Human Ancestor 'Lucy' May Have Died After Falling from Tree

"Lucy," the iconic 3.18-million-year-old early human, literally dropped dead, according to new research that determined she died of injuries sustained after falling from a tall tree.

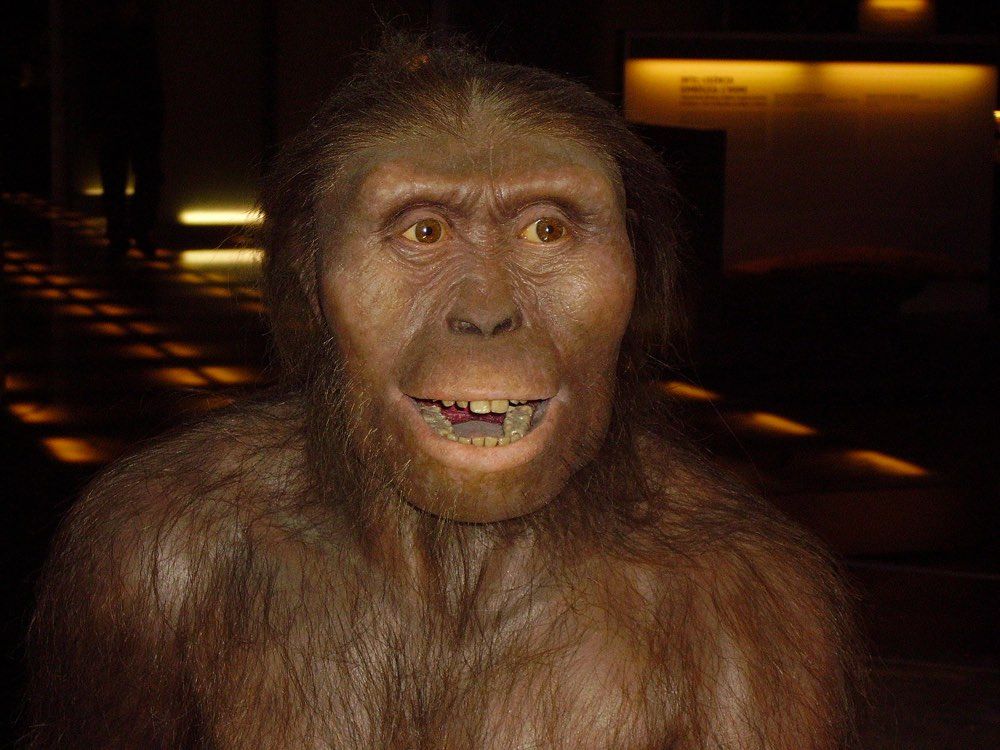

Since Lucy's species Australopithecus afarensis existed within a transitional period when our primate ancestors evolved from a more tree-dwelling lifestyle to a terrestrial one, the new findings — published in the journal Nature — indicate that adaptations that made it easier for our ancestors to walk on two legs on land compromised their ability to climb trees safely and efficiently. This may have predisposed them to falls from heights, as what may have happened to unfortunate Lucy, whose broken fossilized bones tell nearly the whole story.

"Today these fractures are often seen in automobile accidents, but also an impact following a fall from height," lead author John Kappelman, a professor of anthropology atThe University of Texas at Austin, told Discovery News. "Since there were no cars in Lucy's time, we suggest that a fall is the mostly likely way that this subset of fractures formed, just as seen in modern patients today under natural conditions."

RELATED: Big-Toothed Prehistoric Human Lived Alongside Lucy

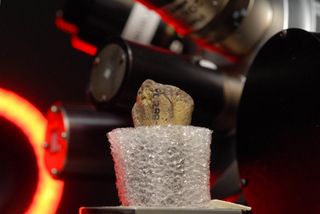

In order to assess Lucy's cause of death, Kappelman and his team studied her remains, which include parts of her skull, hand, axial skeleton, pelvis and foot. The scientists used computed tomographic scans to analyze these parts in detail, and then compared the findings to various documented clinical cases where the cause of death is clearly noted.

In addition to discovering that Lucy's cause of death is consistent with a fall from a high place -- presumed to have been from a tall tree due to where her remains were found in the Afar region of Ethiopia — the fossil clues presented another key piece of evidence.

Fractures in Lucy's upper arms suggest that she stretched out her arms in an attempt to break her fall. This tells us that she was very much alive when she toppled to her demise, and did not die of a heart attack or from some other cause beforehand.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists further found that Lucy died relatively young, but was not a child, since she had all of her adult teeth, including a third molar — a wisdom tooth.

"Her species appears to have grown up faster than us, probably more like a chimpanzee, and I suspect she was maybe 15 years old, so a young adult for her kind," Kappelman said.

Chimpanzees and other modern arboreal primates are far more agile at tree climbing than humans are. They can climb trees from a young age since it's a life or death matter for them.

But even chimps can fall to their death from trees. Famed primatologist Jane Goodall and her team documented 51 such falls in a two-year period, with breaking branches being one of the main reasons that they topple.

Lucy's feet had evolved for better walking on the ground, according to earlier research. This would have compromised her ability to clutch onto tree limbs, probably making falls more common.

Kappelman, however, does not think that this risk caused our primate ancestors to become fully terrestrial.

He said that the arboreal lifestyle "is still a viable niche for lots of animals, including the majority of primates. The first committed terrestrial bipeds (two-legged ground walkers) are probably Homo erectus, but even some modern humans forage in the trees."

He and his colleagues suspect that small-bodied Lucy nested in trees at night to avoid predators, which is what chimps and gorillas do today. This means that, "at a minimum, she climbed up a tree at night, slept there for some hours, and climbed down from that tree in the morning," Kappelman said, adding that she might have sometimes foraged for food in trees too.

RELATED: Photos: Faces of Our Ancestors

Experts contacted by Discovery News were all intrigued by the new study.

Osbjorn Pearson, an associate professor in the University of New Mexico's Department of Anthropology, said, "The evidence was literally right under the noses of many anthropologists for the last three and a half decades," referring to the time since 1982 that researchers have known of Lucy's remains.

Pearson agrees that Lucy probably nested in trees at night to escape predators, and could have foraged in them every so often, especially to get fruits. He thinks her adaptations for walking on the ground likely meant that "A. afarensis would have been more efficient at bipedal walking than chimpanzees, but perhaps less energetically efficient than modern humans."

John Fleagle, a distinguished professor at Stony Brook University's Department of Anatomical Sciences, said that the new research agrees that the fractures on Lucy's "humerus and other bones show the same pattern that doctors see in people who fall from heights and land on their arms."

RELATED: New Tiny-Brained Human Found in South African Cave

Fleagle added that the research "adds a level of detail to our understanding on the life and death of a fossil that is rarely achieved."

William Jungers, a distinguished professor emeritus also from Stony Brook University and a research associate at Association Vahatra in Madagascar, believes that the new paper presents "a provocative but plausible scenario for the demise of Lucy."

Jungers said that "death from accidental falls from trees is surprisingly common in some human groups, like the Aka pygmies, so why not Lucy too?"

Original article on Discovery News.