Photos: Amazing Microscopic Views of Italian Cocktails

Alcohol under the microscope

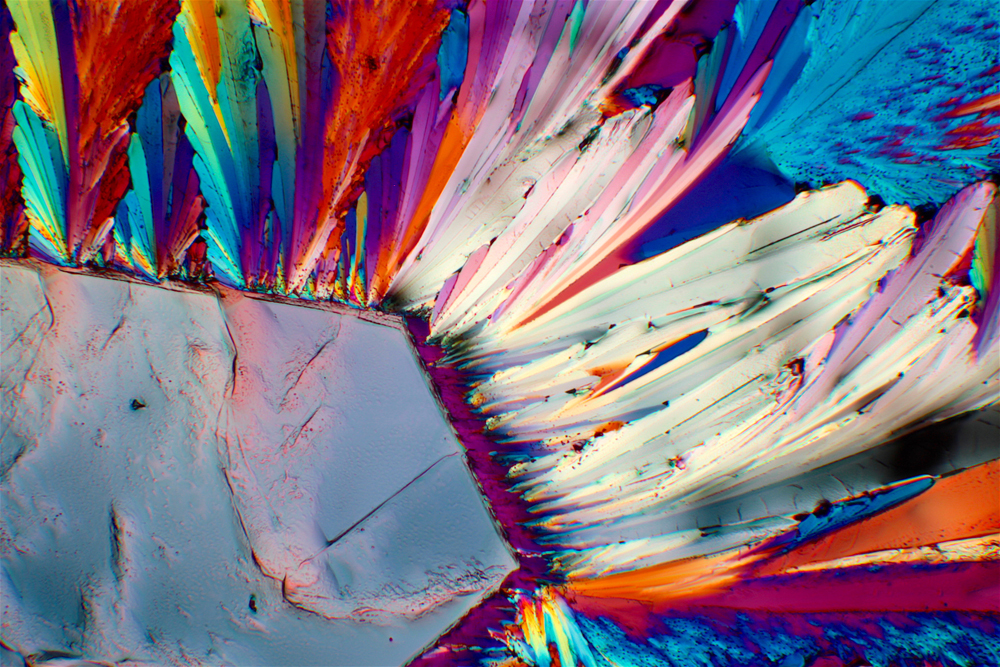

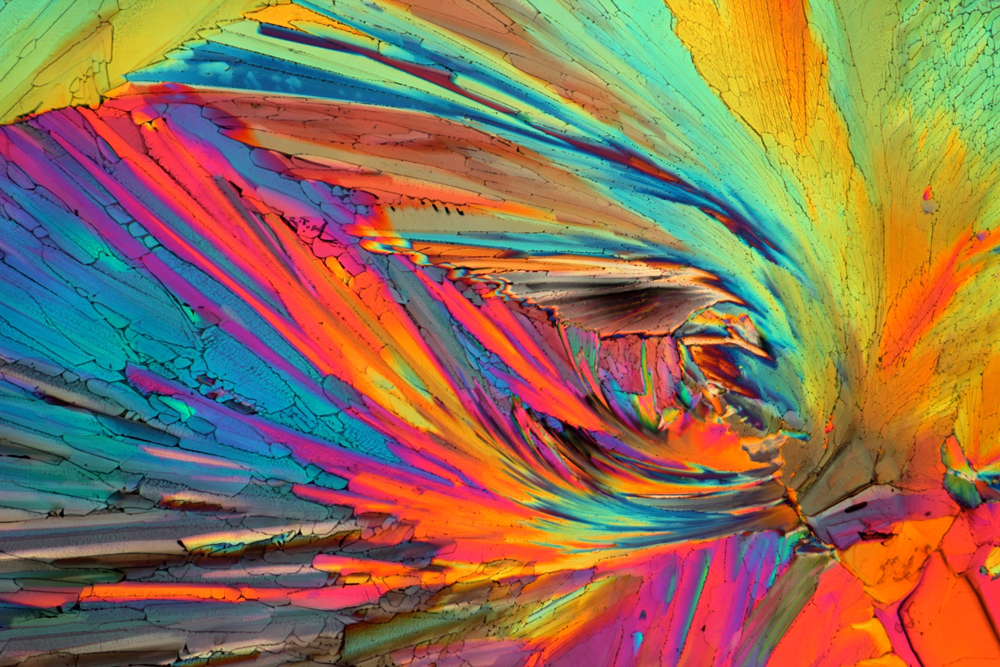

The feathery protrusions in this image don't come from some exotic bird. They're the Italian aperitif Aperol, a beverage that looks orange to the naked eye but erupts in a riot of color using polarized light microscopy. Italian geologist Bernardo Cesare has long used this scientific technique to examine the minerals in rocks. Polarized filters are placed above or below a thin slice of rock under a microscope. These filters bend the light, revealing crystalline structures in the sample that are otherwise hidden. The resulting colors can reveal the composition and formation history of a rock. [Read full story about the stunning microphotos]

Aperol sunbursts

Cesare was inspired to apply the microscopy technique to beverages by the photographer and Florida State University professor Michael Davidson, who created images of beer, bourbon, cocktails and more. (Davidson, in his day job, used microscopy to image cells using proteins tagged with fluorescence. He died in 2015.) Cesare admired Davidson's work, he said, but didn't want to copy his subjects until a friend suggested he try the technique on Italian beverages. Here, sugars from dried drops of aperol radiate in a sunburst pattern.

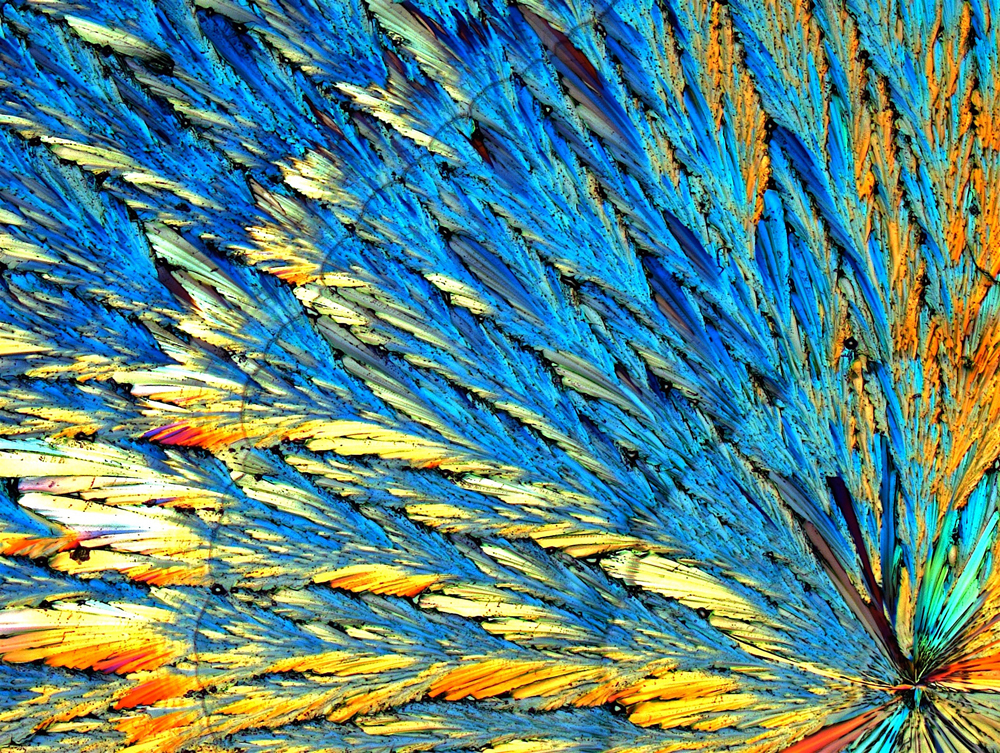

Crystalline sugar

The biggest challenge of photomicroscopy of beverages, Cesare told Live Science, is waiting for the drops to dry. That can take weeks. Aperol, shown here, failed to crystallize for about a month when Cesare first dripped some droplets on a glass slide. Then one day, the crystallization happened all at once. Each individual patch in this image is a crystal of sucrose, Cesare said. Colors reveal different orientations and thicknesses, while shape reflects the way the crystals grew.

Aperol in red and blue

Aperol is shown crystallized under a polarizing light microscope. One of Cesare's images was picked up for use in swimwear by the Australian clothing company Gypsea. He's also been featured in Infocus, the magazine of the Royal Microscopical Society.

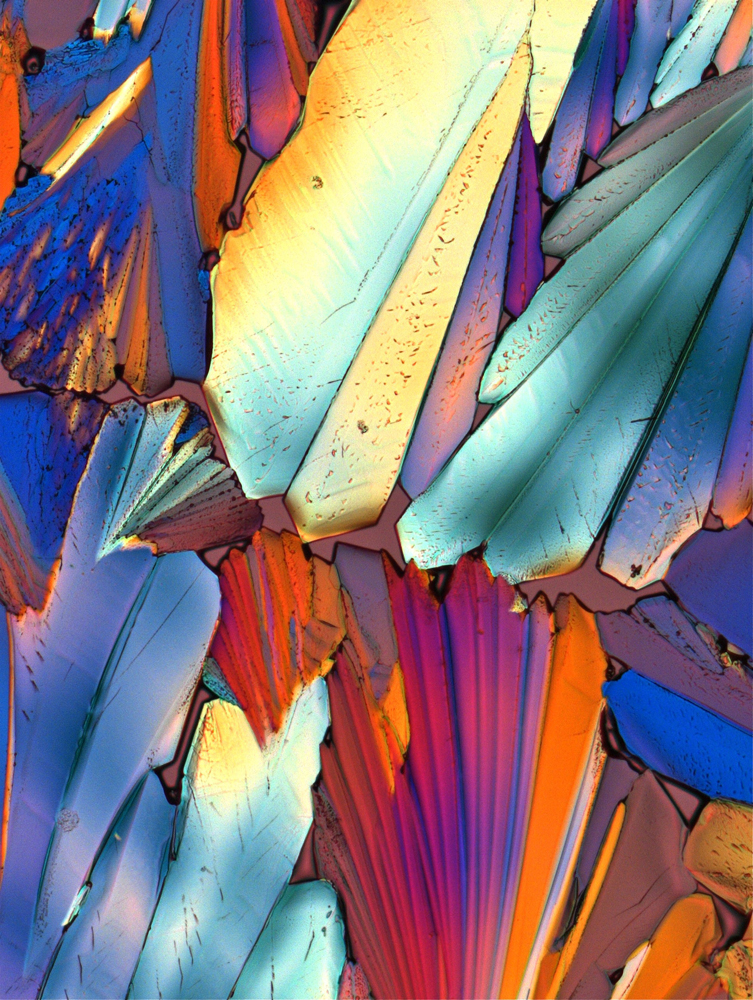

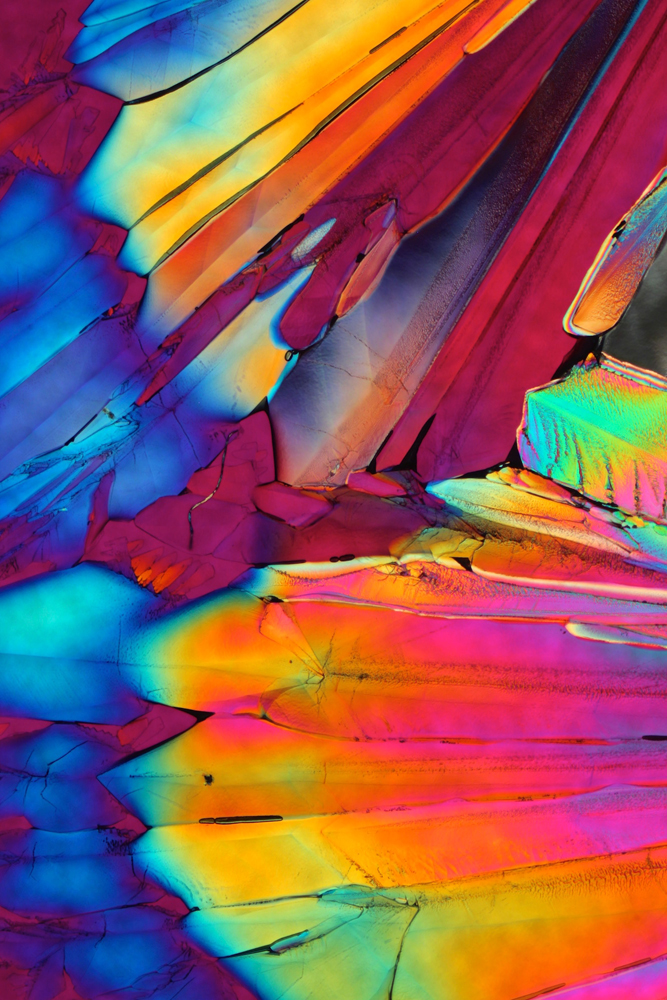

Butterfly wings?

Aperol crystals nestle together like butterfly wings in a microscopic image by Italian geologist Bernardo Cesare. The sugar in the beverage crystallizes as drops of the drink dry on a glass slide. Cesare then places the slide on a microscope between two polarizing filters, which bend the light to reveal the structure of the sugar crystals.

Rainbow in a glass

Aperol is less bitter and less alcoholic than its Italian cousin, Campari. It's made of bitter orange and herbs, and is a common ingredient in a northern Italian favorite, the spritz. Cesare was inspired to try photographing beverages by a colleague who suggested he see what a spritz (prosecco, seltzer and a bitter liqueur like Aperol) look like using polarized light microscopy.

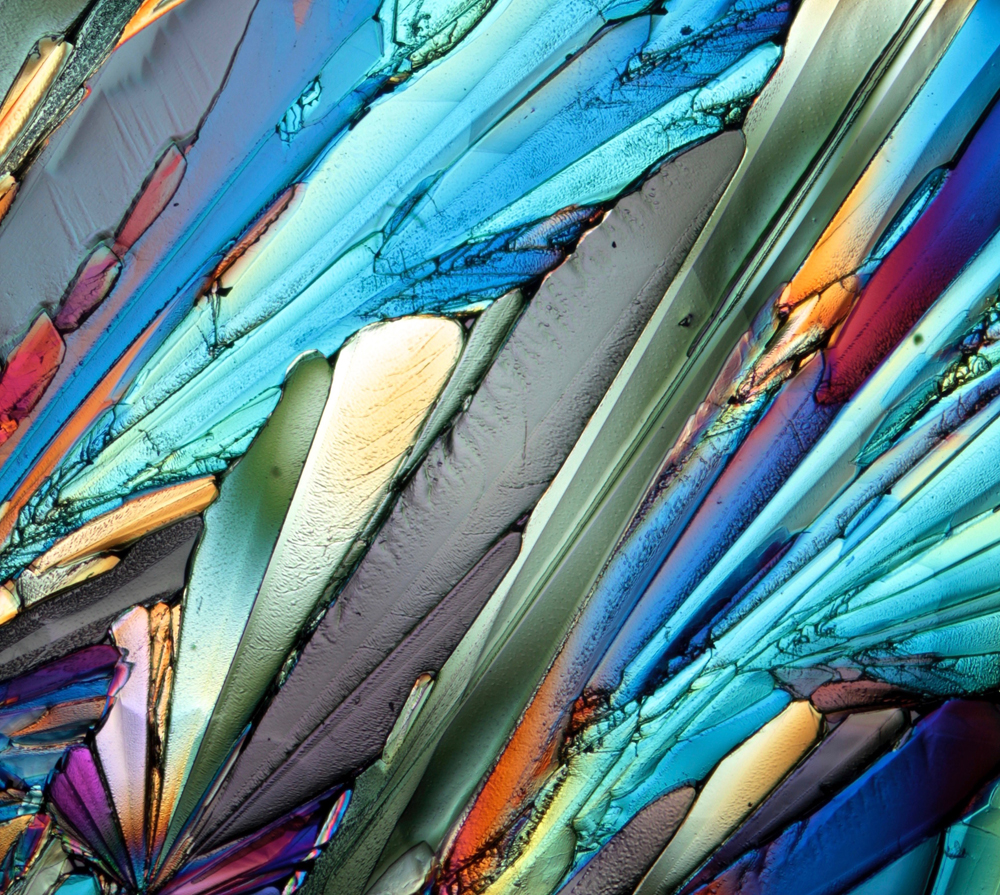

Colors in Aperol

An image of the Italian liqueur Aperol reveals faceted crystals of sucrose. The first microscopic beverage shots made with this technique by Michael Davidson were sold on a series of neckties during the 1990s.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

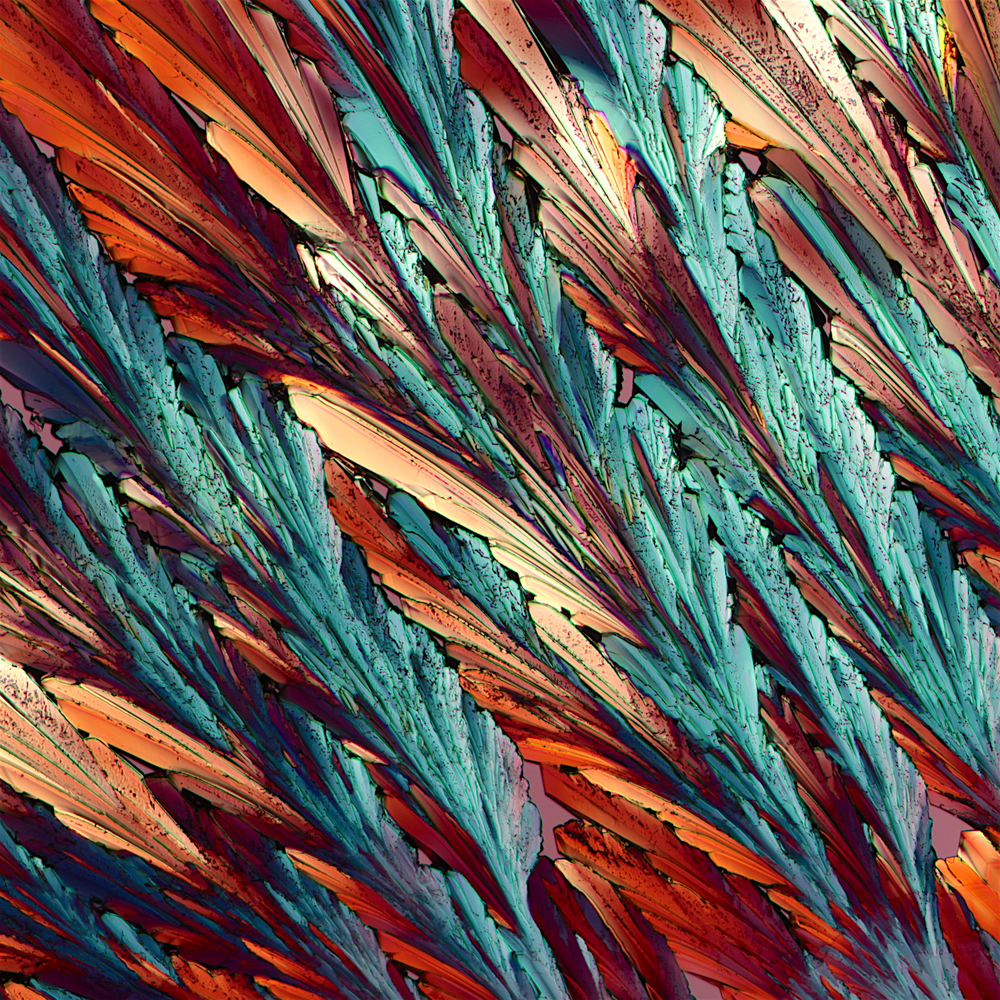

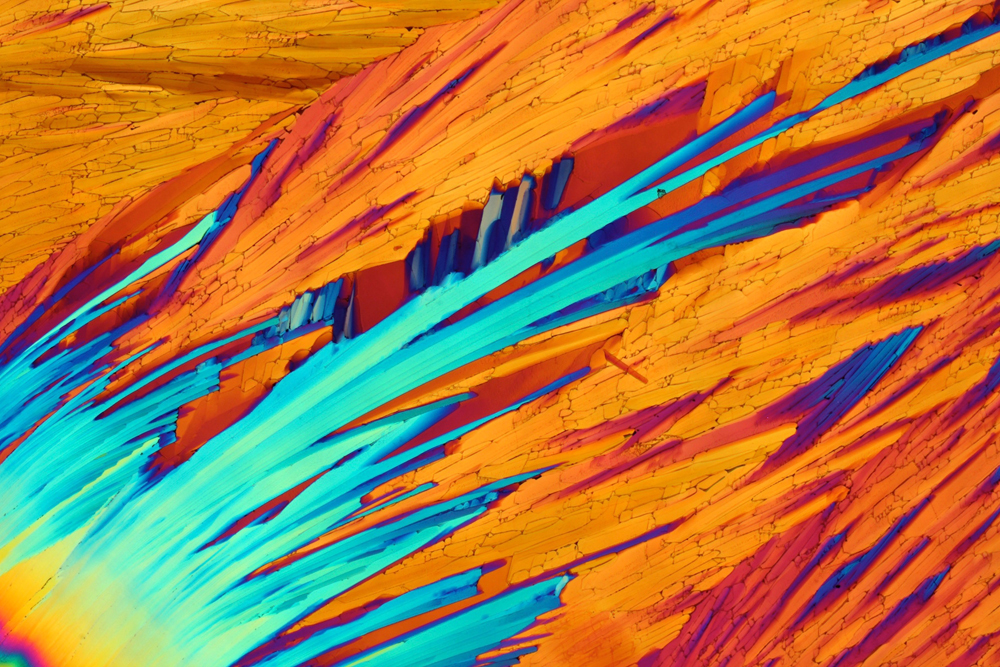

Colorful Campari

Campari is a dark-red liqueur made from citrus and herbs. It can be found in Italian spritzes, in the Americano and in Negronis. In Bernardo Cesaro's lab, it can also be found under the microscope. Here, dried crystals of Campari appear in orange and blue under polarized light.

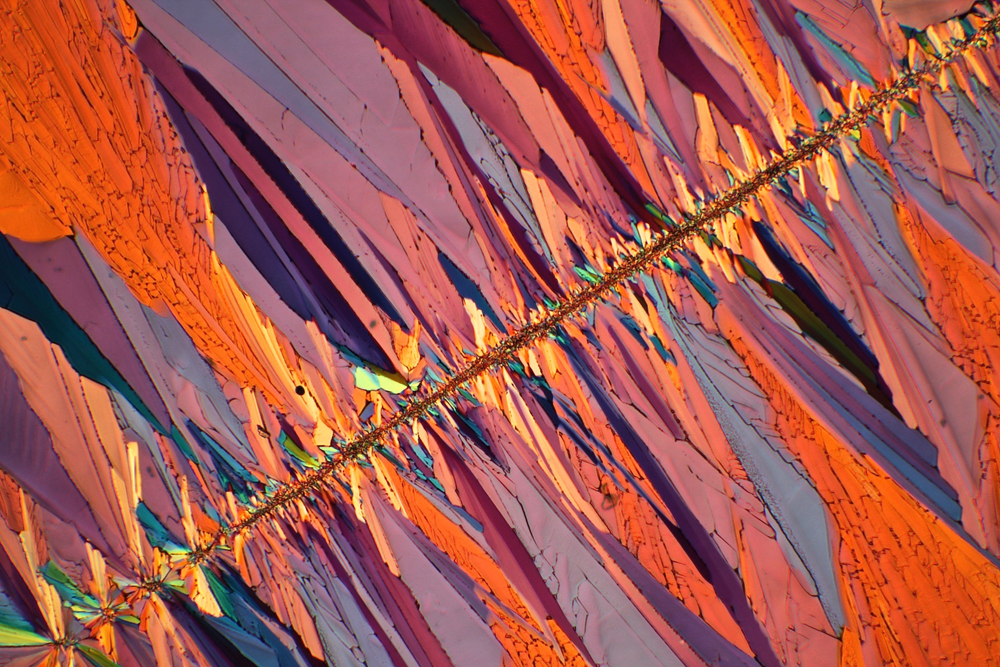

Campari crystals

Campari crystals emerge from a dense line of dried sugar. The shapes apparent in Cesare's images are due to the speed and direction in which the crystals formed. The colors aren't manipulated in any way except for a set of polarized lenses.

Riot of color

The photographer of these riotous Campari cystals is Bernardo Cesare, a professor of petrology at the University of Padova in Italy. In his day job, he studies metamorphic rock and alpine geology. Over the years, he's turned the photomicroscopy he uses onto the job into an art form, creating colorful images of minerals, drinks and even plastics.

Sugary wonderland

For polarized light microscopy, samples must be thin and transparent enough for light to pass through. Drops of alcoholic beverages, like the Campari seen here, dry to thicknesses of a few hundred microns. Rocks prepared for this technique are often sliced as thin as 30 microns, around half the thickness of a human hair.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.