Hyena Meets Tasmanian Devil: Ancient 'Hypercarnivore' Unearthed

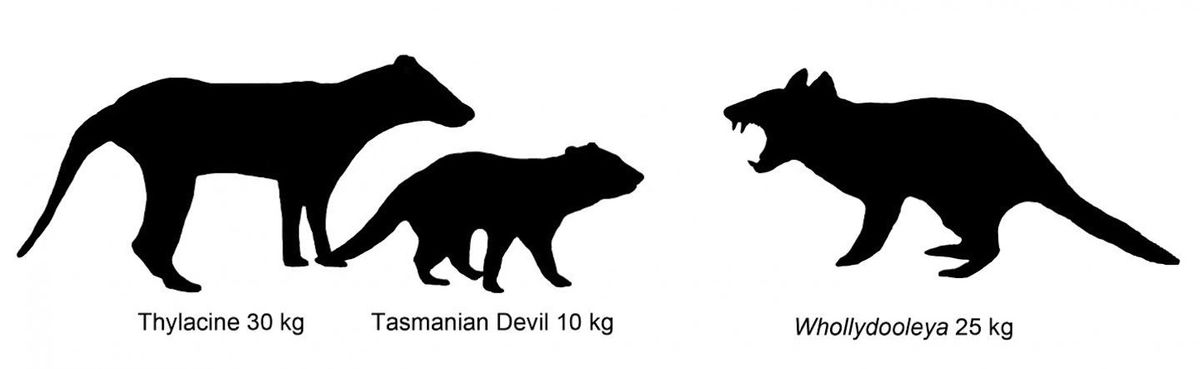

A newfound extinct marsupial "hypercarnivore" from Australia — one that researchers say looked like a cross between a Tasmanian devil and a hyena — was about twice as big as Australia's largest living flesh-eating marsupials, a new study finds.

Named Whollydooleya tomnpatrichorum, the predator is just one of a bevy of what scientists said were "strange, new animals"found in a fossil-rich site Down Under.

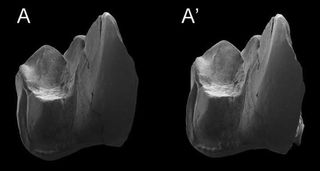

Although scientists have so far discovered only a single lower molar tooth of this predator, they deduced from the animal's tooth that "almost certainly it was a very active predator with an extremely powerful bite," said study lead author Mike Archer, a paleontologist at the University of New South Wales in Sydney. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

Judging from the size and shape of this fossil molar, the researchers suggest W. tomnpatrichorum was what scientists call a hypercarnivore. This term "generally refers to a predator that is larger than a cat whose diet is at least 75 percent meat," Archer told Live Science. "These are animals that specialize in killing and eating other animals, although they probably wouldn't pass up a juicy bit of fruit from time to time."

The scientists estimated that this hypercarnivore weighed at least 44 to 55 lbs. (20 to 25 kilograms). In comparison, Australia's largest living carnivorous marsupial, the Tasmanian devil, weighs only about 22 lbs. (10 kg).

A changing landscape

Back when W. tomnpatrichorum dwelledin the forests of northwest Australia during the late Miocene period, which lasted from about 12 million to 5 million years ago, Australia was beginning to dry out.

"Although Whollydooleya terrorized the drying forests around 5 million years ago, its own days were numbered," Archer said in a statement. "While it was at least distantly related to living and recently living carnivorous marsupials such as devils, thylacines and quolls, it appears to have represented a distinctive subgroup of hypercarnivores that did not survive into the modern world. Climate change can be a merciless eliminator of the mightiest of mammals."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Much remains a mystery about the animals from the late Miocene of Australia; fossils of land animals from this period are extremely rare because of Australia's increasing aridity back then, the researchers said.

"Fortunately, in 2012, we discovered a whole new fossil field that lies beyond the internationally famous Riversleigh World Heritage Area fossil deposits in northwestern Queensland," Archer said in a statement. "This exciting new area, New Riversleigh, was detected by remote sensing using satellite data."

Exploring Australia

This discovery "reminds us about how much of the Australian continent remains virtually unexplored," Archer said. "Much of remote, northern Australia has yet to be explored for potentially even more exciting paleontological deposits." [6 Extinct Animals That Could Be Brought Back to Life]

But these regions tend to be difficult to reach, Archer said. "We can't get vehicles anywhere near this area, hence we have to use helicopters, and they're very expensive," he added. The scientists began to carefully explore New Riversleigh in 2013 with the help of a grant from the National Geographic Society.

The new species' molar was one of the first fossil teeth unearthed from an especially fossil-rich site in the area, which study team member Phil Creaser discovered. This fossil-rich locale was named Whollydooley Hill in honor of Creaser's partner, Genevieve Dooley. The species was, in turn, named after Whollydooley Hill, as well as Tom and Pat Rich, "who are well-respected research colleagues," Archer said.

All in all, the site is yielding "the remains of a bevy of strange, new, small- to medium-sized creatures, with W. tomnpatrichorum the first one to be described," Archer said in a statement.

One strange feature of these fossil teeth is that they were often worn down, Archer said. This suggests there was abrasive dust in the hypercarnivore's habitat and that the plants some of these animals were eating in the late Miocene may have been tough and drought-resistant, he said.

Not alone

Previous research did unearth medium to large-size late Miocene animals in Australia, but "those deposits give almost no information about the small to medium-sized mammals that existed at the same time, which generally provide more clues about the nature of prehistoric environments and climates," study co-author Suzanne Hand, a professor in the School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of New South Wales, said in a statement.

In contrast, "the small to medium-size mammals from the New Riversleigh deposits will reveal a great deal about how Australia's inland environments and animals changed between 12 [million] and 5 million years ago, a critical time when increasing dryness ultimately led to the ice ages of the Pleistocene," study co-author Karen Black, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of New South Wales, said in a statement.

All in all, W. tomnpatrichorum's large size is an early sign of the trend toward gigantism seen in many lineages of Australian marsupials, Archer said. "These new discoveries are starting to fill in a large hole in our understanding about how Australia's land animals transformed from being small denizens of its ancient, wet forests to huge survivors on the second most arid continent on Earth," Archer said in a statement.

The Whollydooley site also contains signs of windblown sand grains, which are absent from the older nearby Riversleigh World Heritage deposits. These windblown sand grains suggest "that at least two aspects of a drier Australia were taking shape — less water and more wind," Archer said. "Today, windblown sand grains are a normal part of every deposit forming in almost the whole of the continent."

In the future, "we have to raise funds to continue the remote exploration and dissolve the bone-rich blocks that we recover during these explorations," Archer said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the July 30 issue of the journal Memoirs of Museum Victoria.

Original article on Live Science.

Most Popular