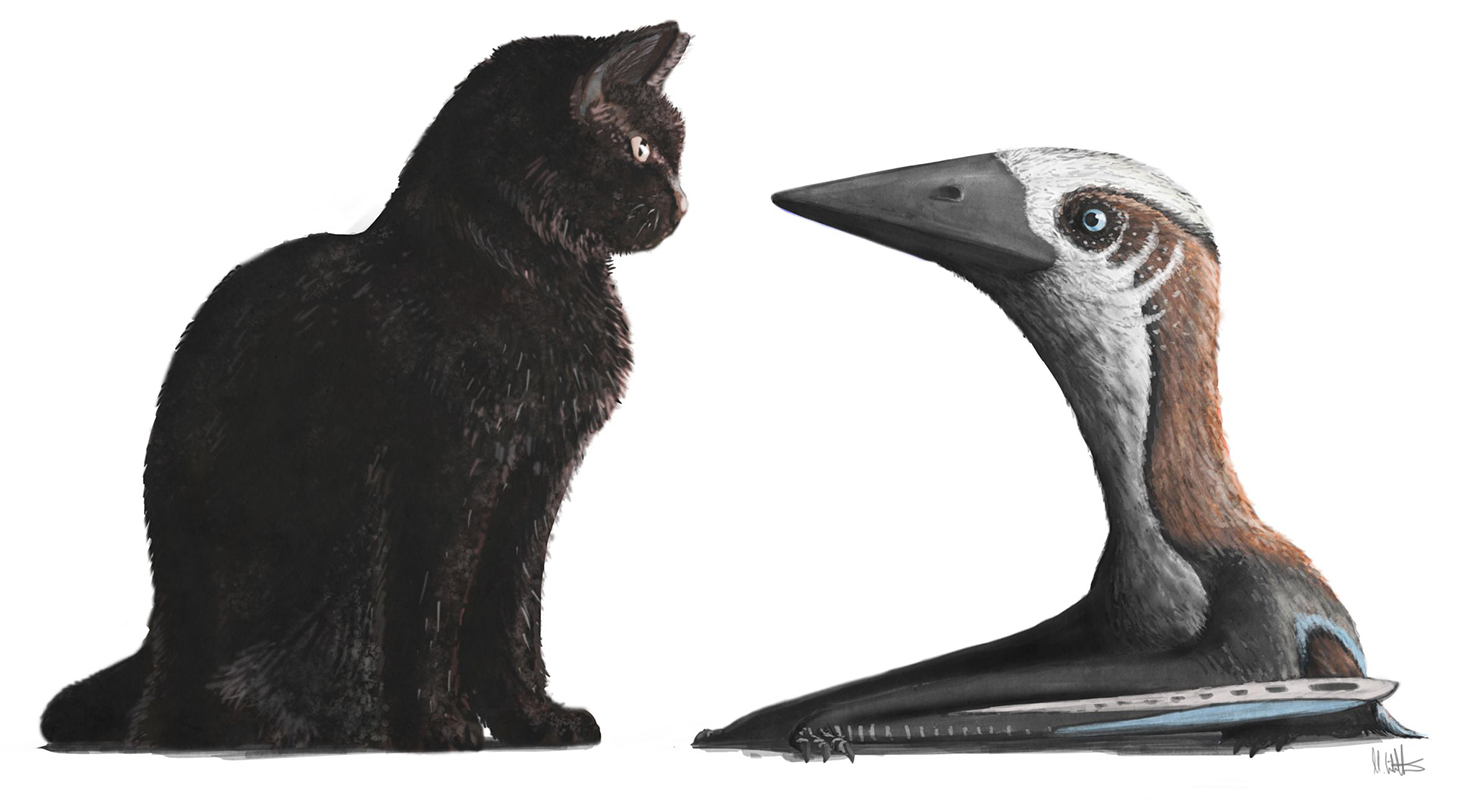

Teensy Pterosaur Was the Size of a House Cat

A recently discovered pterosaur was a real pip-squeak compared to the much larger flying reptiles that flapped across the skies during the age of dinosaurs.

Found in what is now British Columbia, a handful of fossils were described in a new study as belonging to a pterosaur that lived about 77 million years ago, with a wingspan estimated to be 5 feet (1.5 meters) in length. The pterosaur is thought to have been approximately the size of a house cat, measuring 1 foot (30 centimeters) tall at the shoulder, according to the study authors. It is significantly smaller than any other pterosaur from that era, and is the first of its kind found on North America's west coast, the researchers said.

While the new pterosaur has yet to acquire an official scientific name, its fossils provide an important example of the variety in pterosaur forms — especially during the Late Cretaceous, when their diversity was waning, the scientists wrote in the study. [Photos of Pterosaurs: Flight in the Age of Dinosaurs]

Neither dinosaurs nor birds

Pterosaurs lived alongside both dinosaurs and birds, but were neither; they represent a unique reptile lineage that spanned the Late Triassic Period to the end of the Cretaceous Period (about 228 million to 66 million years ago).

The fossils described in the study date to the later part of the Cretaceous and represent only a fraction of the animal's skeleton — a few vertebrae, a wing bone and several other fragments — and were poorly preserved, the researchers reported. Nevertheless, the fossils were still recognizable as belonging to a pterosaur, which has hollow bones distinctively modified for flight, according to the study's lead author, Elizabeth Martin-Silverstone, a doctoral student in paleobiology at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom.

These bones were unusually small for a Late Cretaceous pterosaur, but analysis of their internal structure revealed that the pterosaur was fully grown — or very nearly so, Martin-Silverstone told Live Science. The animal appeared to share traits with a group of toothless, short-winged pterosaurs called azhdarchids that dominated this period, but it was dramatically smaller than any known species, providing the first evidence that small pterosaurs may have lived alongside their much larger Late Cretaceous cousins, the researchers said.

"The general idea is that the end of the Cretaceous had these giant, 10-m [33 feet] wingspan pterosaurs taking over the skies," Martin-Silverstone said. "This reminds us there were other smaller pterosaurs out there, occupying other niches."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"A strange time"

The Late Cretaceous was "a strange time for pterosaur evolution," said study co-author Mark Witton, a paleontologist at the University of Portsmouth in the United Kingdom. During this period, pterosaurs became bigger than ever before, Witton told Live Science.

"It wasn't until the end of the Cretaceous when the biggest pterosaurs emerged, with the longest necks — about 3 m [10 feet] — the biggest wingspans, and body mass [of] probably 250 kilograms [551 lbs.]. Some were as big as giraffes, with wingspans comparable to hang gliders or small planes," Witton explained.

But at the same time, overall pterosaur diversity was greatly reduced from its heyday in the Early Cretaceous, about 146 million years ago, he added.

"That was a point in time where we saw radiation in lots of different pterosaur groups – waders, filter feeders, terrestrial forms picking up food on the ground, dedicated scavengers. The end of the Cretaceous was such a contrast to that, when there were only two or three groups left," Witton said. [Photos: Ancient Pterosaur Eggs & Fossils Uncovered in China]

And as the biggest pterosaurs were evolving, the smallest forms began to disappear from the fossil record.

"It's almost like there was a shift in the average. The whole size range shifted upward, so we started to lose a lot of the smaller ones," Witton told Live Science.

Evolutionary pressures certainly may have driven smaller pterosaurs extinct, but there could be another explanation for why small pterosaurs' fossils from the Late Cretaceous are practically nonexistent, the study authors suggested.

Pterosaurs' hollow bones are known for their fragility — and are scarce as fossils in general — but this is especially true for the smallest specimens, Martin-Silverstone said. It's possible that small pterosaurs were actually more common during the Late Cretaceous than currently suspected, but external factors destroyed their delicate bones before these remains could fossilize. Juveniles of larger pterosaurs certainly existed during the Late Cretaceous, but researchers haven't found any fossils of them either, Witton added.

Ultimately, solving this riddle will require more specimens, which is where overlooked material in museum collections could play a critically important role, the researchers said in the study.

"What we have now — it's not enough to understand this weird phenomenon at the end of the Cretaceous, where there aren't any small pterosaurs," Witton said. "There are so many things in museums that people aren't looking out for. What we want to do is put these things on the radar of researchers and curators, so we can start to build up a good-quality data set of these small specimens."

The findings were published online Aug. 30 in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.