Lessons From 10 of the Worst Engineering Disasters in US History

Tough lessons

Things don't always work the way they were intended to work. Sometimes those failures are almost imperceptible as they build incrementally, and other times, they happen in a terrible, overwhelming instant.

"You could argue, legitimately, that engineering is the study of failure, or at least consideration of ways to avoid it," said Benjamin Gross, the Associate Vice President for Collections at the Linda Hall Library in Kansas City, Missouri, which specializes in science, engineering and technology.

These catastrophes are reminders that "engineering is a human activity," Gross told Live Science. "Disasters of this sort aren't just based around the technologies."

And so, when calamity strikes, people often ask three questions: "What went wrong? Who's to blame? What could have been done differently?" Gross said. Given the complexity of modern engineering projects, answers can be hard to find, but they may influence and improve the next attempts to cross the great expanses.

Here are 10 of the worst engineering disasters in U.S. history.

Hyatt Regency walkway collapse (1981)

On July 1, 1980, the newly constructed Hyatt Regency Hotel in Kansas City, Missouri, opened to the public. The hotel featured several suspended walkways crossing its multistory atrium. Preliminary plans called for the fourth-floor walkway to hang from the ceiling, connected by steel rods. In that design, the rods would barely hold the weight of the walkway itself, and would not have passed local building codes. Those supports were included in the final construction, and to make matters worse, the second-floor walkway was suspended from the fourth-floor walkway directly above it, doubling the load on those parts.

On July 17, 1981, the hotel was crowded for a dance. The linked walkways crashed to the dancefloor, killing 114 people and injuring another 200 revelers. The structural engineer in charge of the walkways blamed the design flaw on a breakdown in communication, but the Hyatt Regency walkway collapse has become a popular case study in the ethics of engineering.

Johnstown Flood (1889)

On May 31, 1889, the South Fork Dam broke, unleashing 20 million tons of water from the artificial Lake Conemaugh. The city of Johnstown, Pennsylvania was 14 miles (23 kilometers) down the Conemaugh River, and the waters destroyed 4 square miles (10 square kilometers) of the city's downtown. In total, the flood killed 2,209 people, and bodies were later found as far away as Cincinnati.

The dam was owned by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, which counted many of Pittsburgh's financial elite among its members. In the aftermath, the tragedy was publicly blamed on the club's failure to properly maintain the dam, but courts maintained it was an "act of God."

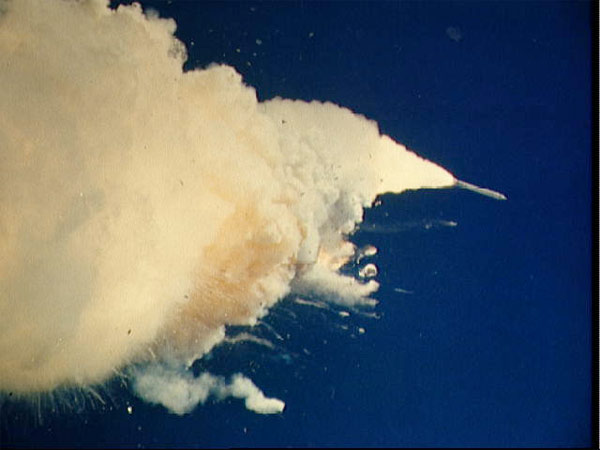

Space Shuttle Challenger (1986)

The 25th flight of the space shuttle Challenger, STS-51L lasted just 73 seconds on Jan. 28, 1986. Shortly after liftoff, smoke briefly appeared at a joint on the right rocket booster. After a minute, flames appeared near the same location and spread. Seventy-two seconds after launch, the shuttle was obscured by white smoke, followed by an explosive fireball. The seven crewmembers aboard Challenger were killed.

An investigation into the accident, the Rogers Commission Report, determined that the O-rings used in a joint seal on the rockets were inappropriate for the ambient temperature at the time of launch: 36 degrees Fahrenheit (2.2 degrees Celsius). In the cold, the rings reacted differently to the compressive forces of liftoff. The commission found that some engineers were aware of the issue, and had advised against launches in ambient air temperatures below 53 degrees Fahrenheit (12 degrees Celsius).

Tacoma Narrows Bridge (1940)

Spanning a section of the Puget Sound in Washington, the Tacoma Narrows Bridge became the third-longest suspension bridge in the world upon its completion in 1940. But its ambitious design — lighter, thinner and more flexible, with the deepest ever piers driven into the waters below — overlooked the winds that would often buffet the bridge.

Wind caused the bridge to move, creating an undulation that ran its length. When a cable snapped, that wave combined with a twisting motion, known as torsional flutter, that kept building upon itself. The bridge collapsed on Nov. 7, 1940, just four months after it opened to traffic. There were no human fatalities, but the accident spurred interest in modeling the effects of wind on large structures.

New Orleans Levees (2005)

When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans on Aug. 29, 2005, it killed hundreds of people and displaced many thousands more. The levees surrounding the city became a point of scrutiny in the aftermath of the destruction. A report from a team that included engineers from the University of California, Berkeley and the American Society of Civil Engineers identified several types of flaws in the levees soon after the hurricane hit.

As waters rose over the tops of levees, also known as overtopping, they eroded unprotected embankments on the other side, weakening the walls. Engineers also found weak points where different sections of flood protection met. Major breaches also occurred where it appears the levees may have been built on poor foundation soil that was vulnerable to storm surge.

The rebuilding of the levees, and with them the city of New Orleans, have sparked debate over how infrastructure should account for natural disasters.

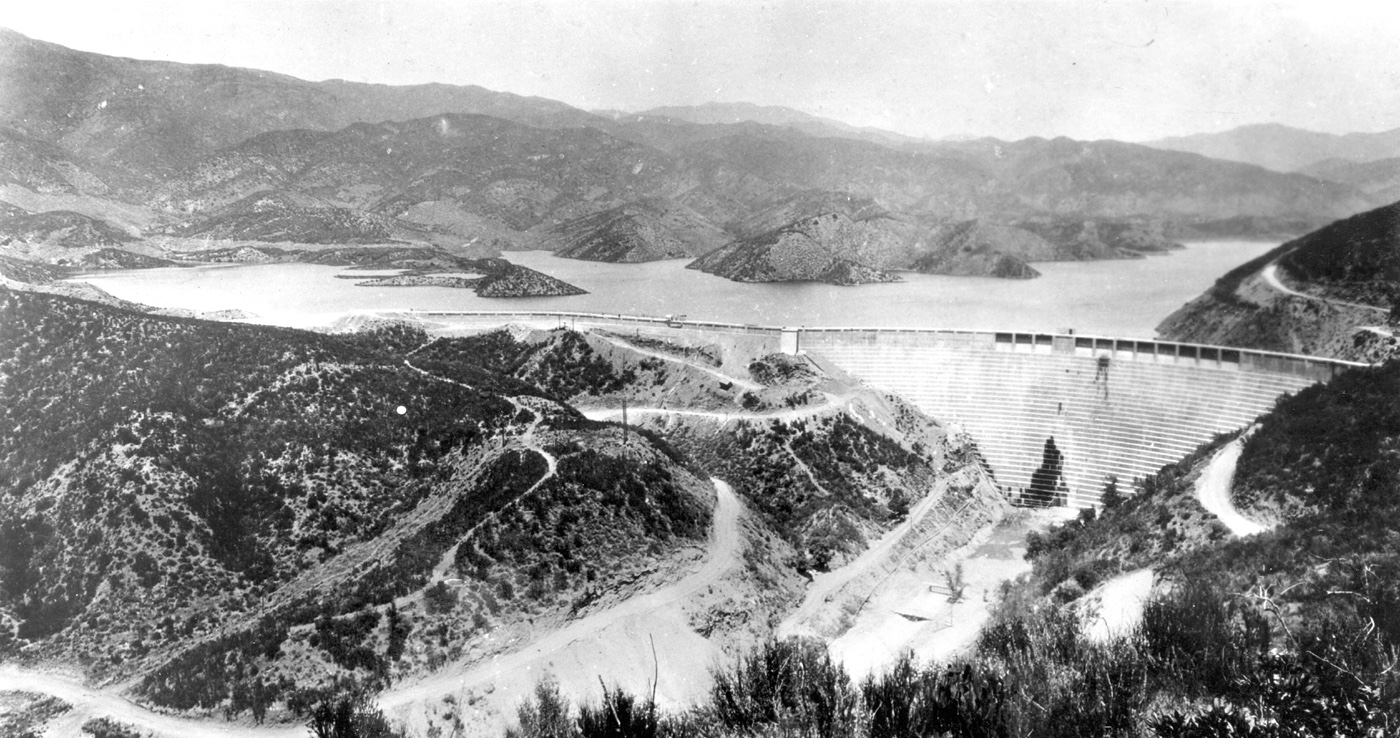

St. Francis Dam (1928)

The St. Francis Dam was completed in 1926 to provide water for the booming population of Los Angeles. Overnight on March 12, 1928, the dam failed, washing out its contents 52 miles (84 km) to the ocean. The accident officially killed 432 people, but an unknown number of Mexican migrant laborers were also caught in the flood zone. The failure of the St. Francis Dam has been called the deadliest engineering disaster of the 20th century.

Although there were aspects of the design and construction that would be questionable today, engineers didn't fully account for the geological features of the dam site. An ancient landslide created the chokepoint in the San Francisquito Canyon, which made it both an excellent location for a dam and a poor foundation for the structure.

Space Shuttle Columbia (2003)

The space shuttle Columbia launched on its 113th flight, STS-107, on Jan. 16, 2003. The day after launch, a scheduled review of takeoff footage revealed that foam debris from the external fuel tank had struck the left wing of the shuttle. Similar debris had been seen in previous takeoffs. Repeated requests to capture detailed images of the spacecraft in orbit to assess the extent of the damage were denied. On Flight Day 8, NASA's Mission Control informed the crew of the debris impact, and reported that there was “absolutely no concern for entry" with regards to the heat-resistant tile paneling on the shuttle's wing.

Columbia was scheduled to land on Feb. 1, 2003, after 16 days in orbit. As the shuttle re-entered Earth's atmosphere and passed over California, ground observers saw a bright trail of debris trailing the ship. By the time the space shuttle flew over Texas, communication with the crew was failing. Soon after, Columbia disintegrated midflight, killing its seven-person crew.

The Columbia Accident Investigations Board, set up to investigate what went wrong, concluded that organizational issues contributed to the fatal incident. The panel, which released its report in August 2003, made specific recommendations (such as better pre-flight inspection routines) to improve the safety of future shuttle flights.

Ford Pinto (1971-1976)

When the Pinto made its debut, the Ford Motor Company knew their new car design wasn't perfect. The fuel tank was easily punctured by nearby bolts, which left the vehicle susceptible to bursting into flames in the event of a rear-end collision.

But, the Ford Pinto, marketed for the model years 1971 to 1980, was conceived as an inexpensive, high-performance subcompact car, and that vision did not include safety as a selling point. And so, a decision was made, weighing the cost of $11 in parts per vehicle against the risk and expense of litigation over death and serious injury. The eventual adoption of new safety standards in the 1977 model year forced Ford to alter the design of the Pinto.

Three Mile Island (1979)

At 4:00 a.m. on March 28, 1979, a water pump in one of the nuclear power generators at Three Mile Island, in central Pennsylvania, malfunctioned. Some of the facility's safety procedures worked as intended — for example, a failsafe stopped the fission process in the reactor in response to an overheating steam generator — but workers forgot to open the valve for the emergency water pump after testing it just days earlier.

As a result, there was no water flowing to the steam generator (water creates steam for a turbine and cools parts of the generator). Eventually, the entire system overheated, causing a partial meltdown.

The accident exposed the public to some radiation, about 3- to 6-months worth of normal background radiation dose in the region, according to a report from Dickinson College. But during the tense 10 days until the situation was brought under control, public attention centered on fears of a more dramatic event, such as an explosion in the reactor.

Love Canal (1978)

From 1942 to 1952, a 2-mile-long (3.2 kilometers) ditch once planned as the beginnings of a canal was used as a hazardous waste landfill. In 1953, after dumping more than 21,000 tons of hazardous chemicals into the would-be canal, the Hooker Chemical Company covered the dump site in the Love Canal area of Niagara Falls, New York. Houses and a public elementary school were subsequently built in the surrounding acreage.

Over time, it became evident that the landfill had been managed improperly. In the 1960s, residents began noticing the effects of contamination. There were noxious odors and later, elevated rates of cancers and birth defects. In 1978, heavy rains unearthed leaking drums of chemicals, which pooled in foul, burning puddles throughout the neighborhood, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The response from the state and federal governments was unprecedented, and the site became influential in the acknowledgment of the public health threat posed by improperly stored industrial chemical waste. In 2004, the Love Canal site was removed from the EPA's Superfund List, which catalogues polluted locations that require long-term cleanup efforts.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.