The first Americans may have traveled to their new home along the coast, new research suggests.

The findings clash with long-held views that the first Americans traveled through the interior of the continent from Siberia into North America, as textbooks have taught for decades. The new study reveals that a huge chunk of the interior land route was either devoid of food or sunk beneath a forbidding lake for hundreds of years after people from the Clovis culture showed up in the Southwest.

"It would have been a real barrier to cross," said study co-author Eske Willerslev, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Cambridge in England. [History's 10 Most Overlooked Mysteries]

Land bridge to Asia

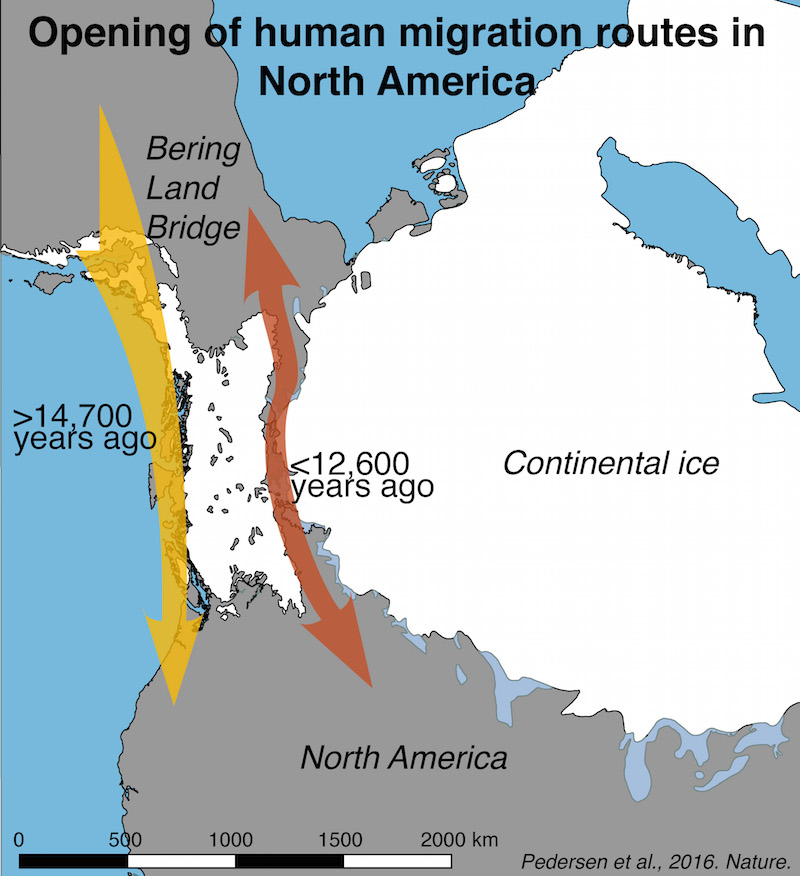

The conventional wisdom has been that ancient ancestors of today's Native Americans were trapped in the region of the Bering Strait for millennia during the last glacial maximum, when two huge ice sheets blocked the passageway into the Americas. Then, around 15,000 years ago, the ice sheets began to recede, and some of this population threaded its way through the narrow strip of land that was free of ice, thus entering North America.

However, in recent years that story has been called into question. Ancient Americans reached a site in southern Chile known as Monte Verde by about 14,700 years ago, and the ice sheets had probably not receded enough by then to allow interior passage, according to the study. Still, it's possible that the ancestors of the Clovis culture, who appeared roughly 13,400 years ago in North America, migrated through the continent's interior, Willerslev said. [In Photos: New Clovis Site in Sonora]

To see whether the Clovis culture may have used this interior route, Willerslev and his colleagues drilled samples of sediments from the bottom of the Spring and Charlie lakes in far northern British Columbia, Canada. During the Ice Age, this region was smack in the middle of the proposed ice-free corridor and was the site of a large glacial lake known as Lake Peace.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

No food, no route

The team analyzed DNA from pollen, plants and animals in the cores and found that, around 13,000 years ago, the ice-free corridor was either submerged under water or, even if it was above water, had no vegetation to burn for warmth and no bison. Given that, it's unlikely ancient people could have made the long trek into the heart of North America to found the Clovis culture, the researchers reported today (Aug. 10) in the journal Nature.

The first Americans were clearly curious explorers, but they were also realists, Willerslev said.

"We are talking [932 miles] 1,500 kilometers you have to pass with ice caps on each side. It's not like, 'Oh yeah, I'm just taking a three-day hike,'" Willerslev told Live Science. "Humans won't take the trip unless you have resources to sustain yourself along the way."

Instead, it's likely that the first people in America spread from what is now Siberia by hugging the coasts, Willerslev said.

Reasonable but not surprising

Though that finding may be a surprise for those who are wedded to their high-school history textbooks, experts have been leaning in this direction for years, said John Hoffecker, a paleoanthropologist at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research in Boulder, Colorado.

"It's not a big surprise," Hoffecker, who was not involved in the current study, told Live Science. The new paper "provides some hard evidence as opposed to mere speculation."

The ancient Americans probably both walked and used rafts or canoes to cover the distances they did in such a short period of time, said Justin Tackney, an anthropologist at the University of Kansas, who has analyzed the ancient Upward Sun River skeletons found in Alaska.

"Bouncing along the coast would move people much faster," Tackney, who was not involved in the current research, told Live Science.

Unfortunately, any archaeological evidence of these early migrations is likely submerged off the continental shelf in the ocean, Hoffecker said.

Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.