Nearly a year after first making headlines around the world, "Tabby's star" is still guarding its secrets.

In September 2015, a team led by Yale University astronomer Tabetha Boyajian announced that a star about 1,500 light-years from Earth called KIC 8462852 had dimmed oddly and dramatically several times over the past few years.

These dimming events, which were detected by NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space telescope, were far too substantial to be caused by an orbiting planet, scientists said. (In one case, 22 percent of the star's light was blocked; when huge Jupiter crosses the sun's face, the result is a dimming of just 1 percent or so.) [13 Ways to Hunt Intelligent Alien Life]

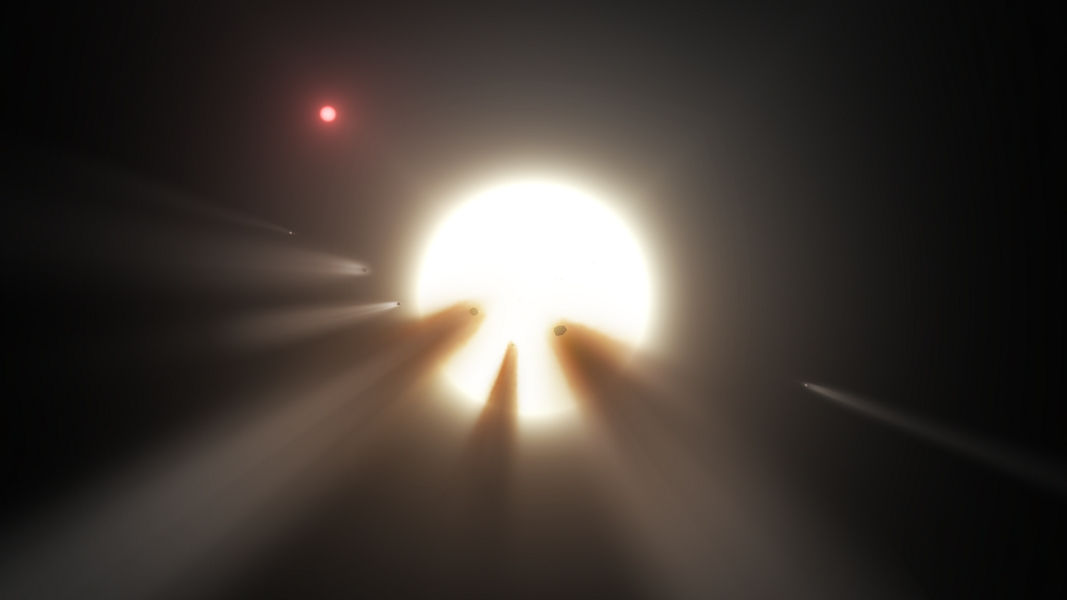

Boyajian and her colleagues suggested that a cloud of fragmented comets or planetesimals might be responsible, but other researchers noted that the signal was also consistent with a possible "alien megastructure" — perhaps a giant swarm of energy-collecting solar panels known as aDyson sphere.

Astronomers around the world soon began studying Tabby's star with a variety of instruments, and re-analyzing old observations of the object, in an attempt to figure out what exactly is going on. But they have yet to solve the puzzle.

"I'd say we have no good explanation right now for what's going on with Tabby's star," Jason Wright, an astronomer at Pennsylvania State University, said earlier this month during a talk at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute in Mountain View, California. "For now, it's still a mystery."

More surprises

That mystery may even have deepened over the past 12 months.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

![By surrounding their sta with swarms of energy-collecting satellites, advanced civilizations could create Dyson spheres. [Read the Full Dyson Sphere Infographic Here.]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/3P3DZiv9ya3FFxRnhxeZGn.jpg)

For example, in January, Bradley Schaefer of Louisiana State University determined that, in addition to the weird short-term dimming events, the brightness of Tabby's star had dropped by about 20 percent overall between 1890 and 1989 — a pattern very difficult to explain by known natural means, he said.

Schaefer came to this conclusion after poring over old photographic plates of the night sky that captured Tabby's star. Other researchers suggested that the trend Schaefer saw could have been caused by changes in the instruments used to take those photos over the century-long timespan. However, a new study bolsters Schaefer's interpretation.

In the new work, Benjamin Montet (of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena and the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusets) and Joshua Simon (of the Observatories of the Carnegie Institution of Washington) re-analyzed Kepler observations of Tabby's star from 2009 through 2013. They found that the object dimmed by 3 percent over that span, with a rapid 2-percent brightness dip over one 200-day period.

"Of a sample of 193 nearby comparison stars and 355 stars with similar stellar parameters, 0.6 percent change brightness at a rate as fast as 0.341 percent [per year], and none exhibit either the rapid decline by > 2 percent or the cumulative fading by 3 percent of KIC 8462852," Montet and Simon wrote in the new study, which they uploaded to the online preprint site ArXiv on Aug. 5. "No known or proposed stellar phenomena can fully explain all aspects of the observed light curve."

Schaefer's results, combined with those of Montet and Simon, make the comet hypothesis look less and less likely, Wright said in his SETI talk.

"Why would comets, over a century, make the star dimmer?" he said. "What's going on?" [5 Bold Claims of Alien Life]

Alien megastructure?

The sustained dimming of Tabby's star is still consistent with at least some variants of the "alien megastructure" hypothesis, Wright said.

"Some people have sort of facetiously offered that perhaps this is a Dyson sphere under construction: You're seeing lots of material getting built," he said. "In just 100 years, they've blotted out 20 percent of the starlight. That seems kind of fast to me, but, you know, aliens, right?"

It's also possible that the alien megastructure — if it exists — is fully constructed, and some parts are just denser than others, Wright added.

"That would naturally make the star get brighter and dimmer, as dense parts of the swarm came around," he said. "So if I had to invoke megastructures to explain it, that seems consistent. You've got lots of panels of different shapes, different sizes, and the big ones make big dips and the little ones make little dips, and the whole swarm is sort of like a translucent screen that makes the whole thing dimmer."

But Wright and others have always stressed that "E.T. did it" is a very unlikely scenario, and that a more prosaic explanation will probably rise to the top eventually. And indeed, other recent observations throw some cold water on the alien-megastructure idea — and any other hypothesis that invokes some object or phenomenon near Tabby's star.

Any structure surrounding the star, be it alien-made or naturally occurring, would heat up and give off infrared radiation, Wright said. But he and his colleagues saw no signatures of such "waste heat" in data gathered by NASA's Wide-Field Infrared Explorer spacecraft. And another research team — which analyzed observations by the Submillimeter Array telescope and Submillimeter Common-User Bolometer Array-2 instrument, both of which are in Hawaii — also came up empty.

Whatever is blocking the starlight from Tabby's Star is "not surrounding the whole star — it must be along our line of sight," Wright said. "So you can do that if it's in a disk of some kind. And that hopefully will help constrain what the heck is going on."

Wright has a hunch that the answer lies far away from Tabby's star, out in the dark depths of space.

"I think I've all but abandoned circumstellar explanations, and I think now we're going to have to talk about bizarre structure in the interstellar medium, and stuff like that," he said.

Still, Wright hasn't given up on the alien-megastructure hypothesis. While the lack of waste heat is "almost a fatal blow" for the idea, he said, it's still viable if the purported aliens are doing something with the waste heat — turning it into matter, for example, or converting the heat into radio waves for communication purposes.

Astronomers have already searched for such signals coming from Tabby's star using the Allen Telescope Array, a network of radio dishes in northern California operated by the SETI Institute. They found nothing. But Wright and his colleagues plan to conduct another search beginning in October; they've secured time on West Virginia's huge Green Bank Telescope for this purpose.

"This is a 1-in-300,000 object," he said. "People have gone looking for more, and it's the only one. So that also says you're allowed to invoke one really rare thing, because it is a rare phenomenon."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.