were mostly decayed, the artifactsremained, and archaeologists were able to remove them from the site before it was destroyed. The site was located in Ontario, a jurisdiction that has been criticized for having lax heritage protection laws. Those laws were recently changed; if the new laws had been around in 2003, the site might have been saved, according to the archaeologists who excavated there.

Frauenkirche Dresden

A fantastic cathedral was constructed in the Baroque style during the 18th century in Dresden, in what is now Germany. Designed by architect George Bähr, the dome of the cathedral weighed 12,000 tons. Work began on the cathedral in 1722, and it took decades to complete; the sheer weight of the dome proved difficult to stabilize.

On the night of Feb. 13-14, 1945, the city of Dresden was subjected to a firebombing campaign by allied bombers meant to destroy German military units, installations, factories and workers' homes. The cathedral's wooden pews and galleries burned in the blaze, and the cathedral was subjected to extreme heat. Within two days, the cathedral had collapsed.

Historians have since argued over whether the bombing of Dresden was necessary. A new cathedral has been constructed, and its parishioners conduct extensive peace and reconciliation work.

Amber Room

The amber room was located in Catherine Palace(named for the wife of Peter the Great) in Tsarskoe Selo, near St. Petersburg, Russia. Constructed in the 18th century, the room contained mosaics, gemstones, mirrors, carvings gilded with gold, and panels constructed out of almost 1,000 lbs. (450 kilograms) of amber. The room's ornate decoration and beauty are difficult to describe in words.

Tsarskoe Selo was captured by Germany in 1941 during the invasion of Russia. The amber room was disassembled by German forces and transported westward toward Germany. Although archaeologists and historians have proposed many theories as to its whereabouts, the location of the disassembled amber room is still unknown. Today, a recreation of the amber room is located at Catherine Palace.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Why is yawning contagious?

Scientific consensus shows race is a human invention, not biological reality