Teeny Radar Antenna Tracks the Flight of the Bumblebee

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

For the first time, scientists have tracked the flight paths of bumblebees over the span of their entire lives.

Not only do the results help biologists better understand bee behavior, but because the insects play a critical role in pollinating crops, understanding their movements could improve how farmers manage agriculture.

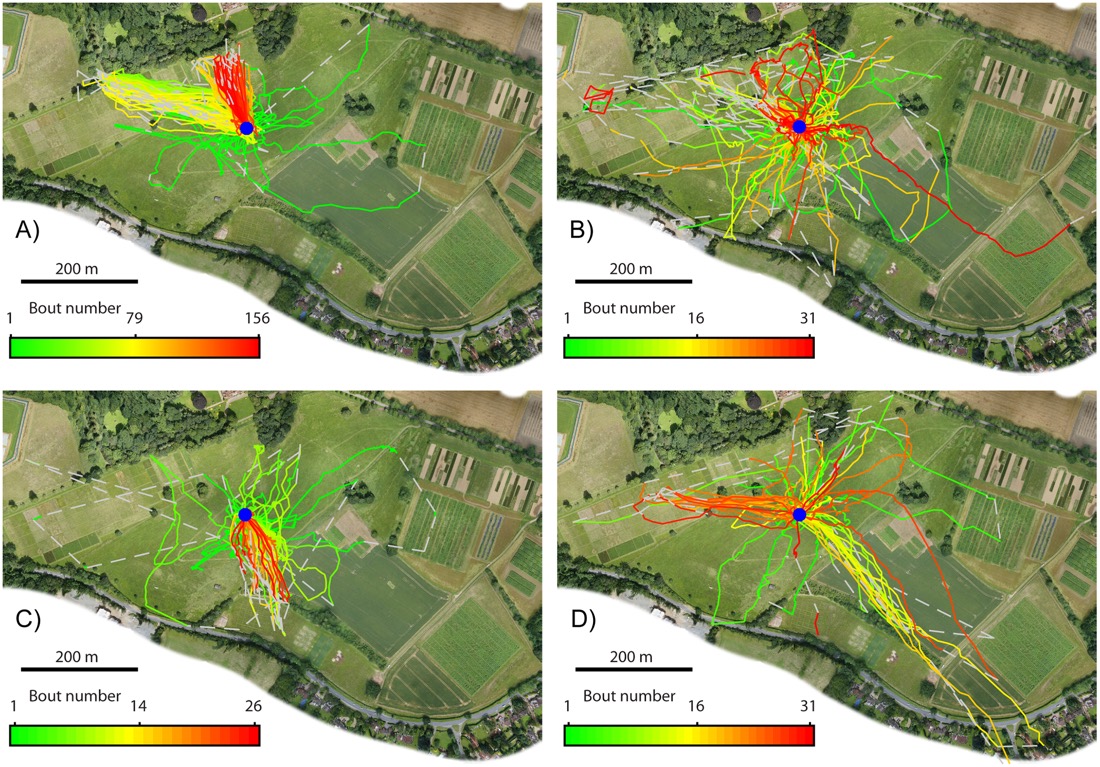

Joseph Woodgate of Queen Mary University of London and his colleagues used radar to monitor the daily flight patterns of four different bees, from the time they first left their nests to the time they ceased to return.

RELATED: Bee Backpacks Track Foraging

Because only one bee could be tracked at a time with the radar, the researchers set out four different colonies at four different times, tracking one bee each time.

"For the first time, we have been able to record the complete 'life story' of a bee," study coordinator Lars Chittka said in a press release. "From the first time she saw the light of day, entirely naive to the world around her, to being a seasoned veteran forager in an environment full of sweet nectar rewards and dangerous threats, to her likely death at the hands of predators, or getting lost because she has ventured too far from her native nest."

To monitor the insects, the scientists affixed a radar transponder just 16 millimeters tall to each bee using superglue. The antenna didn't harm the bee or interfere with its normal activities as it spent its days foraging a field of wild flowers and thistle in Hertfordshire, UK.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

From those four bees, the scientists gathered data from 244 flights, adding up to 15,000 minutes of flight and covering 111 miles.

RELATED: Top 10 Tricks for Pollinators

Previous studies had shown that foraging bumblebees tended to explore the area looking for food or exploit it, settling down to harvest. But how long they explored vs exploited was unknown.

"One of the most striking results to emerge," the researchers say in their paper published today in the journal PLOS ONE, "is the large degree to which our bees differed from one another."

For example, Bee 1 spent a much higher proportion of her time exploiting -- more than 90 percent. But Bees 2 and 3 spent more time exploring. Bees 1 and 3 didn't travel as far as 2 and 4 in their explorations. Bees 1 and 4 switched the destination of their flights over the course of their foraging and never returned to the first location they foraged.

RELATED: Pesticides Diminish Bee Sperm

The research sheds a little more light on a bee's life, which is short -- a month tops and most bees die much sooner. Bee 2 lasted just 6 days, the shortest life span of the bees in this study. On one occasion the scientists saw Bee 2 in the field after sunset, perched on a thistle stalk just below the flower. Bees don't fly at night and so it was there that she spent the night.

In the morning, the scientists returned before dawn and found her where they left her, sitting just below the flower. By 8:15 am, she was off again to forage for nectar.

On the sixth day, she made a fast, direct flight to the southeast, disappearing beyond the range of the radar. Maybe she found herself on a thistle stem as evening approached, strategy to forage again come sunrise. But a severe storm drenched the area overnight and she was never seen again.

Original article on Discovery News.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus