5 Deadly Diseases Emerging from Global Warming

Reviving pathogens

As the globe warms, scientists warn about melting ice caps, rising sea levels and odd, extreme weather. But there's another threat that may already be emerging: New (and old) diseases spreading in places once thought safe.

Melting permafrost may release "zombie pathogens" that have been frozen in ice for centuries, while warming temperatures will allow disease-spreading insects to roam far and wide. Threats now confined to the tropics will likely become problems at higher latitudes. Here are a few of the diseases that could thrive in a warming world.

Anthrax, revived

In late July 2016, an outbreak of anthrax ripped through reindeer herds in Siberia, killing more than 2,000. A handful of people also fell ill. The culprit, according to local officials? A reindeer carcass from 75 years ago, which had remained locked in permafrost until bizarrely warm summer temperatures thawed the frozen soil and the corpse inside.

Anthrax is notoriously hardy. Its infectious spore form is surrounded by a protein shell that can keep it safe in suspended animation for centuries in soil, George Stewart, a medical bacteriologist at the University of Missouri College of Veterinary Medicine, told Live Science. Researchers have warned for years that burial grounds of anthrax-stricken cattle and reindeer in Siberia are ripe for triggering new epidemics, should the Siberian soil melt.

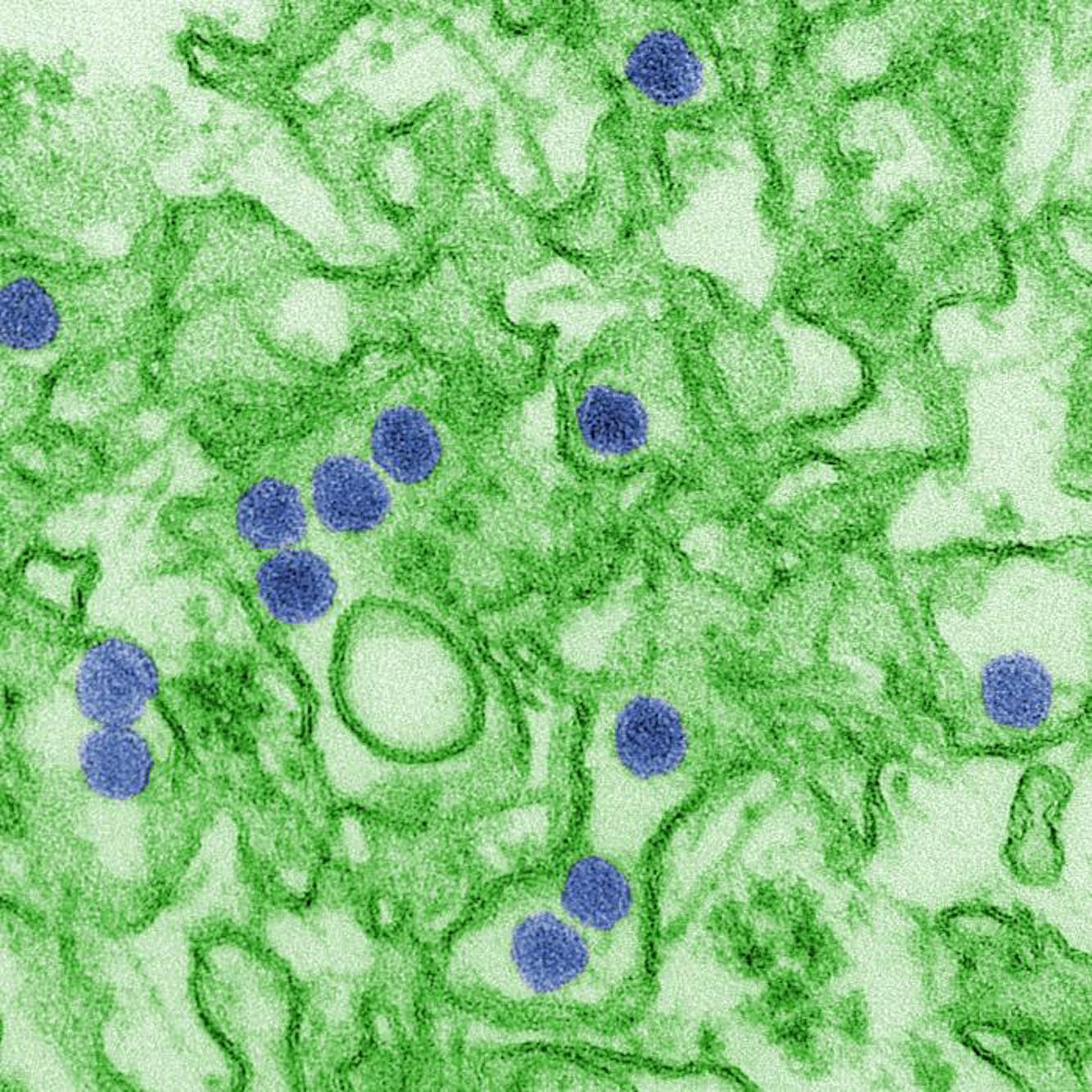

Zika shifts

Zika, a virus that typically causes no symptoms or mild fever and rash in adults, can be devastating when it infects pregnant women, causing miscarriage and microcephaly in fetuses. The main vector for Zika is the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which also carries dengue and chikungunya fevers.

A. aegypti is an urban dweller that bites in the daytime and can breed in a bottle-cap's worth of rainwater, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The mosquito is currently mostly found in the tropics, particularly in South and Central America, Southeast Asia and parts of Africa; in the United States, it's restricted to the southeastern states.

In a warming world, the distribution of these disease-carriers may spread. A 2014 paper in the journal Geospatial Health suggested that some tropical regions may become less welcoming to A. aegypti, while current safe places like inland Australia, southern Iran, the Arabian Peninsula and more areas of North America will become more mosquito-friendly.

There is reason to think that the spread of A. aegypti won't cause epidemics of dengue and other diseases in temperate climates because many developed countries have mosquito controls in place, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Even factors as simple as window screens can halt epidemics. On the other hand, regions where global warming will cause drought might see an increase in A. aegypti mosquitoes if people start collecting rainwater for use around the yard, according to the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Water collection containers can be fertile breeding grounds for these mosquitoes.

Zombie diseases

But anthrax isn't the only pathogen potentially biding its time in the permafrost. In 2015, researchers announced that a giant virus they'd discovered in the Siberian permafrost was still infectious — after 30,000 years. Fortunately, that virus infects only amoebas and isn't dangerous to humans, but its existence raised concerns that deadlier pathogens such as smallpox, or unknown viruses thought extinct, might be lurking in permafrost.

Human activities such as oil drilling and mining in formerly frozen Siberia could disturb microbes that have been dormant for millennia.

Tick-borne illness expands

Like mosquitoes, ticks will probably find new habitat as the climate warms — and they'll bring their diseases with them as they move. One emerging example is babesiosis, a tick-borne illness caused by the parasite Babesia microti. This disease is primarily found in the Northeast and the upper Midwest in the United States, and infections occur mainly in the summer, when ticks (and people) are most active. Longer, warmer summers could mean more people have the opportunity to come down with babesiosis, according to a 2014 paper in the journal Infectious Disease Clinics of North America.

Lyme disease, likewise, could spread into new areas as its tick vector moves northward. A 2008 article in the journal Ecohealth found that Ixodes scapularis, the main tick vector of Lyme disease, will have 213 percent more habitat in Canada in the 2080s, assuming climate change continues along its current trajectory. The ticks will likely move out of the southern United States and become more plentiful in the central part of the country, the researchers concluded.

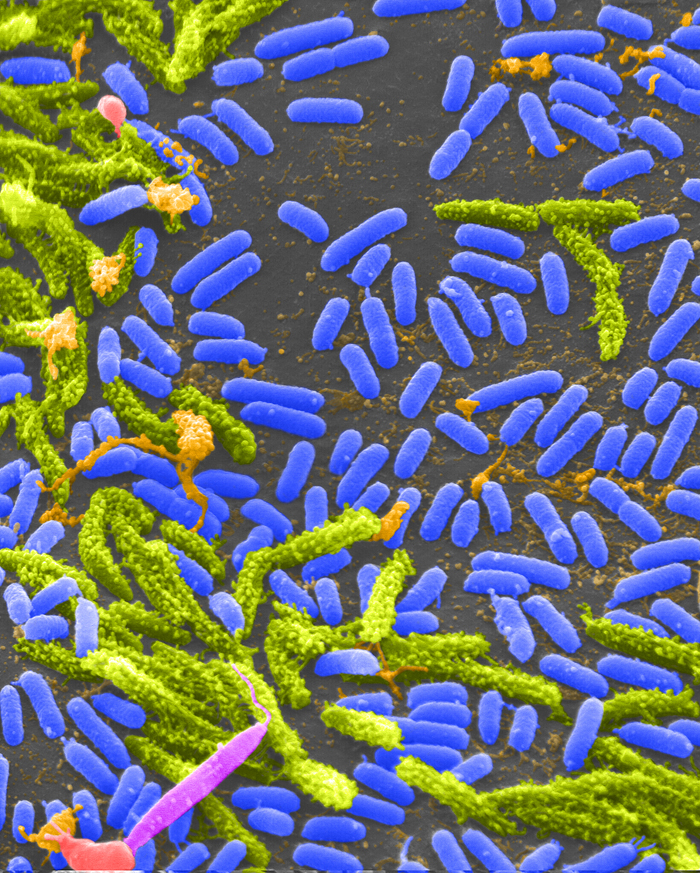

Cholera on the rise

The deadly diarrheal disease cholera spreads through contaminated water. In a warming future, research suggests, cholera outbreaks could increase.

A study presented in 2014 at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union found that increased heat and flooding caused by climate change could mean more cholera in areas already plagued by poor sanitation. Flooding can spread contaminated water far and wide, the researchers reported, while conditions of drought can concentrate lots of cholera bacteria (Vibrio cholera) in small volumes of water. At either extreme, it's a lose-lose scenario for public health.

"I would put cholera highest on my list to worry about with respect to climate change," David Morens, senior scientific adviser at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, told Think Progress in 2015. "Cholera likes warm weather, so the warmer the Earth gets and the warmer the water gets, the more it's going to like it. Climate change will likely make cholera much worse."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.