How Do Green Screens Work?

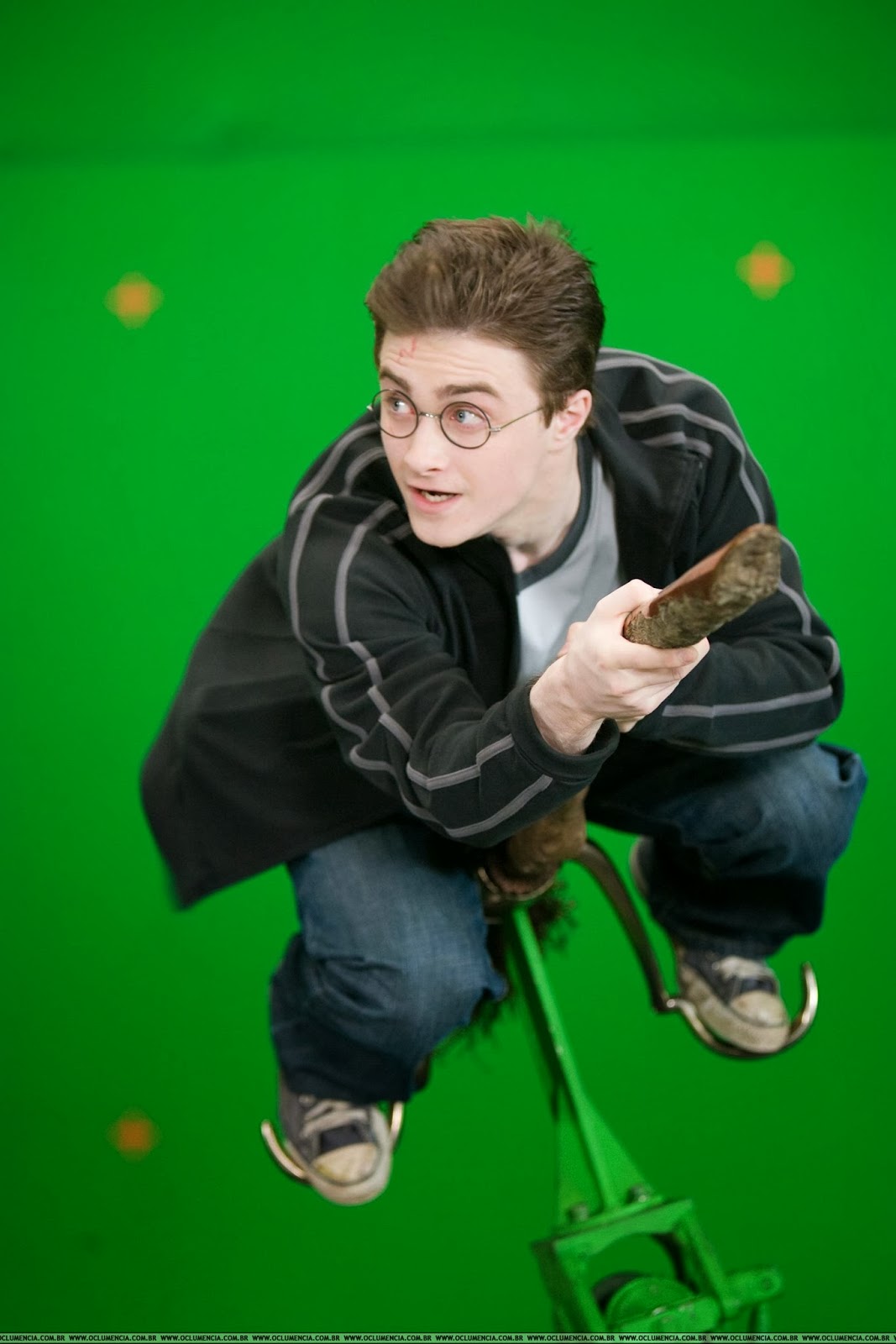

In movies and on television, actors walk — and sometimes fly — through elaborate and fantastic landscapes that simply don't exist in the real world. They ride on dragons' backs, grow crops on distant planets or visit magical realms with towering citadels inhabited by bizarre creatures. Sometimes the story takes place in a familiar city, but in the distant past — or the far-off future. Sometimes characters stage epic battles that seem to pulverize landmarks or places that audiences know well or where they live. And sometimes, the characters themselves are physically transformed, or defy the laws of gravity.

All of this high-tech fakery happens with the help of backdrops of brightly colored fabric or paint, and a process called "chroma key," also referred to as "green screen" due to the backdrops' color, which is typically a vivid green.

Chroma keying allows media technicians to easily separate green screens and panels from the people standing in front of them and replace those backgrounds with pretty much anything — from animated weather maps to the skyline of 1930s-era New York City to the icy Wall guarded by the Night's Watch in HBO's hit TV series "Game of Thrones." [Science Fact or Fiction? The Plausibility of 10 Sci-Fi Concepts]

The process takes recorded video (or digitally transferred film), a live video feed or computer output, and isolates and removes a single color in a narrowly defined region of the spectrum. The color is typically bright green or bright blue, because these hues differ so greatly from human skin tones and aren't usually found in clothing.

For the effect to work, green areas must be evenly lit and with no visible shadows, said Videomaker.com. Once green screens are identified and digitally removed, just about anything you imagine can be added back in, while the parts of the original image that aren't green remain unaffected. Chroma keying for live feeds requires hardware that can recognize and manipulate multiple video channels — layers defined by color — while recorded material can be changed in post production with video- or photo-editing software.

Chroma keying isn't just for backgrounds; it works with objects, too. Elaborate animated characters, such as the dragons in "Game of Thrones," often have bright-green stand-ins that the actors hold and interact with, but which the fully rendered animal replaces during editing.

Over decades, chroma key tech has become more sensitive and sophisticated. Improved edge detection and the capability to separate even individual hairs on foreground actors' heads from a green background makes integrating live action with spectacular effects more seamless and realistic than ever.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At the same time, digital technology has also become cheaper and more accessible, and chroma key is now within reach for anyone with a smartphone or tablet. Software and apps such as Photoshop, After Effects and iMovie make it possible for even amateur photographers or video editors to easily tweak and manipulate their own green-screen images — or those belonging to other people, with results that the original creator never intended.

Creative chroma key enthusiasts online were thrilled, for example, when England's Queen Elizabeth celebrated her 90th birthday by wearing a head-to-toe green outfit on June 11, 2016.

And on Oct. 8, 2015, when presidential candidate Jeb Bush tweeted a photo of himself testing a green screen used for weather forecasts, the internet response was swift, merciless and entirely predictable. A Reddit thread of the ensuing "Photoshop Battle" collected some of the best results.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.