Mock Mars Explorers Emerge from Habitat to End Year of Isolation in Hawaii

MAUNA LOA, Hawaii ─ A crew of six "astronauts" returned to Earth Sunday (Aug. 28), after a yearlong mock mission to Mars.

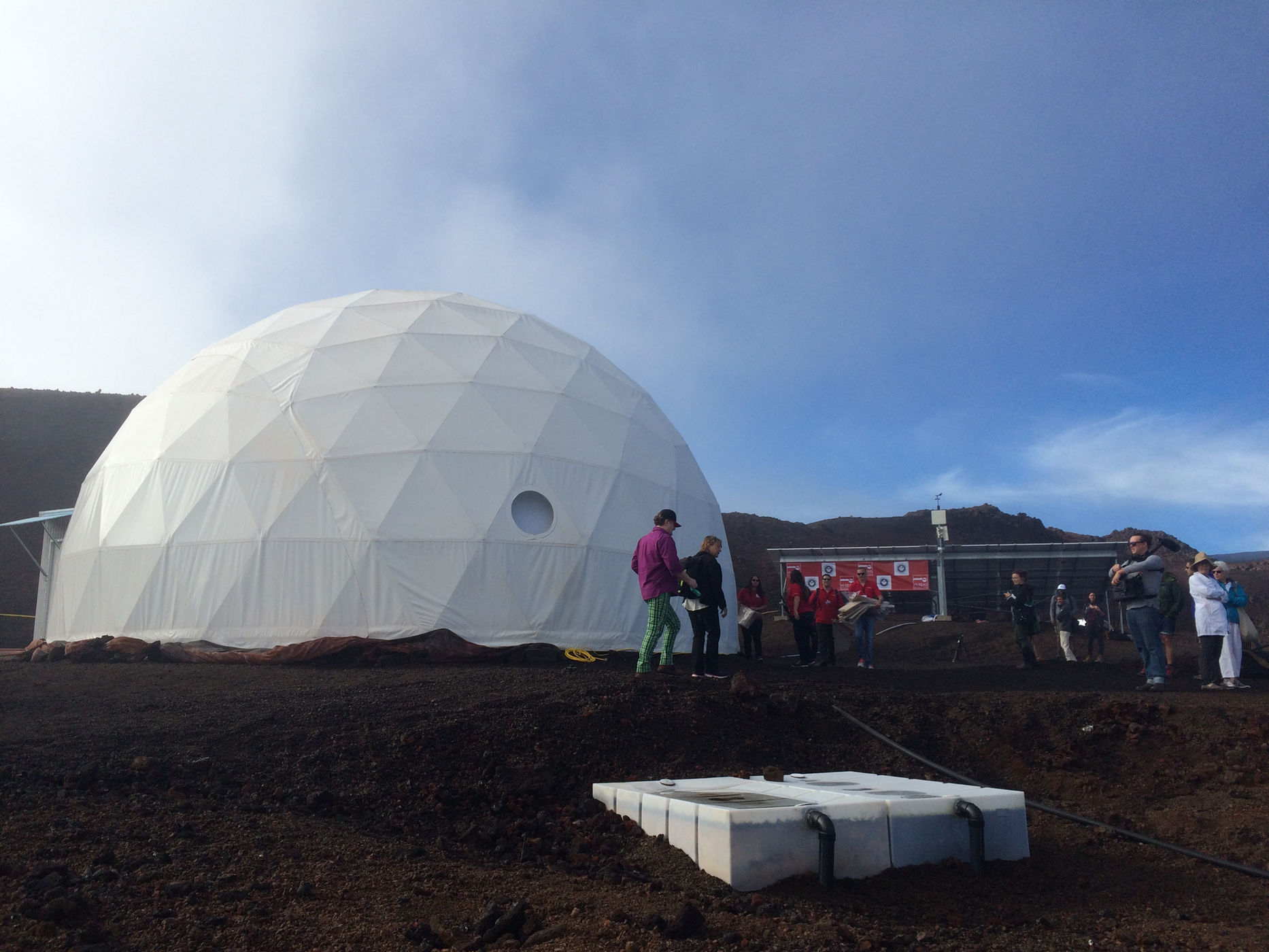

At about 9 a.m. HDT (3 p.m. EDT, 1900 GMT), on the barren slopes of the Mauna Loa volcano, the six crewmembers emerged from the domed white habitat they've called home for the last 12 months. The crew had no physical contact with anyone but each other, and had limited communication with friends, family and the outside world.

How did the crew feel upon their release? Christiane Heinicke, chief scientific officer and crew physicist, summed it up in one word: "Happyyyyy!" [HI-SEAS One-Year Crew Comes Back to Earth (Gallery)]

This is the fourth and longest isolation mission by the HI-SEAS program (which stands for Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation), run by the University of Hawaii at Manoa, and funded by NASA.

The crew exited the domed habitat for the first time in 12 months without wearing spacesuits, and were greeted by family, friends, the mission scientists and team members who supported them through the year, and members of the media.

"There's no place like Earth. It is a little bit like the tornado returning to Kansas," said Sheyna E. Gifford, chief medical and safety officer and crew journalist. "All of a sudden, I click my heels three times and stepped several inches, and 100 million miles later [I'm back on Earth]."

Andrzej Stewart, chief engineering officer, said he felt "mixed emotions" about leaving the habitat.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I'm a military brat, I grew up with my dad in the Air Force, and where you live becomes home after a while, and I'm going to miss the place," he said.

The HI-SEAS isolation missions (there have been four) are meant to simulate what life might be like for people living on the surface of Mars or another planet other than Earth. The participants can only eat food that can be stored for years at a time, so no fresh fruit and vegetables. Upon exiting the habitat, the crewmembers were greeted with trays of fresh produce. Heinicke made a beeline for a carton of fresh raspberries she'd requested.

The crew was able to communicate with family and friends, but with a 20-minute communication delay, making phone calls impossible; they can bring books and movies but have very limited access to the internet (text only).

Exercise has to take place on a treadmill or stationary bike inside the dome. The crew members can't leave the dome except while wearing spacesuits (these outdoor activities are what NASA calls Extra Vehicular Activities, or EVAs). [The 9 Coolest Mock Space Missions]

"We definitely took a couple of, like, 6-hour EVAs just to go and explore everything behind us, or go back into lava tubes or just anything to get outside really. Like we didn't really have an objective, it was just kind of to walk around and have fun. So that helps," said Tristan Bassingthwaighte, the crew architect.

Trouble in paradise

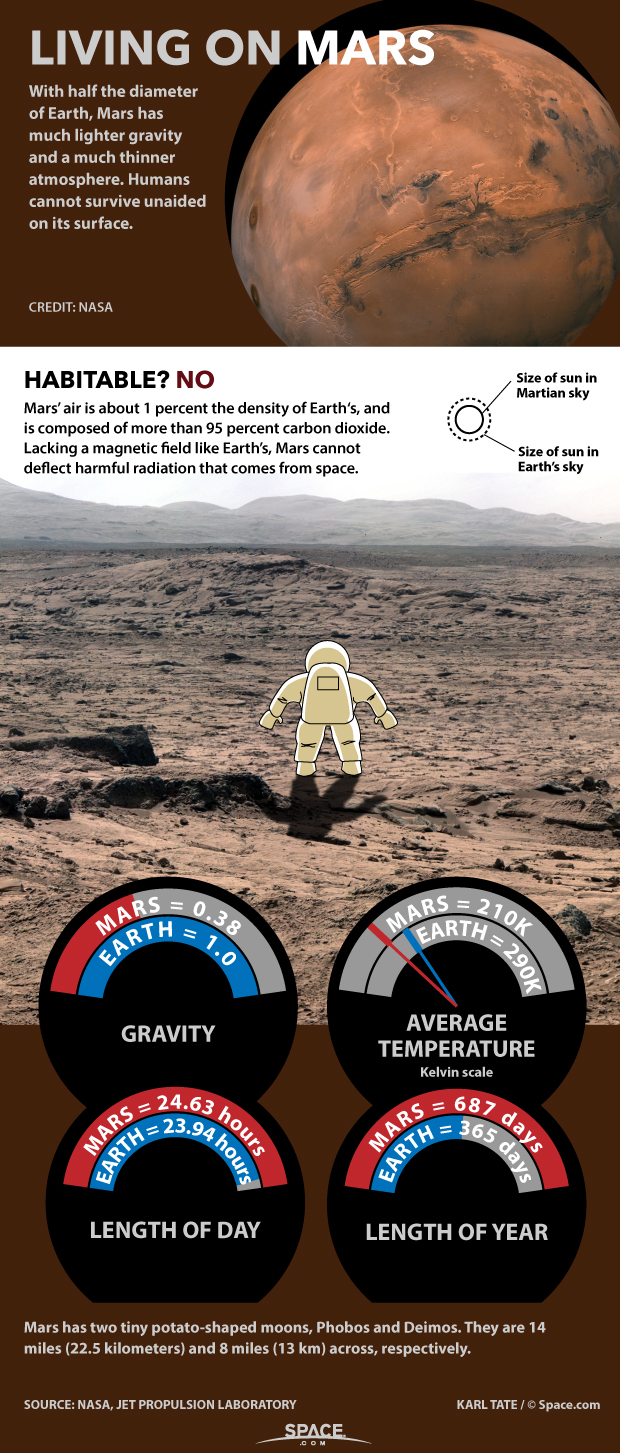

Living in an isolated, contained space with six people for 12 months is stressful on its own, but of course the crew faced some unforeseen challenges as well. [How Living on Mars Could Challenge Colonists (Infographic)]

"Probably the biggest [surprise] I can think of was not that long ago when our plumbing shut down," Bassingthwaighte said. The crew disassembled nearly the entire system and changed out parts they thought might be causing the problem. "[We] spent two weeks showering out of buckets trying to figure out what was wrong, and it turned out just to be a filter that we needed to replace, and we had water again."

Heinicke said the most challenging thing as a scientist was knowing she couldn't order extra parts or supplies for her laboratory if she needed them. Cyprien Verseux, the crew biologist, and Gifford, said they faced the same challenge.

"If your equipment breaks you can't just go to the supermarket or order it online and have it delivered in a couple of days," Heinicke said. "You have to be able to make do with whatever you have onsite, and you have to be able to improvise [with] your research. That, for me, was a challenge but also a challenge from which I learned a lot."

Carmel Johnston, the crew commander, said one of the biggest challenges was learning how everyone dealt with stress or depression.

"Everybody dealt with it in a different way, and so having somebody else deal with it in a different way than you can often be difficult, especially if you're not understanding why they are doing something the way they are," Johnston said. "Learning how everybody deals with stressful situations is really interesting, but also a learning experience."

Stewart echoed this sentiment and noted that the international nature of the crew (four Americans, one German and one Frenchman) could also lead to some misunderstanding about how people deal with stress.

"Yeah, so I'm German, I don't talk a lot," Heinicke said. "And these guys here, they are American, and they talk all the time." (This comment garnered a laugh from her crewmates).

Building a crew for Mars

The HI-SEAS program initiates these isolation programs to learn about the experience that humans will have when they set up long-duration camps on other planets (or moons, or what have you). The primary science objective of this yearlong mission was to learn about crew cohesion, and how people might best deal with the psychological toll of a real mission.

So what makes a good crew for a planetary space mission?

The answer may lie in a classic line from literature, according to Kim Binsted, project principal investigator for HI-SEAS. She said that while studying the HI-SEAS crews, she was reminded of the opening lines from the novel "Anna Karenina" by Leo Tolstoy: "All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." [How Astronauts May Set Up Base Camps on Mars (Gallery)]

"The crews, when they're working well — and they're very good crews, they're very competent and professional and cohesive — when they're working really well, they're very similar to each other," Binsted said. "But each crew has its own very particular conflicts."

Binsted can't talk about specific conflicts that arose in the one-year crew, both to protect crew confidentiality and because the scientific teams that study the crewmembers are still analyzing their data.

"I think, in a perfect world, NASA would have liked us to come back and say … 'The thing that causes problems in crews is X.' But that's not the case," Binsted said. "I think instead what you find is there's going to be conflict on these long-duration missions. It just happens. So what you want instead is both individuals and teams that are resilient; that are able to come back from conflict and get back to a high-performing level. And that's something that you can both select for and train for. So I think that's the big picture."

As the mission leader, Johnston said she felt a certain responsibility to help crewmembers keep their spirits up (in addition to making sure all the work got done around the habitat).

"It was definitely difficult at times, especially if I wasn't in that mindset myself," she said. "Because for whatever reason, everybody has bad days, or everybody has something that's upsetting them, and trying to cheer somebody else up when you're, like, 'I'm dealing with my own stuff right now,' is pretty difficult."

Besides the normal ups and downs, at least two of the crewmembers told reporters they had deaths in their family while they were away.

"I think we all kind of filled in at different times, and so we were all able to work together in order together to be like 'OK, so-and-so's having a rough time with whatever's going on in their life,' and we all pick up the [slack]," Johnson said. "And then, the next person has something fall down and you just kind of have a rotating roll of who gets to take a little bit of time off because something else more important in their mental life is going on."

In what is perhaps a reflection of Binsted's observation that each crew has its own unique conflicts, Johnston said her crewmates told her she was a neat freak — which came as quite a surprise.

"I apparently learned that I'm a neat freak, which I'm being honest about because apparently it's a big deal to everybody else," she said with a laugh. "I've never been told in my life that I was a neat freak, and my parents were always telling me when I was younger to clean up more and I always thought I'm just a slob. But it took living with people that have different standards to figure it out."

Tips for Mars

So after a year living together in isolation and containment, what would the HI-SEAS crew tell astronauts headed to Mars or some other destination?

"[Bring] a Kindle," Bassingthwaighte said. "Yeah, as many books as you can; movies tend to get really boring."

"I think telling your family to pack something nice, just a couple of letters that you can open on specific dates, that's a very good idea," Heinicke added.

"Remember your crew is the most important thing, they're all you've got," Gifford said. "So keep yourself healthy, keep them healthy."

"Bring a ukulele," Verseux said. "No, seriously, playing music helps a lot and, like, a guitar is too big and a ukulele's perfect." (Verseux apparently also brought a digeridoo).

Would the crew go on a real Mars mission if they were given the chance?

All six immediately replied, "Yes."

Editor's note: Calla Cofield is visiting Hawaii and the HI-SEAS mock Mars habitat on a trip paid for by the National Geographic Channel's "Mars" miniseries.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.