Congressional Tweets Can Reveal Levels of Partisanship

SEATTLE — Elected Democrats and Republicans in Congress are often at odds with one another, and now there's a new way to directly measure that partisanship, new research finds.

The method is simple: Look at their tweets. Or, to be more precise, look for certain keywords in their tweets that may signal partisanship, said Jason Radford, a doctoral candidate in sociology at the University of Chicago, who did the research with co-author Betsy Sinclair, an associate professor of political science at Washington University in St. Louis.

With tweets, "you're actually getting a direct connection into what they're expressing" and what issues they fight for, Radford told Live Science. [7 Great Dramas in Congressional History]

In the study, the researchers examined more than 308,000 tweets from the 112th U.S. Congress, which served from January 2011 to January 2013. At that time, 89 percent of members had Twitter accounts, Radford said.

Moreover, the elected officials' accounts were quite active, putting out a total of 623 tweets per week on average, which means an average of six tweets per Congress member per week, Radford said.

To assess the level of partisanship within the tweets, Radford and Sinclair looked at which words were most commonly tweeted by the accounts of each party. For instance, Democrats commonly used these words: women, students, seniors, families, education, fight, health, proud, protect and #ACA, for the Affordable Care Act, the researchers found.

In contrast, Republicans were more likely to tweet these words: budget, cut, discuss, hall (for town hall), American, floor, nation, create, today, thoughts and district, Radford said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Then, the researchers looked at how frequently each member used these words in their Tweets, and made an algorithm that also prioritized the officials' personal accounts, as most members have different personal, official and re-election accounts, Radford said.

In all, the algorithm worked. Its ratings of the members' levels of partisanship closely matched the members' Poole-Rosenthal scores, a measure political scientists commonly use to calculate politicians' levels of partisanship levels based on their roll-call votes.

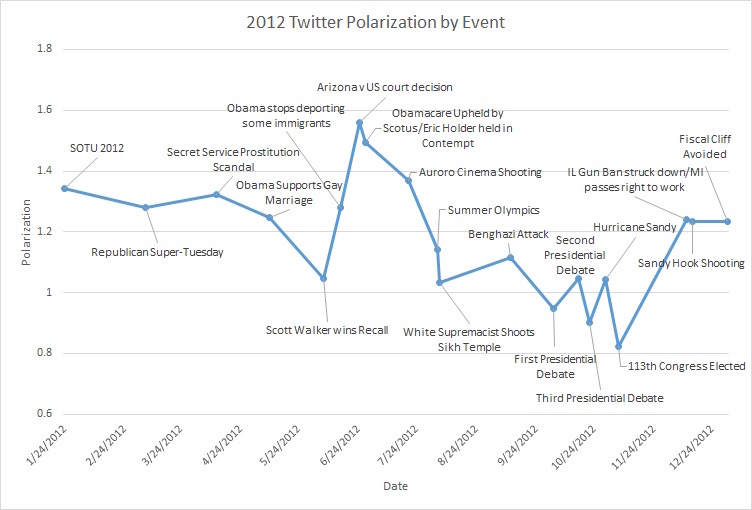

But roll call votes "occur relatively infrequently, while tweets occur hourly," Radford and his colleagues wrote in a draft report of their study. The researchers presented their study on Sunday (Aug. 21) at the American Sociological Association's annual meeting in Seattle. It has not been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

The algorithm also revealed which politicians were moderates, as these individuals used keywords from both parties, the research showed. And it revealed which issues were less divisive, such as legislation involving Cuba and the election of the 113th congress, Radford said.

He acknowledged "expressing an opinion on Twitter is not the same as voting on it legislatively." However, the tweets make it easy to track any changes in people's levels of partisanship in real time, for example, before and after a primary campaign, he said.

By measuring partisanship with the algorithm, "we can get a valid measure for every 10 tweets," Radford said.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.