Fungal Disease 'Valley Fever' Is Often Misdiagnosed

A fungal infection called valley fever, which can cause mild to severe lung problems (including holes in the lungs), is often misdiagnosed because the symptoms can resemble those of the flu or other illness, experts say.

The misdiagnoses can lead to unnecessary medications that don't treat the fungal infection, according to new guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

The guidelines stress that primary care doctors should consider the possibility of valley fever in patients who have pneumonia or continuing flu-like symptoms if they live in or have visited the western or southwestern United States, where the fungus is found naturally in the soil.

"Valley fever is underdiagnosed, in part because past guidelines were directed to the specialists, whereas most of these patients initially see their primary care physicians, many of whom aren't aware [of] just how common this infection is," Dr. John Galgiani, lead author of the guidelines and a professor at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, said in a statement. "About a third of cases of pneumonia in Arizona are caused by valley fever," Galgiani said, and the illness has been on the rise in recent years, with a 10-fold increase in cases in the Southwest over the past decade.

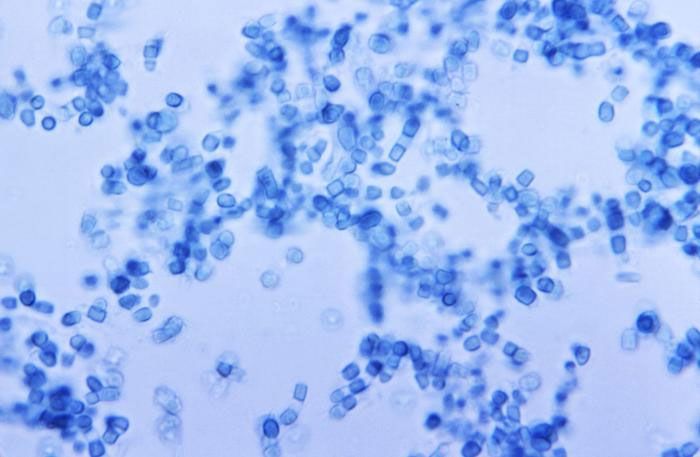

People get valley fever when they breathe in fungal spores, which can become airborne when the wind disturbs the soil. The fungus can cause a lung infection known as coccidioidomycosis. The fungus that causes the illness is found in desert regions, including western Texas, Arizona, northern Mexico and the central San Joaquin Valley in California. [10 Bizarre Diseases You Can Get Outdoors]

"It's an equal-opportunity bug, and everyone who is exposed has the same chance of getting infected," Galgiani said.

People with valley fever often have mild or no symptoms, but the infection can cause fever, fatigue, cough, headache, chest pain, skin rash and joint aches. In some cases, it can cause severe pneumonia, holes in the lungs, skin sores and meningitis (inflammation of the membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord.) People are at increased risk of developing complications from the illness if they are pregnant, have diabetes or are taking medications that suppress the immune system.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Each year, an estimated 150,000 people get valley fever, according to the guidelines. About 50,000 cases will result in an illness that needs medical attention, and of these 10,000 to 20,000 cases are diagnosed and reported, the guidelines said. Doctors who misdiagnose the illness may end up prescribing unnecessary antibiotic mediations, which will not treat valley fever.

About 50 to 80 percent of people with valley fever won't need medications for the illness, but they may benefit from physical therapy, and should check in with their doctor to make sure their symptoms aren't getting worse, the guidelines say. People who do need treatment will require prescription antifungal medications.

A new recommendation from the guidelines is that pregnant women with valley fever who are experiencing complications from the illness should take the antifungal medication fluconazole if they are in their second or third trimester of pregnancy. (The medication was previously not recommended because it may be toxic to the fetus in the first trimester, but it appears to be safe in the second and third trimesters.)

The new guidelines were published yesterday (July 28) in the journal Clinical Infectious Disease.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

2nd form of bird flu detected in US cows

New 'Camp Hill' virus discovered in Alabama is relative of deadly Nipah — the 1st of its kind in the US

Most Popular