Lost WWII Ships Explored in Underwater Expedition

An exploration of a World War II battleground right off U.S. shores is now underway.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is working with several nonprofit and private partners to explore the twin wrecks of the freighter SS Bluefieldsand the German U-boat U-576. The German submarine attacked and sank the Bluefields on July 15, 1942, and was then itself sunk by bombs from U.S. Navy air cover and the deck gun of another merchant ship in the convoy, the Unicoi.

All hands were evacuated from the Bluefields and survived. Everyone on the U-576 — a crew of 45 — died.

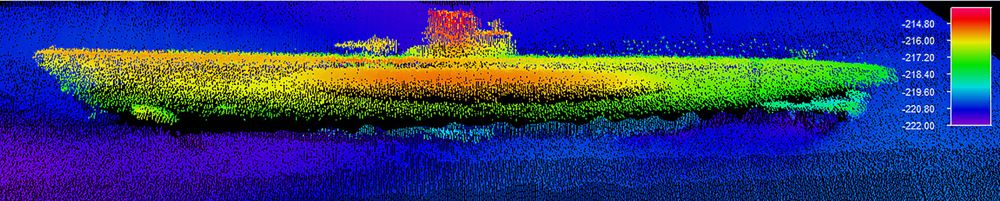

The precise location of the shipwrecks was lost until 2014, when an exploration by NOAA and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management discovered the two vessels 240 yards (219 meters) apart from one another off the North Carolina coast. The U-576 is a war grave; the German government stated in 2014 that it has no interest in recovering any wreckage or bodies and instead would be following the custom of viewing the wreck as a protected final resting place of any sailors within the submarine. [Photos: U-576 and the USS Bluefields]

New exploration

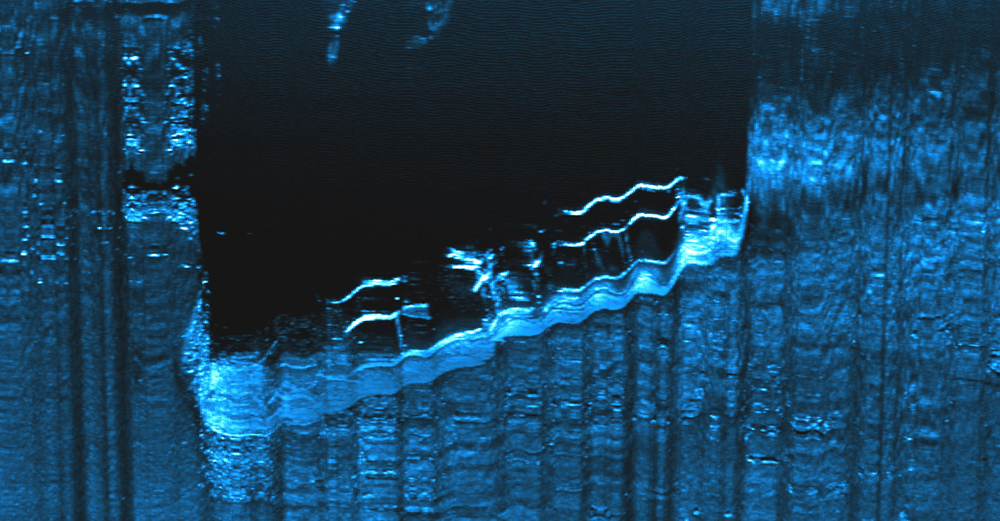

Now, researchers are taking a closer look at the two wrecks using manned submersibles. With support from the conservation nonprofit Project Baseline and the robotics and technology companies 2G Robotics and SRI International, NOAA scientists will gather visual, sonar and other data about the wreck sites until Sept. 6. Using this data, the University of North Carolina Coastal Studies Institute will build 3D computer models of what remains on the ocean floor.

"By studying this site for the first time, we hope to learn more about the battle, as well as the natural habitat surrounding the shipwrecks," Joe Hoyt, an archaeologist with the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary and chief expedition scientist, said in a statement.

The Bluefields was flying under a Nicaraguan flag with a military escort the day it went down, torpedoed by theU-576, which had been previously damaged and was limping back to Germany. The freighter sank in a mere 12 minutes, according to NOAA, and the U-boat's doom came soon after.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Answering questions, expanding protections

The new expedition to the wrecks is strictly observational, a NOAA spokesman told Live Science, and neither ship will be disturbed. Instead, researchers will take photographs and video and use remote-sensing methods to make bathymetric maps, which are like topographic maps for the seafloor.

Researchers will be looking into the details of the final battle for the two ships, the spokesman said. That includes investigating what sort of damage ultimately brought down the German U-boat and whether there is any indication the crew opened any of its escape hatches as the submarine went down, the spokesman said. The research team is also interested in the shipwrecks' second lives as artificial reefs off the North Carolina coast, where they may be sheltering fish species that are environmentally and commercially important.

The wrecks sit about 30 miles (48 kilometers) off the Cape Hatteras coast, outside of any marine sanctuary protections. The Monitor National Marine Sanctuary is nearby, closer to the coast, and protects the Civil War ironclad USS Monitor. It's possible that the boundaries of that sanctuary will be expanded to include the World War II ships, the NOAA spokesman said. The agency and its partners also plan to investigate other World War II wrecks in the area, including the E.M. Clark, a tanker sunk in 1942 by a German U-boat, and the Panam, another tanker lost to a U-boat torpedo attack, in 1943.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.